Peter MALONE

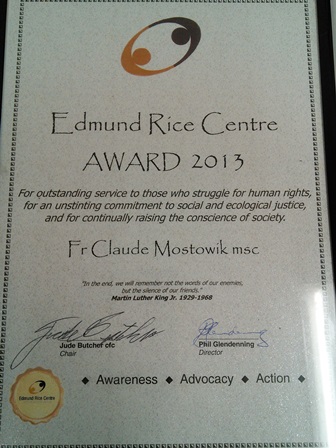

CLAUDE MOSTOWIK, EDMUND RICE AWARD 2013

CLAUDE MOSTOWIK MSC, EDMUND RICE AWARD 2013

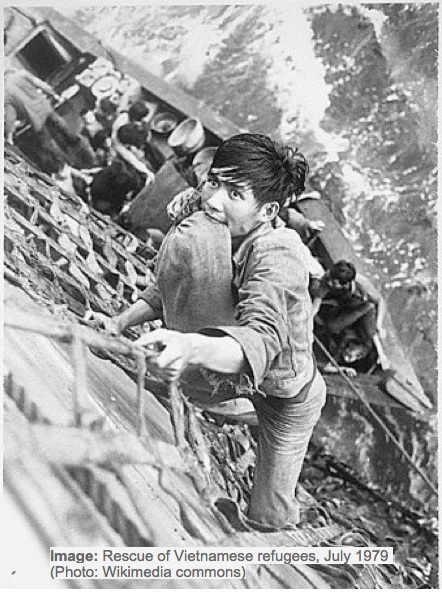

ASYLUM SEEKERS, MALCOLM FYFE MSC

A PLEA FOR A MORE CONSIDERED TREATMENT FOR VIETNAMESE ASYLUM SEEKERS CURRENTLY IN AUSTRALIAN DETENTION CENTRES.

WHAT'S HAPPENING IN VIETNAM – WHY ARE THEY FLEEING?

Many Catholics in Vietnam are being persecuted simply because they practise their faith. Most Vietnamese asylum seekers arriving in Australia now are Catholics, fleeing persecution in Vietnam. About 85% of the Vietnamese detainees in the Darwin Centres are from Nghe An Province, where quite recently there have been abductions and arrests. In this Province (of Central Vietnam) the authorities are especially prejudiced against Catholics. The Bishop of Vinh, one of the dioceses in this Province, the priests and parishioners from My Yen and Con Cuong, both parishes in Diocese of Vinh, have been and are being harassed. There have been beatings, accusations of crimes that they have not done and unjust detentions in jail. Children are prevented from being involved in Christian youth groups. We do know there was a particularly violent crackdown on Catholics in Nghe An Province on September 4. And we are told that on this occasion, it was families and friends back home, of Vietnamese asylum seekers here in Australia that were targeted. Vietnamese priests and Catholics here in Australia are in frequent contact with friends and relatives in Vietnam and are kept abreast of the real life situation there. The widely respected London based weekly "The Tablet" reported on September 14 as follows: "Crackdown on Catholics in Vietnam: Several dozen Catholics were arrested and, according to a local priest, around 40 people were severely wounded, when police and soldiers used grenades, tear gas and batons to disperse a peaceful rally in Nghe An Province on 4 September." (Page 30)

And the facts are well documented. For example, Fides Agency, the Vatican-based information service of the Pontifical Mission Societies, reported on October 9 that 63 Christian pastors and other religious leaders are among those detained in four prison camps in Vietnam. It in turn quoted a report sent by the International Christian Concern (ICC) organization, that the detained face various sentences ranging from 5 - 18 years and are subjected to forced labour for 14 hours a day. The ICC monitors "religious freedom and the plight of Christians in the world."

There is ample documentation that Catholics and other Christians are being singled out and persecuted in Vietnam. In desperation some have sought asylum and risked their lives in coming to Australia by boat. Some have been here for about a year and others arrived after the 13 August. These detainees did not arrived here as tourists nor did they overstay any visa.

Catholics subject to such aggression by government authorities initially seek refuge by leaving the area and staying with relatives in distant parts of the country. In the worst case scenario they try to leave the country. Whole families are affected by the violent attacks of the authorities. They can be publicly smeared on state-run media and accused of obstructing justice simply because they have been vocal in defending their human rights, and their rights to freely practice their faith. They are then accused of leading an uprising because they publicly and vocally challenge the authority, this leads to being accused of treason.

We are hearing examples of Vietnamese Catholics being caught while trying to flee the country, badly beaten and jailed. Earlier this year, a boatload of Vietnamese asylum seekers was caught by the authorities trying to leave the country: all were beaten – two to death, and the rest then imprisoned, where two more died.

What does this say about peoples' fundamental right to seek asylum, be offered protection, in accordance with international law?

WHAT IS HAPPENING TO VIETNAMESE ASYLUM SEEKERS IN AUSTRALIA?

None of the asylum seekers that arrived after August 13, 2013 are allowed to lodge their claim. They are simply "screened out", without even having a chance to explain their situation.

Even more callously, an official delegation from Vietnam, believed to be police or border security officials, were allowed into Australian detention centres to interview Vietnamese people held there. The Vietnamese officials were given access to the asylum seekers' records. The asylum seekers being interviewed were not told who these Vietnamese officials were or why they were here. They were locked in interrogation rooms with young children for up to four hours, some accused of treason, and told they would be sent home. Australian officials have also since told some of them they will be returned to Vietnam against their will, and will be given 72 hours notice prior to deportation. We understand this has happened to about 100 Vietnamese detained at Yongah Hill, and about 15 at Wickham Point .

So these asylum seekers have not been allowed to lodge a claim for asylum. They have effectively been "screened out" without even having a chance to explain their situation. And what enormous ignorance of the harsh repercussions back in Vietnam to families and relatives of detainees here does this show on the part of Australian Authorities that they allow Vietnamese Government agencies to have access to these asylum seekers. Our detainees have been terrified by the mindlessness of this process and by their fear of the flow-on effects back in Vietnam.

Conclusion: We urge the Australian Government and the Department of Immigration to treat Vietnamese Asylum Seekers who have arrived by boat as prima facie genuine refugees in accordance with international law and to process speedily and compassionately their applications to remain in Australia.

Malcolm Fyfe MSC, for the diocese of Darwin.

NELSON MANDELA 1918-2013

Nelson Mandela's story, if told as a novel, would not be deemed possible in real life. Worse, we don't tell such stories in many of our novels.

A violent young rebel is imprisoned for decades but turns that imprisonment into the training he needs. He turns to negotiation, diplomacy, reconciliation. He negotiates free elections, and then wins them. He forestalls any counter-revolution by including former enemies in his victory. He becomes a symbol of the possibility for the sort of radical, lasting change of which violence has proved incapable. He credits the widespread movement in his country and around the world that changed cultures for the better while he was locked away. But millions of people look to the example of his personal interactions and decisions as having prevented a blood bath.

Mandela was a rebel before he had a cause. He was a fighter and a boxer. Archbishop Desmond Tutu says that South Africa benefited greatly from the fact that Mandela did not emerge from prison earlier: 'Had he come out earlier, we would have had the angry, aggressive Madiba. As a result of the experience that he had there, he mellowed. ... Suffering either embitters you or, mercifully, ennobles you. And with Madiba, thankfully for us, the latter happened.'

Mandela emerged able to propose reconciliation because he'd had the time to think it through, because he'd had the experience of overcoming the prisons' brutality, because he'd been safely locked up while others outside were killed or tortured, and also -- critically -- because he had the authority to be heard and respected by those distrustful of nonviolence........

The United States needs that example when speaking with Iran. Colombia needs it as the possibility of peace glimmers in the distance there. Syrian builders of movements and military organizations that fight injustice need that example desperately.

When will we ever learn?

David Swanson Warisacrime.org December5 , 2013

Missionaries of the Sacred Heart from the Irish Province and Daughters of Our Lady of the Sacred Heart worked in South Africa during the apartheid years and the years since, in Cape Town and southern cities, outside Johannesburg, in the township of Ivory Park, and in Pretoria. They began the diocese in the north, then called Louis Trichardt. Australians like Vince Carroll MSC and Sally Duigan FDNSC have worked in South Africa as well.

The Union of Superiors General held its 82nd General Assembly in the Salesianum in Rome

Who we are

Missionaries of the Sacred Heart, an Australian community, in a worldwide religious congregation.

Ministry Mission

Jesus loved with a human heart: with him we proclaim his love to the world.

Peace, Justice, Creation

We work to discover through advocacy, healing and reconciliation, God's presence in our world.

Spirituality

We are to be on earth the heart of God. God has no other heart but ours.

Nelson Mandela's story, if told as a novel, would not be deemed possible in real life. Worse, we don't tell such stories in many of our novels.

A violent young rebel is imprisoned for decades but turns that imprisonment into the training he needs. He turns to negotiation, diplomacy, reconciliation. He negotiates free elections, and then wins them. He forestalls any counter-revolution by including former enemies in his victory. He becomes a symbol of the possibility for the sort of radical, lasting change of which violence has proved incapable. He credits the widespread movement in his country and around the world that changed cultures for the better while he was locked away. But millions of people look to the example of his personal interactions and decisions as having prevented a blood bath.

Mandela was a rebel before he had a cause. He was a fighter and a boxer. Archbishop Desmond Tutu says that South Africa benefited greatly from the fact that Mandela did not emerge from prison earlier: ‘Had he come out earlier, we would have had the angry, aggressive Madiba. As a result of the experience that he had there, he mellowed. ... Suffering either embitters you or, mercifully, ennobles you. And with Madiba, thankfully for us, the latter happened.’

Mandela emerged able to propose reconciliation because he'd had the time to think it through, because he'd had the experience of overcoming the prisons' brutality, because he'd been safely locked up while others outside were killed or tortured, and also -- critically -- because he had the authority to be heard and respected by those distrustful of nonviolence……..

The United States needs that example when speaking with Iran. Colombia needs it as the possibility of peace glimmers in the distance there. Syrian builders of movements and military organizations that fight injustice need that example desperately.

When will we ever learn?

David Swanson Warisacrime.org December5 , 2013

Missionaries of the Sacred Heart from the Irish Province and Daughters of Our Lady of the Sacred Heart worked in South Africa during the apartheid years and the years since, in Cape Town and southern cities, outside Johannesburg, in the township of Ivory Park, and in Pretoria. They began the diocese in the north, then called Louis Trichardt. Australians like Vince Carroll MSC and Sally Duigan FDNSC have worked in South Africa as well.

Frank Fletcher and the Aboriginal Ministry

Great Supporter and Friend of Aboriginal Christianity Father Frank Fletcher MSC

Catholic Communications, Sydney Archdiocese,

21 Nov 2013

Father Frank Fletcher MSC, DTheol

One of the founders of the Archdiocese of Sydney's Aboriginal Catholic Ministry (ACM) and one of the city's most well-known and beloved priests, Fr Frank Fletcher MSC is gravely ill.

The 81-year-old cleric was admitted to Prince of Wales Hospital yesterday and this morning speaking on behalf of the family, his sister Terry Fletcher asked the people of Sydney for their prayers.

"Our brother has been very frail for some months now and he needs our prayers at this time," she told Catholic Communications this morning.

Fr Frank is due to celebrate his 82nd birthday on New Year's Day in just over six weeks' time.

Despite his age, he has just written a ground breaking book which reveals his profound understanding of Aboriginal spirituality and argues that in addition to a more authentic dialogue with Indigenous Christians, there is a need for a sympathetic understanding of the Dreaming which will deepen our own religious experience and help renew modern Christian Theology.

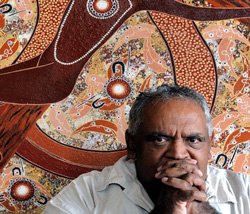

Graeme Mundine says Fr Frank has been an inspiration to Aboriginal people as well as the wider community

"Jesus and the Dreaming: Discovering an Australian Spirituality through Aboriginal-Christian Dialogue," published by St Paul's (rrp $24.95) is currently being printed and should be available within the next few weeks. But already international as well as national orders are being taken via the St Paul website for Fr Frank's book which is a collection of his writings over many years on Aboriginal spirituality and the challenges and possibilities for Western Christianity.

According to Fr Frank's sister, the book is a culmination of her brother's life's work.

"An editor collected his writings and he has been involved with updating these as well as overseeing everything that has gone into the book every step of the way," she says.

Terry is also particularly proud the cover chosen for the book is a reproduction of "The Last Corroboree," a superb painting by acclaimed Aboriginal artist Richard Campbell.

Fr Frank Fletcher honoured by Sydney Aboriginal Catholic Ministry 2013

In February this year, Fr Frank was honoured by the ACM at a special Mass and celebration lunch at the Church of Reconciliation at La Perouse where he was presented with a beautiful print on canvas of The Last Corroboree in recognition of the role he played in the founding of the Aboriginal Ministry and the unstinting support and encouragement he had given over many years.

Graeme Mundine, well known elder and executive officer for the Sydney ACM and Dr Elsie Heiss, another much loved elder and a member of the Wiradjuri nation who worked closely with Fr Frank to establish the ACM which began as a small room in the presbytery of St Mary's in 1988, were among the many who attended the celebration.

At the La Perouse Church of Reconciliation hundreds arrived to thank and pay tribute to Fr Frank.

During the lunch Sydney's Aboriginal Catholic community recalled how he had been asked many years before "Why have an Aboriginal Church?" To which Fr Frank had replied: "The Reconciliation Church is an asset to the community because faith gives strength against difficulties and people of faith are able to take on hard roles. A community needs to have an inner unity."

Artist Richard Campbell who painted the Aboriginal Stations of the Cross...

Graeme Mundine described Fr Frank today as someone who as a theologian had helped raise the thinking and awareness among the wider community about Aboriginal spirituality and its place in Christianity.

At the Church of Reconciliation as well as at St Mary's Erskineville where the ACM holds Mass on alternate Sundays, the liturgy, Lord's Prayer and Mass reflect the Aborginal people's deep spirituality, culture and traditions.

The Mass incorporates specially written Aboriginal prayers and often includes Aboriginal dancers and music such as the didgeridoo. In addition the Aboriginal Rite of Water Blessing and the Aboriginal Rite of Smoking or Fire are frequently included as Penitential Rites.

"Fr Frank has been exemplary in his tireless and unstinting support of the Aboriginal community and has been a good friend over many years. And although there is still a way to go, he has been instrumental in not only helping Aboriginal people discover Christianity but has enabled them to discover Aboriginal Christianity," Graeme says.

Jesus and the Dreaming: Fr Frank Fletcher's book due out later 2013

He explains that before people like Fr Frank, Fr Ted Kennedy and Mum Shirl, few understood that Aboriginal people had difficulty relating to Western Christianity. They had no idea about Northern Hemisphere animals that are used in many of the metaphors in Western Christianity.

"The Spirit of the Rainbow is our symbol of God crossing the entire sky which brings a whole new mindset for the modern Church and recognises the different symbols and concepts that represent God not only to the Aboriginal people but in other non-Western cultures," Graeme says and believes this is shows just how truly global the Catholic Church is.

"We are all Catholic and share Catholic values but the concept and symbols we use for God and the Scriptures may be different depending on our individual history, culture and spirituality across a wide variety of non European cultures."

He strongly believes Fr Frank has helped change perceptions within the Church about Aboriginal spirituality and how this can enrich Western Christianity and the Catholic Church in particular.

"We are all keeping Fr Frank in our prayers at this time," he says.

In addition to his close involvement with Sydney's Indigenous community and the ACM, Fr Frank has also been a long time supporter of St Vincent de Paul Society's Matthew Talbot Homeless Services extending the hand of friendship and providing pastoral and practical care to some of society's most vulnerable and in need.

LOVE YOUR NEIGHBOUR

Love Your Neighbor

Rev. Peter Sawtell Eco-Justice Ministries

A few weeks ago, a newspaper reported asked me a familiar, but always challenging, question. What Bible texts do I look to as a basis for Christian environmentalism? What passages are most important in seeing the need to care for all of God's creation?

Coming up with an answer is both easy and hard. There are so many texts that point us in the right direction and inform our understanding. And there are so few texts that deal directly with the sorts of issues we face in our technological, globalized, and hurting world. What key passages do I want to lift up?

I will confess that part of the way I respond to the question isn't terribly theological. I want a little bit of shock value. I want to give an unexpected answer. I want a few sentences that will make a quotable sound bite.

In this sort on an interview with secular media -- and also when I'm talking to church people for whom eco-justice is a startling new idea -- I want a text that is very familiar, one that is clearly at the heart of Christian faith and ethics. I also want one that will call us into fresh perspectives about our relationships with all of God's creation.

So I pick a text that I'm sure is in every Sunday School curriculum, one that is well-known to every church-goer, and which will be familiar to most who don't go to church. The words come from the Jewish scriptures, and are quoted in the Gospels. In Matthew, for example, Jesus is asked, ‘Teacher, which commandment in the law is the greatest?’ And Jesus answered:

'You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind.' This is the greatest and first commandment. And a second is like it: 'You shall love your neighbor as yourself.' On these two commandments hang all the law and the prophets.

‘Love God, and love your neighbor’ isn't usually thought of as an environmental text. This teaching does have a profound eco-justice meaning, though, as soon as we stretch the definition of ‘neighbor’ into a broad realm.

Such a stretching into a scandalous new area, you might recall, is precisely what Jesus did with the parable of the good Samaritan, when he was hit with the follow-up question of ‘And who is my neighbor?’ As his parable makes clear, loving our neighbor calls us to look beyond our family and friends, and the people who live next door. So, too, a faithful love of neighbors moves us beyond abstract concern or warm feelings, and makes us act with compassion and responsibility.

Using ‘love God, and love your neighbor’ as a central text is fruitful in interviews and conversations, because it then requires the discussion to continue into three essential expansions of our ethical circles of being a neighbor.

- Our neighbors include the whole human family.

We are to be neighbor to the poor and people of color who are the frequent victims of environmental injustice. We are to be neighbor to the residents of Pacific islands and Bangladesh, whose countries are beginning to be inundated by rising sea levels. We are to be neighbor to the indigenous people of the Amazon and Indonesia whose forest homelands are being clearcut, and in Africa where spreading deserts bring famine. We are to be neighbor to the residents of urban areas whose health is degraded by smog, and to agricultural workers who are exposed constantly to dangerous chemicals.

The command to love all of our human neighbors lifts up the justice components of eco-justice. Our compassion and concern are for those who have been hit hardest with painful impacts, and who have had few benefits from these environmental changes. We care for the poor and the powerless, the ones who the least ability to control their situation.

- Our neighbors include future generations.

If we are neighbor to all of Earth's people today, we must also be neighbor to the coming generations who will bear the brunt of today's destructive lifestyle. Because of human actions today, they will be forced to live in a hotter world, a world without thousands of species, a world with more people but diminished resources.

This, too, forces us to see elements of justice. Charity might incline us to leave some resources for those who will come after us. Justice, as a component of profound love, will look at what those future generations have a right to expect from us. Love demands that we provide them with ecological stability and sufficient resources for their ongoing well-being -- which means that we must change our destructive and consumptive ways.

- Our neighbors include the rest of creation.

We must stretch, too, beyond our human neighbors. We are to be neighbor to all the variety of life with whom we share this planet and with whom we relate in ways both dramatic and subtle -- the whales and the coral and the salmon, the wolves and caribou and prairie dogs, the complex communities of life in grasslands and forests and wetlands.

Because God's love encompasses all creatures, the obligations of faithful love also hold us in relationships of compassion, respect and justice with the entire web of life. Now, and into the future, we must care for all the family of life, and for the natural systems which maintain life.

The biblical basis for eco-justice, of caring for creation, is not drawn just from interpretations of Genesis texts: of ‘dominion’, and the Garden of Eden, and the story of Noah. It does not depend on subtleties of Greek meaning in God's love for the cosmos (John 3:16). Those are familiar and true, but we don't need to start there.

The biblical basis for caring for creation is found in the very message that Jesus named as most central, in the two commandments that support all of the law and the prophets. Love God and love neighbor. As our hearts and minds and spirits perceive ever-broadening circles of ‘neighbor,’ eco-justice emerges as an essential, basic expression of our faith.

May God's Spirit move within us to expand our love and vision. May our individual and collective lives be shaped by deep and responsible love of all of our far-flung neighbors.

LITANY OF THANKSGIVING

Litany of Thanksgiving to those who affirm our universal human dignity

Response to each part of the litany can be a simple ‘pray for us’’ or ‘Grant us peace and justice’ One can also add local people in this litany.

Mother Theresa of Calcutta, who worked with the poorest of the poor,

Father Flanagan, who founded Boy’s Town,

Francis of Assisi, who respected all creation and even kissed the leper,

Dorothy Day, who spent her life in Housing of Hospitality,

Francis Xavier, who journeyed all over Asia to share the vision,

Peter Claver, who met the slaves who came to America,

Martin Luther King, who marched for the rights of all,

Rosa Parks, who refused to sit in the back of the bus,

Jean Vanier, who calls people into community,

Those who feed the hungry

Those who shelter the homeless

Those who do the works of mercy

Those who speak out for justice

Those who take time with the elderly

Those who work with children

Those who journey with the disabled

Those who share the vulnerability

Those who listen to others in their need

Those who proclaim equality for all

Center of Concern

NELEN YUBU MISSIOLOGICAL JOURNAL

HyVong - Journey towards Hope

Here are some MSC stories that tell of priests and brothers in action. More stories will be added as they come to hand, so please visit this page again.

HyVong - Journey towards Hope

HyVong - Journey towards Hope

In Bowral in 1980 a small refuge and home called HyVong was formed by Father Strangman, of the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart. It lasted just four years, but it gave 'hope' to almost 50 detached and unattached Cambodian and Vietnamese young men, fleeing Communist reprisals against them after the Vietnam war and the horrors of the Pol Pot years in Cambodia.

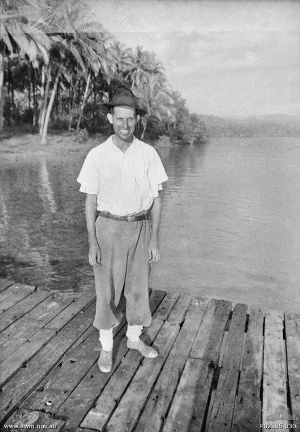

LIFE STORY: Fr TED HARRIS MSC

LIFE STORY: Fr TED HARRIS MSC

What follows is a detailed article by Brian Davies, printed in the Sydney Catholic Weekly, 26th April, 2009. It gives information about the Japanese invasion of Papua New Guinea and the attack on Rabaul and its consequences for expatriates, especially the members of religious orders. The article also contains some biography of Ted Harris. It is published here with the permission of the editor of The Catholic Weekly.

The Japanese occupation of New Britain during World War II led to the greatest single loss of Australian life at sea when a Japanese ship, purportedly taking Australian POWs from Rabaul to Japan, the "Montevideo Maru", was torpedoed by a US submarine. But who and how many were on board the ship? No-one knows – a mystery. What was the fate and where are the remains of the man whose unforgettable heroism saved hundreds of lives, but not his own, the missionary priest, Fr Ted Harris MSC – another mystery. New Year 1941 was a watershed slipping into a tragedy, and was it only a coincidence that it was resolved on Easter Sunday?

Below the slopes of Tavurvur the active volcano, grumbling and frequently darkening the sky over Rabaul with steam and smoke, by April 1941 Australia had assembled a force about 1400-strong to defend the town and the mountainous island of New Britain against almost certain Japanese invasion.

It was possibly the most inadequate taskforce the AIF had mounted and soon to be, so swiftly, perhaps the least successful, although not without its heroes. Yet for more than 30 years after World War II the circumstances of the fall of Rabaul were not widely known, and still aren't.

The defending force comprised the 2/22nd battalion – a militia unit – of the AIF 23rd Brigade, a company of the New Guinea Volunteer Rifles and the 17th anti-tank battery, main weapons – two 6-inch artillery guns. Just before Christmas 1941 they were joined by six RAAF Wirraways, slow old-fashioned trainer planes and certainly no match for Japanese Zeros.

Most European women and children had left by ship or airlift, the last on a final DC-3 flight on December 28 1941, leaving behind about a 1000 Australian traders, teachers and public servants. To this day, their families have asked Australian governments to open wartime files about the decisions that were made then, to no avail. The "received wisdom" is that there are Cabinet documents in Canberra labelled "never to be released". This is the first of the mysteries associated with the fall of Rabaul.

There were as well on the island numerous Christian missions: among them Anglican, Lutheran, Methodist, Salvation Army and Catholic; these last, long-established, were manned by German Sacred Heart fathers, with six mission stations strung from Rabaul in the north to Gasmata, a modest seaport 300km south, as the crow flies, on the east coast. Between the two was an impenetrable mountain range, below which, halfway to Gasmata, was the MSC mission at Mal Mal in Jacquinot Bay, and 75km farther south another one at Awal.

An Irish-Australian Balmain boy, Fr "Ted" Harris MSC was the priest at Mal Mal. He had more than 3000 Melanesian parishioners, a church – St Patrick's, a school, sports ground, a mission store and dispensary – and a two-roomed presbytery backing on to steep jungle.

He was well provisioned, had a launch, a shotgun for shooting game and a gramophone on which he played John McCormack records and other favourites like The Road to Gundagai.

Edward Harris was born in May 1905 in England to an Irish mother and Protestant English father, who converted because he wanted to share his family's passionate practice of Catholicism. They migrated to Australia; Ted learnt that in a family "sacrifice and love are twins". He was a Christian Brothers boy, dux of Balmain CBC's intermediate class 1920 and next year, turning 16, a NSW government junior public servant.

He and a workmate, another ex-Balmain CBC boy Frank Hidden, decided to study to matriculate and do Law. In November 1932, they graduated – Ted with second class honours and a prize in international law. Hidden went on to become a judge. Ted Harris, however, the day after graduation went straight to the Sacred Heart monastery at Douglas Park. He stayed, entered the novitiate in 1933, was professed in 1934 and ordained in 1939. To his vocation he brought spiritual aspirations, a mature mind, a compelling personality he had to tailor to community life and a deep conviction, as he wrote to his sister, that to be a worthy priest his only wish was "not to disappoint Our Lord".

"I came into religion to serve Him, draw closer to Him. If I do that I'll have everything; if I miss, the rest will be worth little," he said.

What else was in Ted Harris' "baggage"? He was a hiker and a bushwalker, Cox's River and the Megalong Valley were favourite spots for camping. He enjoyed sailing, followed boxing and enjoyed a bet at Harold Park on the greyhounds. He once gave his winning ticket to a mate who'd lost and was broke. In most respects he was a typical young Australian whose Irish connection lay in deliberately reproducing his mother's brogue, while he always said and wrote 'Twas and 'Tis and his one expletive exclamation was "Faith!"

But his fervour, his spiritual quest, his journey to God were dedicated and unswerving. Late in 1940, he was sent to the German Sacred Heart missionaries in Rabaul, secretary to Bishop Scharmach MSC. Six months later, the bishop approved his transfer to run St Patrick's mission, Mal Mal. Alone at Mal Mal, he was also teacher, doctor and nurse. It was June 1941.

On January 22, 1942, selected ships from a Japanese fleet of four aircraft carriers, battleships, cruisers and 16 destroyers entered Rabaul Harbour. At 2.30am on January 23 the first wave of 5000 Japanese marines landed. Australian orders of the day were that there would be no withdrawal.

The 2/22nd was a Victorian militia unit – 76 officers and 1400 other ranks – civilian clerks, tradesmen and others "called up" and trained; the battalion band was a Melbourne's Brunswick Salvation Army band*.

The invasion was preceded by three weeks of bombing and strafing. The Wirraways had taken off, shot down two Zeros, but made good their pilots' ultimate "resource" signalling "we who are about to die salute you". All died.

Opposing the landing 26 men died; 60 were wounded. The defence inadequacies were swiftly exposed, convincing the suspicious that "never to be released" Cabinet documents existed. Historian Dr Ian Downs wrote that the destruction of 2/22nd was regarded by government "as a misfortune that had to happen and internment of civilians a matter of course ... (in effect) hide the tragedy and no-one will know".

That day the most final of military action orders was issued: 'Every man for himself.'

Civilians came under brutal control. Fr McCullagh MSC and Br Brennan MSC were taken away and never seen again. Br Huth MSC was beaten near to death with a shovel; 44 other priests and brothers were jammed into the upper floor of a convent building and confined. Native nuns were subjected to ridicule and worse. Native Catholics and other Christian islanders were killed. Bishop Sharmach and his close community were kept under "house arrest". Several hundred men were POWs; more would follow.

Meanwhile, lost to the outside world, the surviving 2/22nd's ordeal began. There was no communication with Australia and hardly any within the island. Fr Harris had no certain idea Rabaul had fallen until the first survivors landed on his doorstep at Mal Mal, a month later.

The survivors hoped to reach Gasmata for a boat or rescue to Port Moresby. To get there however they had to cross the Baining Ranges – 50km of trackless jungle, towering mountains, deep gorges and crocodile-infested rivers – on short rations. In the "wet" it rained almost ceaselessly. Once past Malingi, they would reach the coast.

They would discover Fr Harris at Mal Mal – a figure in old trousers, sandshoes, a white shirt and black priest's hat – as they stumbled towards him. Starting out, rested and cared for, from the Sacred Heart mission at Baining where the ranges began, the crossing had taken nearly three weeks. Like the clothes they wore, they were torn and ripped, too, boots gone, some with sores and ulcers, hungry and exhausted.

Fr Harris cared for them: two hours washing and dressing their wounds, a square meal, sweets and the gramophone playing, some fresh clothes, stretchers to sleep on, breakfast, food packs to take with them, upriver by canoe and then a 50km walk to reach Fr Culhane, an Irish MSC, at Awal.

The next party arrived at Mal Mal with distressing news: A Japanese ship combing the coast for escapers had spotted about 180 men on the beach at Tol plantation in Wide Bay, north of Mal Mal. The men surrendered to a landing party. Their hands were then lashed behind them and each was bayoneted and shot to death. A few survivors were with the escaping party. Fr Harris's coolness and good spirits calmed over-strung nerves and revived morale, but the Japanese were obviously close.

As it left for Awal, this second party advised him that there were probably about another 50 soldiers struggling south.

Happy to leave things to God, Fr Harris resumed life at Mal Mal and its outlying villages, nine and 12km away: medical and nursing rounds, conducting marriages, baptisms, funerals and celebrating Mass at St Patrick's.

The third party to arrive, under Lt Best, estimated there were only 20 stragglers to come. Best was relatively fit and determined to reach Port Moresby. Fr Harris gave him his launch, all his petrol and enough food for the party for three weeks.

No sooner had Best left, than another party walked in, fairly fit. Fr Harris over-nighted them with the usual care and provisioned them for the row upriver to the walking track to Awal. They urged him to escape with them, reminding him of the Tol massacre. He declined.

On the track, moments of perception, of capture and punishment – death ... the stress of flight ... the unforeseeable ... a future as dark as a tomb – a pall along the escape routes, a dreadful companion when the men were at rest. But Fr Ted Harris's cheerfulness would dispel gloom and lift spirits. The next party to reach him,however, brought grim news.

Gasmata was occupied by the Japanese and 200 escapers heading there would soon reach Mal Mal.

With 200 men who now could not go any further, Fr Harris split them into two camps at nearby Drina and Wunung, some of the sick to be cared for at St Patrick's. With a plantation family, the Yenckes, cooking at Wunung and himself catering for Drina, he and the men's officers were running a makeshift army camp. Men were posted to keep watch for the Japanese or, best, a rescue ship. Food was rationed and some of the men were assigned to expand a native garden, but the almost unmanageable problems were malaria, the injured, the sick and the exhausted. Fr Harris was running out of quinine and other medicines. He was to bury nearly 30 of the men at St Patrick's, including, some who claimed to be Catholics so they would receive a Christian burial. He assured the men all could count on that, Catholics or not. A crowded "ecumenical" congregation regularly heard Mass.

The officers – Major Owen, Major Palmer the medical officer, Captain Goodman and Lieutenant David Selby – and Fr Harris established close bonds. Their commitment was to their men, fiercely so, and in Fr Harris they found a man they came to respect and admire. If they were rescued they planned to kidnap him to take him to safety. Waiting, tensions rose. Fr Harris brought the Yenckes and another plantation family in to live in the presbytery. He moved into the school room. Rescue was the only escape.

A slender hope was the possibility that Lt Best might have reached Port Moresby. They weren't to know that Fr Culhane at Awal had also given his launch away for the same purpose. (Fr Culhane MSC was subsequently "tried" and shot dead for helping escapers.)

Good Friday, 1942, fell on April 3. Captain Goodman, a Protestant, went to Fr Harris and said the men wanted him to deliver a Good Friday address, which he did, according to David Selby, a deeply moving one.

Two days later the men were in St Patrick's at Easter Sunday Mass.

The liturgy was interrupted at the back of the church. Two neatly uniformed, heavily armed Australian soldiers called several worshippers out to tell them they were rescued. Lt Best and others had made it. The newcomers had travelled in a launch from Port Moresby to tell them that in three days time the Laurabada would tie up to take them all off.

Gallantry and endurance were needed to get the sick and injured from Drina and Wanung to Mal Mal – some men died doing it; but Fr Harris made one thing clear: he wouldn't be going with them ... he would not leave his parish and his parishioners.

All made their farewells. David Selby later wrote "as we pulled out in a blinding rainstorm he was a spare figure standing on the shore waving, still wearing his smile."

There are conflicting and gruesome versions of where and how Fr Harris died.

It's agreed the Japanese took him away from Mal Mal. The only certainty after that is his execution.

The final mystery in the Fall of Rabaul surrounds the Montevideo Maru. The Japanese claimed that when the ship was torpedoed in 1942 it was carrying all the prisoners of war and civilians taken when they invaded New Britain. But who was on the ship?

The Montevideo Maru Search group says the claim was to conceal war crimes like the Tol murders and massacres at other sites, for which there is evidence, and that there are scores of victims whose last resting places are as unknown as Fr Ted's.

LIFE STORY: FR ROY O'NEILL MSC

LIFE STORY: FR ROY O'NEILL MSC

Catholic Communications, Sydney Archdiocese,12 Nov 2009

Religion is good medicine. Over the past decade, studies have confirmed spirituality and faith have measurable health benefits and not only promote healing after illness or accidents, but increase longevity. In the US, Duke University's Centre for the Study of Religion, Spirituality and Health, scientists have found that people with an active religious life have spiritual resources that can help them break cycles of addiction, recover from depression and spend less time in hospital. According to latest research, patients who are committed to their faith and involved with their religious communities, are not only mentally and frequently physically healthier than their non-believing counterparts, but also have lower blood pressure, fewer deaths from heart disease and other stress related illnesses.

While such findings may come as a surprise to many, for Fr Roy O'Neill, the Catholic Chaplain at Sydney's sprawling hospital's complex at Randwick NSW they are simply confirmation of what he and the Church have long known. Religious belief contributes to physical, emotional and mental well-being, and is a significant factor in promoting healing.

"There is now a stack of evidence from scientists and researchers worldwide on the positive benefits of spiritual and pastoral care. It doesn't matter whether the patient is a card-carrying Catholic or an Anglican, Buddhist, Muslim or from some other religion. If his or her spiritual needs are met, there is a beneficial effect on the protocol of healing," Fr Roy says.

The positive impact of religion on patients is something Fr Roy has seen first-hand during his 10 years as Chaplain at the Randwick Hospital Complex which includes the Prince of Wales Hospital, both public and private, the Royal Hospital for Women, the Sydney Children's Hospital, and the Euroa and Kiloh Centres which provide psychiatric care.

In addition to his work as a Chaplain at the hospitals where Catholic patients number 250 across the Campus on any one day, Fr Roy has written at length about the power of faith and spirituality and their significance in helping patients heal as part of thesis for his Master of Ministry degree, entitled "Moments of Grace and Blessing: Rites and Rituals in the Process of Healing."

Being a Chaplain is an Extraordinary Gift. However, the friendly, down-to-earth, good-humoured, Queenslander, admits that when he was first ordained, he never expected to work in a hospital.

"But while I may not have chosen to become a hospital chaplain, my 10 years at Randwick have been in one sense the most rewarding – a loaded word but I can't think of another word to explain how I feel - and the most touching ministry I have ever been involved with. At times the work can be heartbreaking and is always highly emotionally charged, but against the tragedy and sadness there is the joy of someone making it against all odds or of babies being born and new life created."

Fr Roy also believes a hospital Chaplain is particularly privileged. "It is an extraordinary gift to be invited to be with people at the most sacred moments of life, whether entering or leaving life. It is a wonderfully trusting position to be in - to have people trust you at the happy times of their lives as well as the critical times."

He becomes impatient, however, with the popular misconception that a priests' primary function as a hospital Chaplain is to administer "Last Rites" to the dying. Not only is "Last Rites" a misnomer, a term not so much used now by the Church or Catholics, but a hospital Chaplain's role is far more broad and, as stated earlier, an integral part of the healing process.

At the Randwick Hospital Campus, the Catholic Chaplaincy comprises Fr Roy and Sister Ann Duncan of the Sisters of St Joseph of the Sacred Heart, and is backed up by two parish priests from the nearby Our Lady of the Sacred Heart Church, Randwick who are also part-time chaplains at the Campus and can step in when needed. Priests at the parishes of Rosebery, Coogee and Maroubra Beach are also on call. But the main work is carried out by Fr Roy who celebrates a Mass for staff, patients and families at noon every Wednesday in the hospital complex' small chapel, as well as celebrating a 3 pm Mass there on the first, third and any fifth Sunday each month.

A Chapel for All Faiths

"As well as Sister Ann and myself there are two Anglican Chaplains, a Salvation Army chaplain, a Jewish Rabbi, several Muslim Chaplins, a Presbyterian chaplain, a Uniting Church Chaplain and two Buddhist Chaplains and we all share the chapel," says Fr Roy who dismisses the controversy earlier this year over Crucifixes and other Christian symbols having to be stored between services as nothing more than a "media created beat-up."

"The chapel at Randwick was built six years ago after the previous one in the old P.O.W. huts at the back of the Campus burned down. Both the new and old chapels which date back more than 20 years have always been multi-faith and for the new chapel, all of us from the various different chaplaincies got together to raise the money to have it built."

According to Fr Roy as with the previous chapel, each group of specific religious symbols is kept in cupboards within the chapel and brought out when needed whether it is a Jewish Menora, the Koran and compass showing the direction of Mecca or the Chalice and Crucifixes of the Catholic faith.

Each day after arriving at the Hospitals' Campus around 7.00 am, Fr Roy checks the lists of patients and noting any recent admissions who have nominated themselves as Catholic, and begins his visits of the various wards to speak with new arrivals as well as those who been in hospital for several days, weeks or even months. These visits also include talking with families and one ward he is particularly close to C2West which is the cancer ward at the Sydney Children's Hospital.

Ministering to children battling terminal illnesses might seem grim but for Fr Roy both the children and their families fill him with inspiration and humility. "This is where you meet the human spirit at its most amazing," he says. "The children and their families are just outstanding people and from a spiritual aspect you really do see God's presence in the midst of suffering." He pauses for a moment. "It's hard to put into words but possibly the best way to describe this is to use a slogan that was once for a vocations centre: "God only knows what work a priest does."

He smiles then adds: "One of the nicest things about this work is that often having tried to assist and support people through tragedies or critical times, they frequently contact me later to ask if I'll celebrate a marriage or a baptism or some other joyous family occasions."

Religious Instruction by Correspondence

Growing up on a sugarcane farm in Finch Hatton in Northern Queensland, 73 km west of Mackay, Fr Roy was the youngest of three children by 13 years and grew up with his cousins for playmates rather than siblings. But in a rare occurrence, his cousins were closer than most. His father's younger brother had married his mother's younger sister. "So I had double cousins and they lived next door," he laughs.

His father was Catholic and his mother, formerly a Congregationalist converted to the Catholic faith on marriage. "My parents were religious in the right sense of the word," Fr Roy says. "We went to Mass on Sundays and they were always conscious of the social needs of the community, not just of Catholics but everyone. From them I learned tolerance. Dad was also Chairman of the local council."

But it was his parents' generous giving hearts he remembers most and he treasures the remark from a local who approached him in middle age after his mother had died to tell him how kind she'd been to him, and the meals she had given him as a young cane cutter. "If it hadn't been for your mother, I'd have been in gaol a long time ago," he told Fr Roy.

As a child, Fr Roy attended a tiny primary school in Pinnacle where he received his first-ever formal religious instruction by correspondence with Sister Mary Loyola who was based in Rockhampton. "She was a Sister of Mercy and well ahead of her time, organising religious education by correspondence for kids in State schools along the lines of Distance education," he says. "Our Parish Priest, Fr Hayes from our parish of Francis de Sales was also a major influence on me as a child and I clearly remember him teaching myself and several other sons of cane farmers, the responses to the Latin Mass, sitting under the house of one of our neighbours!"

For his secondary education, Fr Roy became a boarder at Downlands College, Toowoomba, which was run by the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart. "I am not sure how or exactly when I decided my vocation was to be a priest. It was a gradual realisation and probably began in childhood," he says.

Latin a Prerequisite to Train as a Priest

On leaving school, Fr Roy was keen to enter the seminary but first he needed to do senior Latin. "It was 1963 and in those days Latin was a requirement and you couldn't get into a Seminary without it." Finally, Latin and other subjects under his belt, Fr Roy began his training to become a priest with the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart. During his Apostolic year he taught at Monivae College in Hamilton, Victoria and discovered he loved teaching. Ordained on May 24 1975 he returned to West Victoria to teach as the school' senior English master and in 1982 found himself back at his old school, Downlands College, but this time as one of the Senior Boarding Masters. "The kids used to wonder how I knew where to catch them smoking!" he grins.

By 1986, however, Fr Roy finally fulfilled his dream working in an overseas mission at Hagita High School in Milne Bay, Papua New Guinea. But within a short time he was back in Australia and principal of Downland College. His next role was as Vocations Director at the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart in Sydney then in 1997 he took a Sabbatical Year to Ireland before taking up a position in Fiji where the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart were building a Seminary. Then in 2000, he was appointed as Hospital Chaplain at the Randwick Campus.

"What is most important for a hospital chaplain is his compassion and humanity," he says. "Some people who may turn to him for comfort and help may not have been closely associated with the Church for many years and you need to connect with them in a way they feel comfortable. It is very much a ministerial role in a hospital setting and a necessary skill is the ability to just be with people, wherever they may be on their faith journey, and to work out how best to meet their spiritual needs. Doctrine and dogma take a backseat to compassion and understanding."