This program was first broadcast on 27 July, 2008.

Gretchen Miller: Hello, it's good to be with you on Encounter, I'm Gretchen Miller. Today we're celebrating the ordinary lives of a group of men with an extraordinary history.

Khanh Nguyen: Yeah, the storms came around, and the pirates came around, but they didn't do much, they took our boat away and left us on a small island. When I say they didn't do much, because they did not rape the women or kill anyone. We were fortunate in that way.

Gretchen Miller: We'll be meeting a Cambodian and some Vietnamese refugees who came to Australia in the 1970s and 80s under extreme duress, but who now, 30-odd years later, have well and truly settled into the suburbs and communities around Sydney.

Hua Huang: For me and my family, when I first came to Australia, it was like we were reborn again, you know what I mean? And came suddenly to Australia, everything is completely different, different culture, everything, now I'll have to learn from the ground again.

Luke Trinh: My mother, she's a very tough lady, and she pushed me on. She said, 'Why you stop there, you're doing well at TAFE, so go on, get a degree!' So I did part-time for another eight years, so after another eight years I got my degree. I can't stress the importance of the family support.

Gretchen Miller: Whilst most Cambodians are Buddhist, the Vietnamese refugees left a country where ancestor veneration is a part of everyday practice, across a population that is about two thirds Buddhist and the remainder mostly Catholic. Catholicism was introduced in the 16th century but found its strength during the French rule of the late 19th to mid 20th centuries.

Phuoc Vo: When people are down, they always look up to someone to help them and there are quite a number of occasions I did that, I look up to God, just pray to God to help me to get through. But a lot of times you realise that with God you need to put in an effort to get life moving, so you can't really rely on God all the time.

Khanh Nguyen: HyVong gave me hope, you know. Firstly when I came here, only 15 years old, nowhere to go, don't know what I should do next, and it's a base, it's a foundation for me, a stone to step on, and then to move forward.

Gretchen Miller: What binds the men we're hearing from was a home near Bowral then called HyVong, or 'Hope' in Vietnamese. It was set up by the MSC, the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart, and, because of the longstanding presence of Catholicism in Vietnamese society, HyVong provided a welcome sense of the familiar, for Buddhists and Catholics alike. The four years that it ran gave 48 teenagers and young men respite from the all the trauma of the past years. We'll hear from four of these men today, as well as two who helped look after them; Brother Gerard Burke and layman Lee Borradale.

Lee Borradale: I'd been at the Missionary of Sacred Heart Catholic College at Toowoomba and I became Catholic, and then got very engaged in the school and really felt part of a family and a real sense of belonging. And one thing led to another and I applied to become an associate member of that order. So, in doing that, when the HyVong situation came up, it seemed to be a natural extension of wanting to make a commitment to the order that I now belonged to as an associate. I must admit that 'fools rush in where angels fear to tread' is probably apt, because to take over a home with 32 refugee children, it was a pretty big learning curve actually.

Gretchen Miller: What did you know about refugees?

Lee Borradale: I'd had a brother go to Vietnam as a soldier and being a soldier myself (an officer in the reserve) I had a fairly good knowledge of the circumstance in Vietnam itself, albeit from a distance. I certainly had a sense of compassion for anybody that's been through a really difficult time, and to that extent I think I really wanted to do something really worthwhile. We all want to do something with our life that makes meaning, I think.

Hua Huang: Hi, I'm Hua, I'm from Cambodia, and I've been living in Australia for almost 28 years, and I'm self-employed at the moment, I run a café.

Gretchen Miller: When did you start to feel that Australia was home for you?

Hua Huang: I would have to say as soon as I was in Eastwood hostel. I don't know why, yeah.

Gretchen Miller: As soon as you got here?

Hua Huang: Yes, got here. I feel like I'm so happy, you know? Even though back then I didn't know anything about Australia, but I don't know, I'm happy. I've got two boys and a girl and a wife, you know...

Gretchen Miller: Is she Cambodian also?

Hua Huang: Yes, Cambodian, yes.

Gretchen Miller: You met her here?

Hua Huang: Yes, at high school.

Gretchen Miller: Hua Huang had only grade two education before the Khmer Rouge took over Cambodia, enslaving the population and outlawing Buddhism. We'll hear how he survived later, but survive he did, getting to Australia and going straight into high school.

Hua Huang: I went to Casula High School, one year special English, straight to year 10! And then went to Chevalier College, year 11. That was the hardest, you know.

Gretchen Miller: When you went to HyVong, what was that like for you? Because you had already been in Australia for a year. Why did you go to HyVong?

Hua Huang: I think it was my best chance to learn, you know, and learn a lot.

Gretchen Miller: So you studied hard?

Hua Huang: Yes. When I was in HyVong, a lot of people was very helpful and taught me and the boys a lot, yes. I adapted to Australia...I don't know why, because I never had any problem with Australian kids at school or...even until now.

Gretchen Miller: So no racism?

Hua Huang: Sometimes get a few people call you, like, 'ching-chong', but just ignore them because for them they'd never met Southeast Asian people. Ignore and be friendly with them and later on...it means a lot, you know.

Gretchen Miller: How long had it been since we'd had a significant influx of refugees?

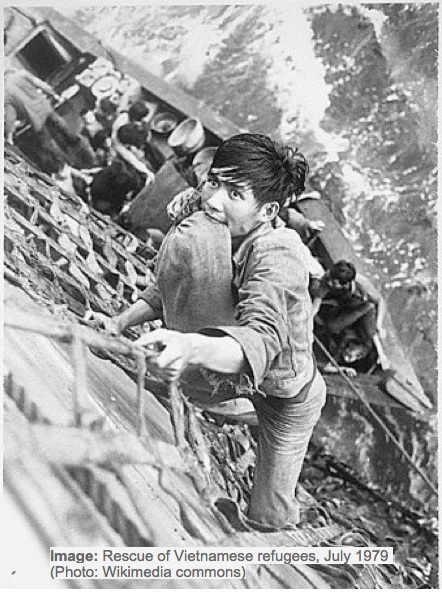

Claudia Tazreiter: It was really the post war period, post WWII period, where we'd seen a large influx of what we might call unpredictable migration, flows of migration that hadn't been planned. For a country like Australia which really is built on migration, but migration that's planned by the government, refugee movements come as a little bit of a surprise and a shock to the Australian public often. And certainly that first movement of Vietnamese to Australia by boats was a shock. It had been some decades since refugee flows had come.

Gretchen Miller: Dr Claudia Tazreiter is a senior lecturer in sociology at the University of NSW, with a focus on forced migration.

Claudia Tazreiter: That particular period in Australian history saw some significant changes, particularly to do with how we view newcomers, how we view groups of immigrants. So what we'd seen in the early 70s is a shift in policy from one of assimilation of migrants to one of multiculturalism under the then Whitlam government. And that continued under the Fraser government as well, that approach.

There is though of course a difference between policy and social attitudes in the general public, and social attitudes towards newcomers take a much longer time to change. There had always been historically antipathy towards certain groups of migrants in Australia, which was really fostered and accelerated by the White Australia Policy, which was the assimilationist policy. And the environment that these young Vietnamese men came to in Australia at that period in the late 70s and early 80s is one where the social attitude reflected a great deal of antipathy towards newcomers, particularly Asian migrants.

The Vietnamese at that period were very small in number in the Australian community, in the hundreds, so they would have felt quite strange in the Australian public sphere. They would have been noticed walking around and in everyday life, in ways that today perhaps we can think of African refugees who have come to Australia in more recent years being noticed because they're small in number and still seen as very culturally different and so on. So the Vietnamese would have similarly felt strangers.

Luke Trinh: My Vietnamese name is Trinh Hu Duc, but since I start at HyVong I picked the name Luke because it makes it easier for people to call me, and I don't like being called Duc, so it rhymes so that's fine. Actually it's nearly 30 years since I came to Australia.

Gretchen Miller: When did you first feel that you were at home in Australia?

Luke Trinh: To me, it's something that's very hard. Sometimes when you're in a certain situation, you will feel that you're not at home as such. But no, I quite feel at ease being in Australia most of the time.

Gretchen Miller: Now you're married and you have two children. When did you meet your wife?

Luke Trinh: By chance that I met one of my schoolmates. We met at the petrol station and he was filling his car, we start talking and he says he's going to get married, so he invite me to his wedding. So that's when I met my wife. She came all the way from France because she left Vietnam and she went to France to join her family there.

Gretchen Miller: How old were you when you got to HyVong?

Luke Trinh: Possibly 18 or 19 years old.

Gretchen Miller: How did you find it? How did you end up there?

Luke Trinh: Just merely by chance because of my Vietnamese friends, they are Catholics and they just happened to tell me that one of their friends is going to this special group, got sponsored by a priest, and at that time I found that a very interesting idea, so I joined

But myself, I'm not Catholic, I'm Buddhist, but yes, I found it's a very positive experience. It's helped me in broadening my perspective in life. Basically, to me, my character has been shaped up by family from the start, my parents, especially my mother. She always taught me to respect people, be nice to people, don't do harm to others which you don't want to happen to yourself. With that principle, it's applied to any situation, any religion, regardless whether it's Buddhism or Catholic or Muslim.

Gretchen Miller: The Vietnamese communists did not discriminate towards particular religions. In 1975 when they took over the Republic of Vietnam, Catholics and Buddhists alike lost temples, land and money, and their priests, nuns and monks were sent to re-education camps.

When the Cambodian and Vietnamese refugees started coming to Australia in 1976, there was little in the way of government services to help them settle. The White Australia Policy had only just been scrapped. The Liberal Fraser government had opened Australian doors to refugees and by 1981 the concept of multiculturalism was an integral part of government, if not yet accepted by the general public.

But after such a long period of outright rejection there was little institutional know-how to help the new arrivals. Whether unauthorised, or entering under the Community Refugee Settlement Scheme, the refugees went to a migrant hostel for a few weeks to find their feet, or stayed with other refugees, not knowing what to do and where to go.

That was when the church and community groups stepped in, providing access to education, health, accommodation and language services. But they too were inexperienced at dealing with trauma.

Gerard Burke: I'd be up there in the dorms at night-time and the screams and the dreams they were having were just outstanding, they were just awful.

Gretchen Miller: Brother Gerard Burke was in charge of HyVong during 1980.

Gerard Burke: I didn't really go into their lives that much, I suppose I didn't feel comfortable in asking them. I suppose they offered each other company. They had their own selves together and they had their own dedication and work ethic, quite extraordinary really, and they tried very hard. I suppose you wonder how they survived through this really. Their communication wasn't that good and you think of the trauma they'd been through and we really didn't know how to handle this trauma.

Gretchen Miller: So you found their distress very distressing.

Gerard Burke: Very distressing, yes, very distressing. I suppose I didn't know how to...I didn't go to counselling myself, I think I should have gone to debriefing or whatever, you know? But I didn't. The only thing I did was to be there with them, I suppose, and accept them as they were. I mean, they weren't all saints, we had a few difficulties with them. I mean, I didn't know what to do at times.

Gretchen Miller: This is Encounter, on ABC Radio National, and we're talking about the lives of some Vietnamese and Cambodian former refugees after they met at HyVong, a Missionaries of the Sacred Heart hostel and school in Bowral in the 1980s, and of the impact their arrival had on Australia's refugee and foreign policy in the years since.

The governor of NSW, Her Excellency Professor Marie Bashir, did substantial psychiatric work with Vietnamese youth in the early 1980s. She speaks of the role the churches played in supporting these children.

Marie Bashir: I think their role was very, very precious because what they demonstrated was compassion and unconditional support.

Gretchen Miller: But they had no expertise, did they, so they were flying blind. That must have been difficult.

Marie Bashir: Yes, but the most important thing within a human being is acceptance of another, unconditional acceptance and respect and, if you like, where children are concerned, love too. That's often unspoken, that's non-verbal, and these young people would have picked that up.

Some of them from the south may have been Catholic too. Well, the Christians from the north relocated to the south during the civil war, so it wasn't a very bizarre experience. There was a strong church element in Vietnam in particular. It wasn't as if...'who are these strange people?' There would have been a familiarity even if they'd been non-Christian.

Gretchen Miller: Tell me about Father Brian Strangman who began HyVong. What sort of a figure was he for you?

Phuoc Vo: He was a very kind man, his face said it all. His voice and tone when he speak to you is very calm and very stress-free.

Gretchen Miller: Phuoc Vo is a pharmacist, with a business in Hornsby and another in Cabramatta. He's married, with two children, and he left Vietnam when he was just 11 years old. At 13 the young Catholic boy used to observe the founder of HyVong, Father Strangman, talking with the older boys.

Phuoc Vo: I remember that he used to come around at night-time, talk to the boys because some of the boys, they had a lot of worries. Their families need help, but they also have to study or they're expected to work to help their family at home, and a lot of them had speak to Father, and so I can see that Father always come and comfort them, give them a very positive conversation. That help us a lot because I think when you come to Australia you probably don't know anybody that will do that, and here you've got a priest here who speaks English but you probably understand about 60% or 70% of his speech, but at least his gesture and his kindness on his face is really comforting.

Claudia Tazreiter: Churches did play a big role in the period from the mid 70s to the 80s when this group of Vietnamese boatpeople arrived. At that stage they were really breaching the gap, so they saw a deficit in services that were available to those young people, and also in that period saw it as their pastoral role to offer assistance. But of course they don't necessarily have the training and the know-how, and dealing with people from situations of violence who've often seen terrible things done to their families and their close friends and their village and their community does require particular training. And in more recent periods there's been a growing awareness of that.

It's interesting though because what we've seen is government take up the slack after that early period where churches were delivering some of these services to the Vietnamese refugees. In the period following that, the government at the time assisted in developing these services and often provided services. And there was an accumulation of knowledge which was gained over a period time, for instance, in various government departments.

In more recent periods, as with other services generally in the Australian community, it's been devolved again to the community sector. Again we're seeing patterns similar to the period of the mid 70s and 80s where well-meaning groups and organisations may receive funding but don't always actually have the awareness and the training to do these things as effectively. So, again, it's a more ad hoc approach. Some of the services that are provided by the church organisations for asylum seekers...in particular, the Sisters of Mercy run an asylum seeker centre and have done for many years and do an excellent job.

Gretchen Miller: A focus, even obsession with education as a way to break with the past and look to the future is recognised as a common characteristic amongst young refugees from any background. In fact, the tougher the past circumstances, the more determined to study they become. The HyVong boys in the 1980s were no exception. Luke Trinh was there for three years.

Luke Trinh: My parents, they sacrificed a lot for me and my sister to escape, so it's my duty to better myself so they can be proud and say it's worthwhile for their sacrifice. But at that stage I was setting my target not very high, because when I started at HyVong I at least thought, okay, maybe I could do...the best is the school certificate rather than the high school certificate, so I set myself something practical that I think I can achieve.

Then the Sisters at the convent they persuaded me to follow on, do year 11 and 12. So I was very reluctant because I say, 'How can I do that because it's so difficult,' you know, the language barriers and the education system. But in the end I follow through. But what happened is that when I finished at HyVong and I came down to Sydney to further my study and find employment, and I was lucky enough to have a traineeship with Telecom back then and yes, I excel. I graduate with distinction from TAFE. This is something I'm pretty proud of.

Gretchen Miller: Your parents must have been very proud. Were they okay?

Luke Trinh: Yes, yes, they joined us about five years later.

Gretchen Miller: So they must have been very proud of you.

Luke Trinh: Yes, but my mother, she's a very tough lady, and she pushed me on. She said, 'Why you stop there, you're doing well at TAFE, so go on, get a degree!' So, again, I did part-time for another eight years, so after another eight years I got my degree.

Gretchen Miller: Fantastic, that's wonderful.

Luke Trinh: But the thing is, I can't stress the importance of the family support.

Lee Borradale: The Vietnamese boys, as I said to my students yesterday, I would have to go into the study at night and say...at one o'clock in the morning, 'Go to bed,' and they would say, 'Mr Lee, we have not finished our homework. How you do this?' And I would say, 'You have to go to bed. Out!' And away they'd go. The next morning I'd wake up and look down from my flat and look down into the study and the lights are on and they're back in there early to try to finish their work.

Another instance that really stands out for me because it's one I often talk to Australian kids about now, is going down into the study at night and seeing a boy going through a book and going off to my office and sitting down and working and coming back and see him still going through the same book, almost in tears. And he says, 'Mr Lee, what's this word? I cannot find this word anywhere.' And I said, 'Have you been looking for that all this time?' He said yes. I said, 'What word?' And he points and the word is 'twas'. I said, 'What are you reading?' And he was enrolled in a year 11 class and they were doing Shakespeare. I hit the roof. I was really appalled. Fancy a kid coming out of Vietnam and not having a modified program. But that's just one example of a lot of pressures.

Gretchen Miller: Phuoc Vo says he was a daydreamer at school, but even so he made it into pharmacy, and he's still driven to learn.

Phuoc Vo: I just take part-time to do a course called Infection and Immunity offered by Sydney University and hopefully I'll do a bit of research for life after pharmacy.

Gretchen Miller: Are you hoping to do some work back in Vietnam?

Phuoc Vo: Well, that is a dream but my wish is to get my hand on research. With the career that I have at the moment I'll have enough financial backup so later on I'll be able to go back to Vietnam, start my own private, no-pressure research, along the line of leprosy or tuberculosis, and hopefully we can come up with something that will help the general public. I'm taking part in this program because I thought that this an opportunity for me to get on the national radio to say thank you to the Australian public, the people that have put up a lot with us. And the community in Bowral; without their help, without their generosity I wouldn't be a chemist in Hornsby like I am here today. I would like them to know that I will never, ever forget their help and their generosity.

Khanh Nguyen: My name is Khanh Nguyen and I'm working in a company called EDS, and I'm in the IT area.

Gretchen Miller: And you studied your HSC for two or three years?

Khanh Nguyen: Three years. I started in year 10, into year 11 and year 12, yes.

Gretchen Miller: Did you have any English when you came to Australia?

Khanh Nguyen: None at all.

Gretchen Miller: Okay, so you came, you studied for two and a half years, your HSC, and you got such a good mark you were able to go into IT.

Khanh Nguyen: Yes. It was hard, struggling, long nights, no weekends. I guess that everybody can do it, just put their mind and heart into it, that's all they need.

Gretchen Miller: Have you seen much change in Australia and Australians in the 25 years that you've been here?

Khanh Nguyen: I think Australians have become more tolerant, I can see that change, compared to 20 years ago, yes.

Gretchen Miller: Even during the John Howard government when there was Pauline Hanson and a kind of expression of anxiety and fear about refugees?

Khanh Nguyen: Well, they come and go. I believe that in Australian society there's still a lot of good people around who accept people all around the world and who has no hatred for anyone from outside of Australia, for no reason.

Gretchen Miller: Have you been back to Vietnam?

Khanh Nguyen: No. I would love to one day, yes. Basically it's the government who run the country there, I just don't agree with them, a lot of things. I left the country because of them, so...I don't know, maybe I'm too harsh to them. I've been to a lot of blogs on the internet and have argued with them about communism and what it is to believe that communism is the best thing for them. They run the country like a capitalism country but they claim themselves as communist. It doesn't make sense at all. It has improved a lot economically, not politically in a sense; there's still not much freedom around in religion and speech and human rights. Not like Australia where you can say whatever you like.

Gretchen Miller: So you enjoy that, being able to say what you like?

Khanh Nguyen: Oh yes, yes, freedom.

Gretchen Miller: Now, Dr Claudia Tazreiter points out that since the arrival of the Vietnamese refugees Australia has developed a reputation for its counselling of sufferers of torture and trauma. Those who have access to these services through the resettlement program have a much better chance in the long term of integrating in the community. For unauthorised arrivals it remains a different picture. Detention has a powerful and negative impact on ongoing psychology, even after release.

Back in the early days of refugee services, Professor Marie Bashir, now best known as Governor of NSW, worked as a psychiatrist with Indochinese children like those from HyVong.

Marie Bashir: Reports were coming in from school counsellors (this is in the public schools) that although the children were well behaved and not complaining about anything, it was noted that they got a lot of psychologically based symptoms; headaches, tummy aches, and sometimes would have to leave class to go to the sickbay. And the other thing that was noticed was that in their artwork, when they were given free time to do drawings, the most tragic drawings emerged of pirates boarding these little shaky ships they were on, with daggers, and some bodies being thrown overboard. So what we saw in these drawings, which the sensitive teachers were collecting, was that these children were bottling up lots and lots of traumatic experiences, things that they probably didn't even have the language to describe.

Gretchen Miller: When you worked with them, given that they didn't have the language, how did you approach it? And given there wasn't much of a...we hadn't done that kind of work before.

Marie Bashir: We brought them in on weekends and during the school holidays. So they could still attend school full-time, which of course was their strength. So we let them talk about these things. They felt ashamed that they'd been through a war. They didn't know how to explain why their country was selected to be bombed, to be poisoned et cetera, so it must have been something bad there. We were able to get them to, I guess, understand and accept that wars had gone on over the centuries and that in fact their families and their people were good people.

Gretchen Miller: So, shame was one of the major unifying emotions?

Marie Bashir: Yes, it was. We were very surprised to find that, that they were absorbing a sense of guilt.

Gretchen Miller: Through the latter years of the Labor Keating government and accelerating during the Liberal Howard government, Australia's immigration policy has focused on 'skilled migration'. It wasn't always so. The Fraser government of the mid 1970s, in the wake of White Australia, was strongly humanitarian, pro-Asia and, as the Vietnamese refugees began to arrive in Australia, pro family reunion.

For Phuoc Vo, this was particularly poignant. As an 11-year-old boy he did not get to farewell his mother at all, getting on a boat by accident when only his three older brothers were meant to go.

Phuoc Vo: When my brothers planned the trip to escape out of Vietnam, that night that we escaped there's a lot of people come from the city, come and stay in my house to re-familiarise themselves with how to get to the shore and the boats to go. I happen to host a group of four or five young people my age. Basically during the day I'd take them to the market, I'd take them to the old movies, we'd go and play soccer, just like any other kids do. So on the night that we escape out of Vietnam, because we used to sleep together on the floor, they got up at midnight and I said to them, 'Where are you going?' And they said, 'I'm going home.' I said, 'Can I come?' because my house is in the countryside, so their house is in the city and I love to go to the city. So they said, 'Yeah, if you want to, you can come.'

So we packed up and go, and I just didn't have anything with me. We walked for about 1km then I realised that we're just going the wrong way, we're supposed to go to the bus stop, so anyway I knew that there was something wrong, but you can't go back now. So I just had to keep quiet and follow them.

Gretchen Miller: Why couldn't you go back?

Phuoc Vo: Because if I happen to return back then the whole authority is going to know that there is someone here trying to make an escape.

Gretchen Miller: Did you get to say goodbye to your mum?

Phuoc Vo: No, I think Mum was sleeping.

Gretchen Miller: So you got on that boat...you must have felt like just running, but you had to get on the boat, because the grownups were putting you all on the boat, is that right? And it was quiet, dead of night...

Phuoc Vo: Yes, dead of night, quiet, nobody allowed to say anything. Everyone just got bundled onto the little boat, and we were waiting for another group to turn up, and then the captain started the engine and we left. But at that stage I was throw up with the seasick, and just don't want to do anything and don't want to know anything anyway.

Gretchen Miller: You were just too sick to care.

Phuoc Vo: Yes.

Gretchen Miller: Where did you get to? Was it Malaysia or Thailand you arrived at?

Phuoc Vo: We ended up in Palau Bidong, it's one of the islands in Malaysia. When my brother saw me on the boat on land they just stared at me, I wouldn't dare say anything back to him. But two or three days later when the seasickness subdued then I start regain my conscious and looked at everybody, then I knew that I've lost something really important, that was my mother. I think the first day, when I see other friends of mine that I entertaining while in Vietnam and allowed me to come on the trip, now I looked at them and they all had their mother with them. And even though their mother shouting at them, but they are still a lot better off than I am, I've got nobody, I don't have my mother and from now I realised I don't know when I will ever be seeing my mother again. That was a very terrible feeling. I remember that I lie on the bed and tears came out of my eyes, and normally I don't cry, boys don't cry, you know? But that was a very, very hard feeling, like the very emptiness in you that you know is going to be here forever.

Gretchen Miller: And were you able to communicate with your mother once you...I'm not sure how long you were in camp for.

Phuoc Vo: I think we were there roughly a year until we come to Australia. Then I actually make official contact with my parents in Vietnam by writing to them, when I was at HyVong.

Gretchen Miller: So a couple of years later.

Phuoc Vo: Yes.

Gretchen Miller: Despite being both the Fraser and Hawke governments' official policy, family reunion was complicated for Vietnamese children. Lee Borradale.

Lee Borradale: They get to the Philippines, they get to Palau Bidong in Malaysia, they get to Sancobasi in Indonesia, and then they languish. Because being teenage boys, if a freedom country takes them on it's much more difficult and expensive to look after them. So, when they were sponsoring, when countries were taking people out of the camps, they would take whole families, so the boys quickly learnt that it was better to claim somebody as their uncle, attach them, even change their name, change their date of birth and get to Australia. And when they got here there was, at that time, 2,000 refugee children that weren't with their parents.

Gretchen Miller: But the children no longer had their paperwork in their original family name, as happened to Kahn Lam, who took up with a family called Jung in a camp in Malaysia.

Lee Borradale: So now he's Hal Jung, not Kahn Lam. He comes with the family to Australia, they're a good family, but Father Strangman takes on Hal at HyVong, and he proved to be a real leader and a person of integrity. But the boys were trying to sponsor their families that were still in Vietnam because the government came up with the idea of the Orderly Departure Program. Rather than have Vietnamese escaping by boats and dying at sea and the pirates and all the rest of it, they could control the inflow if they had a tap that they could turn on or off. People could apply to come and be sponsored by their children. But here's Hal, goes to the department, gets the papers, fills it out, and he gets a letter saying 'You can't sponsor Mr Lam because your name is Mr Jung'. Of course we then took up, along with a few other people in Australia, asking the government to give the boys an amnesty and correct all the personal details. And that eventually happened, and I feel really good about that.

Gretchen Miller: Did you have to change your name to get here, or your age to join...?

Luke Trinh: Oh yes. At that stage, back in Vietnam, the government had the policy of letting the Chinese ethnic people to leave the country in exchange for their wealth. Yes! So you're supposed to leave your possessions and you're allowed to go free. So my mother, she bribed people to get the false birth certificate for me and my sister. So what she did was sold the house into gold, most of it she exchanged that gold for the false documentation for me and my sister. So imagine if you had to do that for your family. She had to rent back the house that we used to own.

Gretchen Miller: Very hard. I'm sorry.

Luke Trinh: It was like sardines lying in the boat. I went through...we have two attempts to get out because the first attempt the boat was about some 100-odd people, and it was the stormy season. We boarded this boat in the dark. They kept as quiet as possible, they don't want everyone to know these people can go, but still the boat was full, crammed, and it's not more than 20 metres, as I recall. So it was stormy and we nearly sank, so the boat returned. And then they shore up the sides of the boat.

Do you know what happened? The second attempt, what happened was that the police that took bribe, they let more people on, saying 'yes, your boat is now better so you can take more people'. So in the end it nearly doubled the amount of passengers, and we sail out, and we got the police escort at night. We had three attempts to land, and we were pushed out and we were pulled out, and at one stage the Malaysian or Thailand police, they hung the captain.

Gretchen Miller: Hung?

Luke Trinh: Yes, hung him with a rope, tried to extract some money. And at another stage we got close to land and we got shellfire across the bow several times. Another day we came to a fishing village and we got rocks thrown at us and people got injured, blood everywhere. So it is not easygoing, I can tell you.

Gretchen Miller: Luke Trinh's mother bought her son a false ethnic Chinese birth certificate, which made it easier for Luke to leave than as a Vietnamese national. His mother kept her other son behind, just in case. It's estimated half the Vietnamese boatpeople lost their lives at sea. Luke made it to a camp in Malaysia and was accepted to immigrate to Australia. His parents and brother joined him some five years later.

The refugee influx resulting from the Pol Pot dictatorship in Cambodia was felt soon after in Australia. It marked the beginnings of another change in Australian policy. By 1990, Cambodian asylum seekers were no longer allowed to live in the community and were instead held in mandatory detention centres.

Cambodian Hua Huang's long journey to Australia took six years, during which he lost almost his entire family. It began in 1975 when the Khmer Rouge invaded Phnom Penh and the city was cleared out, the people marched to villages in the countryside.

Hua Huang: All the adult males, they killed them all. My father was the last one. I still remember clearly, after we had lunch and I was walking along the rice field, just follow my father, and then this man came in and asked my father to go away for a few days. I knew something wrong, and my father wanted to pack a few clothing. He said, 'There's no need to.' And that's it, and they never came back.

Gretchen Miller: What did you do? Because you were only little, I think.

Hua Huang: Back then, just never felt any scared or worried at all. And I was the oldest boy in that village.

Gretchen Miller: How old were you?

Hua Huang: I think about 13 or 14, something, but back then because of the starvation, because back then you work all day, you had no food and probably no nutrition, and you never grow.

Gretchen Miller: But you had to get away, I think, from there.

Hua Huang: You can't escape anywhere. If you go to the next village, people will recognise you, you are from other village. You never think of tomorrow, just think of the next meal. It's hard to explain. Back then you live in that village, you only knew what happened in that village at all, not even the next village, you knew nothing about them. Sometimes you heard rumours only, but not until we were free by the Vietnamese then we find out what happened in Pol Pot regime. They killed people without reason at all, even until now they don't know what happened.

Gretchen Miller: Hua's mother went silent before she died of starvation and grief at the loss of much of her family. The young malnourished boy had to bury his mother in the hard ground, but barely had the strength to dig. He covered her body with thorns, to keep the wild animals away. But he did survive and when the Vietnamese invaded Cambodia, he was sent to a refugee camp in Thailand.

In a sense he was one of the 'lucky' ones. Later Cambodian arrivals were the first to experience the new Australian detention centres, where asylum seekers were held until they were confirmed as refugees, a policy that has lasted to the present day.

Claudia Tazreiter: It started really in 1989, the policy was firmed up in '92 and applied to the Cambodians. Many people argued that that also had a particular foreign policy implication because the Labor government was heavily involved in the peace process in Cambodia, and when you're involved in that sort of international relations foreign policy arena brokering a peace deal, if you receive refugees from that conflict it sends a particular sort of signal. And many people argue that that is one of the reasons why detention of this particular group of Cambodians began, and then of course we saw it applied to all unauthorised arrivals, and in a way that's very particular to Australia; non-reviewable, of women and children as well. That's since been softened, but a very harsh policy compared to all other nation states in fact.

Gretchen Miller: HyVong lasted just four years, but in that time aided 48 refugee children. Towards the end, health problems beset its supporters in the MSC, including Lee Borradale. The program moved briefly to Sydney to be closer to refugee communities, but a governmental shift in emphasis from large to smaller foster homes, coupled with a lack of ongoing funding, led to HyVong's closure, yet its impact is still felt today in the lives of those for whom it cared. As one of the many small cogs in early refugee services, it played its part in Australia's coming of age in the Australasian region.

Marie Bashir: I think in fact probably the aftermath of the Vietnam war contributed enormously to Australia's maturation as a nation, in its awareness that it did belong in Asia, its awareness, which is now reaching a crescendo, that Australia has an enormously influential role to play for good, for the common good, at the highest level of diplomacy, in terms of security, but also in making the lot of our neighbours much better than ever before. And working hand in hand with the great and more powerful Asian nations, not only China but South Korea and Japan, to ensure a stable Asia Pacific region.

Gretchen Miller: And you could say these boatpeople were the beginning of that.

Marie Bashir: I think so actually. Looking back now, that was the turning point, it raised the consciousness of people across Australia, whatever their background. There's no doubt about it in my mind; that was the turning point for Australia.

Gretchen Miller: Her Excellency, the Governor of NSW, Professor Marie Bashir. We also heard from Lee Borradale and Brother Gerard Burke, former managers of HyVong, Dr Claudia Tazreiter, senior lecturer in sociology at UNSW, and of course Khan Ngyuen, Phuoc Vo, Hua Huang and Luke Trinh, and many thanks to these men for sharing their lives and stories. You can hear extended interviews with Phuoc Vo, Lee Borradale and Marie Bashir at our website. The program today was mixed by Judy Rapley and I'm Gretchen Miller. Thanks for your company on Encounter.

Hua Huang: All the parents would tell us, look forward to the future. Or, whatever has happened has happened, the place in Australia is the best place for you, for your future, so make the most out of it.