Christmas greetings and blessings for our visitors.

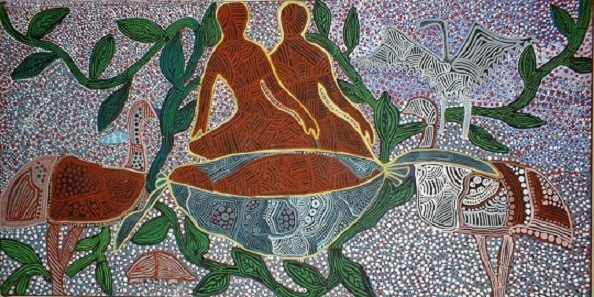

A Bethlehem painting by Suzanne Nurra.

A reflection (excerpt from Andy Hamilton SJ, Eureka Street)

The images and language of Christmas have grown particularly weary. As it has become a public rather than a religious celebration, the words associated with it have been commodified to sell food and drink, all kinds of trinkets as presents, and a generalised bonhomie as the appropriate mood. Even the cards that put Christ back into Christmas make the manger a nice place, remove the dirt and smells that go with cattle, shepherds, camel travellers and two young people seeking shelter after a long journey. For people who do it hard, the language, the gift-giving and the feasting cannot but remind them of their exclusion.

If we want to renew religious language and images we must begin with attention to the words we currently use, noticing their resonance as well as their meaning. It is then important for the language of prayer and reflection to be grounded in deep contemporary experience.

In the Christmas stories, for example, we need to pay attention to the experience of people who have a similar position in our society — to find equivalents to the young people desperate for a room in which decently to bear a child, to the shepherds regarded as marginal and irreligious by a religious society, to Herod’s soldiers free to intimidate, to rob and to kill, and to a grotty field on the edge of town.

In prayer, too, we need to find words that encompass the desperation, rage, terror and passion that need healing and acceptance. Finally, if our words are to open to us another world beyond that of our daily routine, they must be evocative, finding intimations of immortality in the mortality that they touch.