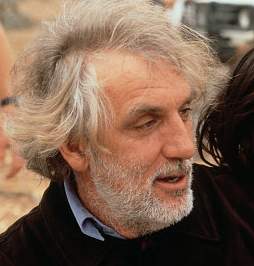

PHILLIP NOYCE

Clear and Present Danger is a Tom Clancy action thriller but it seems to be an ethical film or a film that takes ethical stances?

Yes, it has a very strong moral line. It's really about the rule of the law - one of the basic assumptions of the film is that human beings are imperfect and, as a result, we need protection from ourselves. That's why we codify human behaviour by erecting laws, by having moral codes that we are expected to follow. This is a film essentially about what happens when we don't follow those laws.

That's what America was doing in the '80s?

It's what the whole world has been doing. It's about the chaos that results when we ignore the laws or the moral code.

This is a film for the new political era. In the post-Cold war world, the influence of the American president has become even greater as the United States is increasingly called upon to act as a police force to the world. This is a film that asks when it is appropriate for such a powerful nation to act and how should it act. Jack Ryan has to decide whether he keeps quiet and not injure the presidency, the institution he has served for so many years or does he do something that will endanger his own career and reputation and endanger the presidency and plunge the whole country into turmoil akin to Watergate or the Iran Contra affair.

Staying with ethical issues, what do you think Backroads contributed to an Australian understanding of aboriginal issues?

I don't think it contributed a whole lot to understanding. I think it probably contributed much more to aboriginal self-awareness because, as insignificant as this might seem, it was the first film which gave them a hero or an anti-hero. And the film has been very popular - even now, 20 years later, it's still screened and shown all around Australia to aboriginal groups.

I'm not sure that it had a great effect on the rest of Australia because essentially it was preaching to the semi-converted. I don't know whether it made them any more aware.

You're pleased with it in retrospect?

I think so. I mean it was principally an artistic exercise, and part of that notion turned it into a political tract. The idea was to construct a B-movie, a road movie, and then, by inviting Gary Foley - who was a known activist and spokesperson for the then strong black movement in Australia, an emerging black movement - by inviting him to be the star, I knew that there would be a political confrontation in the making of the film and that this would appear on the screen. But that was an artistic decision and, as it turned out, the film then evolved into a political statement.

So I'm pleased with it in retrospect in as much as we achieved that confrontation. We captured it on screen so the film was a weird combination of this escapist B-movie and political tract, and somehow they sat together in the one strange document.

There are more explicitly religious themes in Newsfront. In looking at, say, the presentation of the Catholic Church in films, Newsfront offers

some significant perspectives: Angela Punch McGregor's staunch character, especially, her leaving her husband and, against the laws

of the Church, actually re-marrying and giving the Church away. There were also church sequences associated with the anti-Communist

referendum of 1951. What was your perspective on things Catholic as you dramatised them in Newsfront?

You must remember that this is not exclusively my perspective because Bob Ellis was the writer of the original piece - I adapted the screenplay but he was the original screenplay writer - so he's principally the author in that respect or it's a shared authorship in film terms, because I was then interpreting his writing and, in a sense, adapting and reinterpreting it by the characterisations and so on.

I think that Australia and the Australian character has been formed through the confrontation between Irish Catholicism and Anglicanism and, of course, these are, at least in part, seemingly irreconcilable philosophies. In my interpretation, the one philosophy, the Irish Catholic philosophy born out of the combination of the Irish experience and Catholic doctrine, is that you should not expect to inherit the earth while you're on the earth but you will later, whereas English and Scottish Protestantism says you will inherit it now and you should do everything you can to get it because it's yours. So take it and don't worry about later. We'll worry about that when we get there.

This is a film, in part, about the confrontation of those two sets of values. But it's also very much a film about Australian Catholicism, the good and the bad aspects of Australian Catholicism - the repressive aspects and the enlightening aspects. But, as we know, and as in America, the Catholic Church was also seemingly split into two extremes: one the extreme Right, the other the extreme Left. And it has always harboured these seemingly irreconcilable philosophies.

Angela Punch Mc Gregor's character, in moving from her staunch stances to her abandonment of Catholicism, seems to represent what was

actually happening with Catholics during the 50s and 60s?

Yes, the film principally describes change, and Australia has changed enormously since the Second World War. The seeds of those changes are to be found in that first decade after the war.

In Heatwave we again find ethical issues. You have used the word `confrontation' several times. Heatwave seems to be an ethical-confrontational film.

Yes. Heatwave was the story of a working-class Protestant boy who made good. I don't know whether audiences realised that, but we had always assumed that he was a working-class Protestant and that Judy Davis's character was a middle-class Catholic girl. She, in the Catholic saintly tradition, had adopted a social cause - had set herself up as the spokesperson and protector of the working class. He, as a working-class boy, of course, was now forced to confront the moral implications of his own success and how that affected other people.

In a way, the religious and ethnic backgrounds of the two characters were just a continuation of the conflicts that we had seen in Newsfront, but Australia had by this stage moved from a principally working-class and upper-class society to a principally middle-class society.

That's captured in the atmosphere of inner Sydney, its buildings and the regulations of law and government.

Obviously it's a film which deals with ethics and morals and responsibilities and just like Clear and Present Danger, the issue of right and wrong. But it seems as though so much Australian history - and I'm talking about that conflict between Irish Catholicism and English Anglicanism - was captured in those conflicts over land development. By that time, of course, it had been embraced by groups who had come to Australia after World War Two. The English seemed to have joined with any nouveau riche who presented themselves, whether they were Czechoslovakian or Hungarian or whatever.

The most interesting thing about Australia is Irish Catholicism - I mean, it's the basis of the country.

Interestingly enough, I think that it is the basis of the value system and has had much more effect - or at least it has produced the unique Australian character - much more than the English, in my opinion, simply because of its strength.

Through personalities and the public moral stances?

A great deal of that has to do with transportation, as Robert Hughes points out, as much as it does immigration. This is because of the number of radicals, whether they were political or religious or social, who were transported from the British Isles between 1788 and 1850. As Hughes points out, every single radical movement in the British Isles sent a representative to Australia.

You moved into Asia with Shadows of the Peacock (Echoes of Paradise).

Echoes of Paradise was a very different film from the one we intended to shoot, because the film was meant to be set in Bali and, at the last minute, due to an inflammatory anti-Suharto family article in the Sydney Morning Herald, all permission was withdrawn and we ended up shooting a bastardised version of the film in Thailand which we probably would have been better off not to have shot.

It might have been much more political?

Yes, the original story was very different. It was really about the Balinese character's alienation and his coming to terms with it, coming to terms with a western influence and his traditional obligations, trying to work it all out. Wendy Hughes' character went through a very similar journey in the original story. It's just that the setting and the Balinese character were very different once we moved to Thailand.

Twice in Clear and Present Danger there were references to East Timor - briefly in a news bulletin on the radio and in a remark made to the

American President by one of his advisers.

You did hear it? Actually it's not the radio, it's the TV earlier on - in fact, it prophesies a revolution. It's a little low, unfortunately. I mixed it too low, but in it the Fretilin have taken over the radio station in Dili.

It was a bit low but then the President's or his adviser says that the situation is calm.

I put it in for the Indonesians. It's symbolic really. I thought, `We'll put it in and we'll see if they pick it up. If they don't, well, that's one over them because they'll have this film out there throughout the country, a hundred prints all around Indonesia and a lot of people will hear it, will wonder about it and they will start some discussion. If they ban the film, then it will be really interesting, because they'll ban it on such a flimsy pretext. This itself will cause some discussion. Otherwise they'll have this sixth column element running around all the villages of Indonesia.

But I should have mixed the TV comments - it was a delicate thing - where the Fretilin have taken over the radio station, just a little louder. I was afraid that if I made it too loud, the authorities would hear it and they would definitely cut it out. But I now realise that it's just a little low.

It's in there for the Indonesians. It's aimed squarely at a building in Djakarta called the Department of Information, which is full of funny little men who do nothing else but listen to radio shows, television shows, read newspapers and things like this, so that they can ban whatever is considered anti-Indonesian. It's a whole building of Orwellian characters.

And your move to Hollywood?

I grew up watching and delighting in Hollywood movies. Hollywood is the Mecca for directors and I'm happy to work there while I can. I am interested in the content of a film rather than its pictorial possibilities. But I am also an outsider and can bring a `South Pacific cynicism' to a film and that is a virtue. With Clear and Present Danger, there is an opening close up on the American flag. I can force the audience to look at the kitsch and reflect on it. It is a portrait of American life slightly different from one made by an American, an involuntary filter placed over events. Czech Milos Forman's view of American life is different - and the U.S. liked it. Paul Verhoeven, with Basic Instinct, brought a combination of repression and indulgence that is Dutch. With the Jack Ryan stories, I have a combination of escapism and reality (though some believe one cancels out the other) and audiences can be entertained and enlightened simultaneously, escapism and political relevance all rolled into one. That's the best combination.

As a director?

There are ten or fifteen superstars in the United States on whom Hollywood depends. But there are three to four hundred directors waiting for a phone call from the superstar!

The director is a ringmaster in a circus. A good circus is no good without a good ringmaster. All those good acts can fail - a big pause and someone needs to bring on the clowns, and when the clowns aren't funny, you need a drum roll. The tightrope walker beings. And you need another drum roll.

But directors are also like vampires sucking the life-blood ideas out of everyone around them - and then calling them their own. A director needs to have a soft front, a strong back and allow everyone to speak up.

Interview: 8th September 1994