Guatamala, Quiche, E.J.Cuskelly perspective.

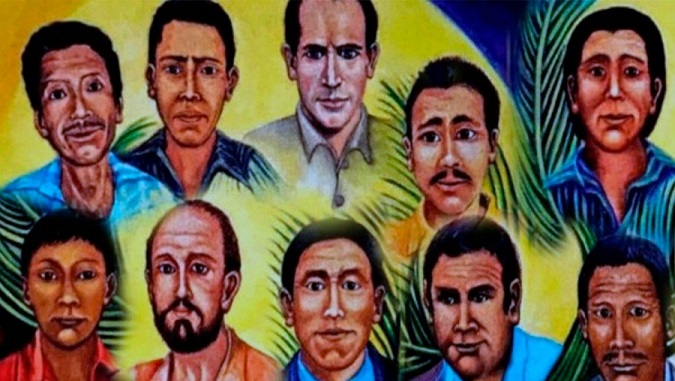

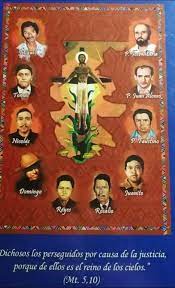

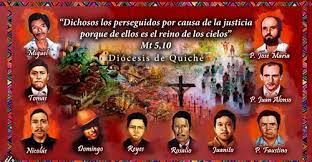

June 4th, first time celebrating the new feast of the beatified martyrs.

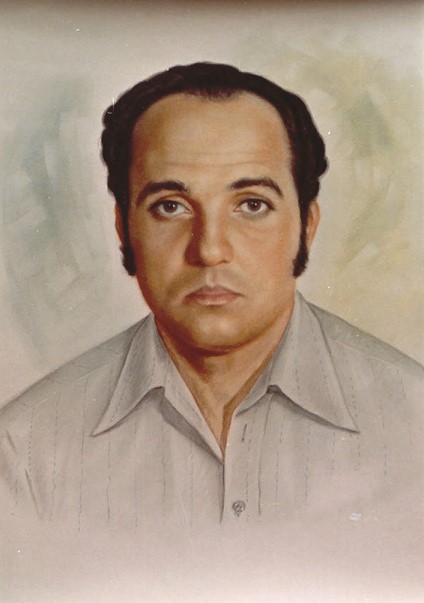

Jose Maria Gran MSC

For those visitors who would like some reading, below is an excerpt from a talk by E. J. Cuskelly MSC about his experience while Superior General about visiting Guatamala and experiencing its history and MSC missionaries there. It throws light on the Spanish colonisation of Central America and the consequences. (It is also an insight into Jim Cuskelly himself and his perspective as Superior General.) With thanks to Tony Arthur MSC for text and photos.

Let me pass now to Guatemala in Central America, where many MSC have lived and worked and some have died a violent death. Guatemala is a delight to the eye and the ear. The place-names ring like bells run wild: Chichicastenango, Sacapoulas, Chimaltenango. There, in the highlands, the air is clear as crystal, the colours of the Indian costumes are as brilliant as birds of paradise, and the sun sets in a glory that is as warm as the smile of God.

In January 1980, in this strikingly beautiful land, I met with a group of MSC missionaries, my friends and brother priests. On the shores of Lake Atitlan framed majestically by its three volcanoes, we talked of the coming murder of at least three of their number. We knew that a brutal military government had placed their names on its hit-list. In Australia, we find it hard to imagine the brutality that exists as an everyday reality in other lands. However, though hard for some to believe, it is easy to understand. Those of you who have seen the film “Romero” would have some idea of the situation in many Latin American countries.

The Spanish conquistadors invaded Guatemala in 1522. They had horses; they had guns. The Indians had neither and were easily defeated. The Spaniards took for themselves (and their descendants) all the more fertile lands. They made their own laws about land-registration. Their descendants prospered. Some of them became very rich with plantations of coffee, sugar, bananas and other tropical fruits. The Indians were driven back into the hills. They knew nothing about land-laws. Deprived of their former lands, they set up their little farms on the hillsides. There they grew their corn and their peppers. They ran a few cattle, pigs and chickens and eked out an existence right on the poverty line. There was a way for them to earn a few extra dollars and to clothe their families. They could go down to the coast to work on the farms and plantations of the rich. There they earned less than a dollar a day - about $5 a week (I’m speaking of the 1970s). Australians would earn between three and four hundred dollars a week for the same work. Most of their $5 a week would be paid back to the rich to buy food and clothes. The rich land-owners owned most of the shops as well.

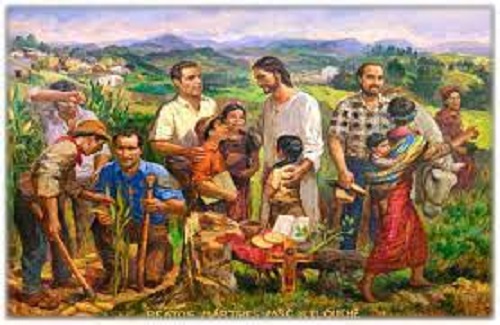

Some years ago, MSC missionaries came from Spain to work among the Indians who had been Christians of sorts ever since the days of the conquistadors. The missionaries ministered to their spiritual needs. They also taught them better farming methods; they imported superior quality cattle, helped them to form their own cooperatives and to set up their own shops. The missionaries also talked about social justice and the concept of a just wage.

Missionaries with the People

The rich families felt threatened. If they had to pay just wages, if they lost their cheap labour, they would lose a lot of their wealth. They paid the military to force the Indians to work for them, to destroy their cooperatives and even to shoot their leaders. The next step was for the ‘big-wigs’ in the military to decide that, if they were to do the dirty work for the rich, they should have some share of the riches. The army took over the government. Then retiring generals and colonels also took over tracts of land where the Indians were living. Invoking the old land laws, they claimed legal justification for this robbery. If the Indians resisted, they were shot.

Then the missionaries spoke out. They were not political men, but they were friends of the Indian people. They had the courage to insist that the human dignity of the Indians should be respected, that they had basic human rights: they had a right to a just wage; they had no obligation to work for the rich plantation owners - they had a right to the lands which the military officers were stealing from them. It was a crime to rape their wives and daughters; it was a crime to shoot their young men.

This proclamation of the Gospel did not please the rich and powerful. The rich resented losing cheap slave labour. The military resented losing a chance to get rich at the expense of the Indians. All of them feared that the priests would make public the atrocities which the soldiers were committing with the backing of the rich.

Jesus and the Martyrs

During those days in January 1980, on the shores of Lake Atitlan, surrounded by the beauties of God’s creation, we MSC discussed the ugly deeds wrought by evil men. All of us were afraid. Some were afraid that they would be the ones to die; the rest of us feared that soon we would have to bury our dead. We asked whether it would not be best for those on the hit-list to leave the country while there was still time.

Someone said to me later: “There’s an easy solution. You are their superior; just order them to leave.” Like many easy solutions, this was no solution at all. I was sure that the missionaries would not feel bound by any such order. They believed that it was their duty to stay with their people, in spite of the danger to themselves. Furthermore there are two ways of destroying a missionary. One way is to assassinate him while he is carrying out his duties for his people. The other way is to have him appear to desert both his duty and his people. The second is, in its own way, a type of death, and, for the dedicated missionary, it is worse than the first. They stayed with their people and I went my way.

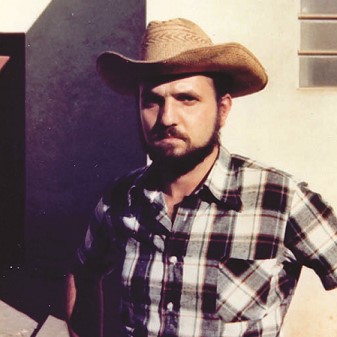

Jose Maria Gran

During the next few months I heard of the death of three of our priests. Firstly we learned that José Maria Gran had been killed, and in Barcelona I shared in his parents’ grieving. Then Faustino Villanueva was assassinated and later Juan Alonso. All three were the most pastoral and least political of men. Eventually, the Bishop declared the Diocese closed and ordered all priests and nuns to leave. It was then that the other MSC also left. Later some went back underground; we believe that at least one of them is dead.

Funeral, Jose Maria Gran

You will wonder: But how can people get away with such injustice? They get away with it, firstly, by being very careful about interviews permitted to foreigners. Secondly, they have developed their own philosophy of “The national security as the greatest good”. In this philosophy anything is justified if it protects “national security”. All that is opposed to it is a crime. It is sedition to criticise officials; it is a crime to oppose the government. It is a crime to oppose the military even when they are stealing your lands. This sort of philosophy justifies all kinds of violence perpetrated by the government. And sadly, President Reagan and others believed that all opposition to a government in power was leftist or Marxist. Nobody asked: how did these people come to government? Do they govern justly? In Latin America many governments came to power by violence; and they govern by cruelty and greed. But - I am wandering from my central theme.

Like all religious orders, we MSC have a book of Constitutions which describes our ideals and our way of life. The second Vatican Council asked all religious to examine their Constitutions and bring them up to date. The old M.S.C. Constitutions contain the words: “Following the example of Jesus, we will strive to lead others to God with kindness and gentleness. Trusting in God’s grace, we will be ready, if necessary, to lay down our lives for them.” During the 1970s, there were some who thought that this was romantic stuff, beautiful but unreal. It should be omitted, they said. But in 1981 when we met in Rome to finalise the rewriting of our Constitutions, we thought of Jose Maria, of Faustino and Juan Alonso. We listened to this letter from the Church in Guatemala which read: “Your priests saw the Indians going hungry; they witnessed the suffering of the peasant families. They brought the light and strength of the Gospel to stop the enemies of God from spreading death through our land. This was their crime: to preach to all people their right to live with dignity.” Then we took up our pens and we re-wrote with pride: “We will be ready, if necessary, to lay down our lives for our people.”

Guatemala will be forever a part of my life. The Indians still suffer in that beautiful violent land. In spite of the sacrifices made, their world has not been re-born. We who knew them will live with the memory of our martyred brothers - especially when we hear songs like these: “Empty chairs at empty tables where my friends will meet no more. My friends, my friends, don’t ask me what your sacrifice was for.” (Les Miserables)