A Tiwi Islands, MSC, culture story, John Fallon MSC. Part 2, Pukumani Ceremonies condemned or accepted

Creative Accommodation?

These histories of conversion by creative accommodation of Christianity are becoming so common as to be a new orthodoxy. And it could be said that this global pattern included the efforts of missionary priests on the Tiwi Islands who, in the wake of the Second Vatican Council, turned to the Pukumani ceremony to "inculturate" the faith for the Tiwi. Looking at the missionary archive alone might give historians such an impression.

But after meeting the Tiwi, my concern is of the potential of the "creative accommodation" model of Indigenous conversions to overshadow Aboriginal people's own conceptions of their histories, imposing non-Indigenous categories on Indigenous experiences. In speaking with Tiwi people, I hope to understand Indigenous histories on their own terms, not through the lens of their colonisers, and to view Aboriginal peoples as full historical agents, not merely as reactors or resistors to Europeans.

And "mutual conversion" is not how the Tiwi tell their history of Christianity, nor do they emphasise creative incorporation of a new faith into their culture. Instead, according to Tiwi people, they have long been Catholic. Tiwi narratives of conversion insist that the Church did not perceive their faith until the intervention of their spirits. Their spirits ruptured the priest's understanding when, in a moment of crisis, Fallon turned to Tiwi ritual knowledge for safety, calling to the Tiwi elders for help. In this moment, the Tiwi elders ministered to the wayward Fallon. They modelled Christian virtues to the priest who learns to confess, do penance and convert to Tiwi culture.

Whereas priests were proud of their progressiveness to reach Indigenous souls, Tiwi interpretations disrupt and overturn this vision of inculturation. For them, priests' attempts to accommodate them was, in fact, appropriate submission to their elders and spirits. As another Tiwi woman told me, "if you want someone to follow your religion, you've gotta come to them."

Reconciling Pukumani

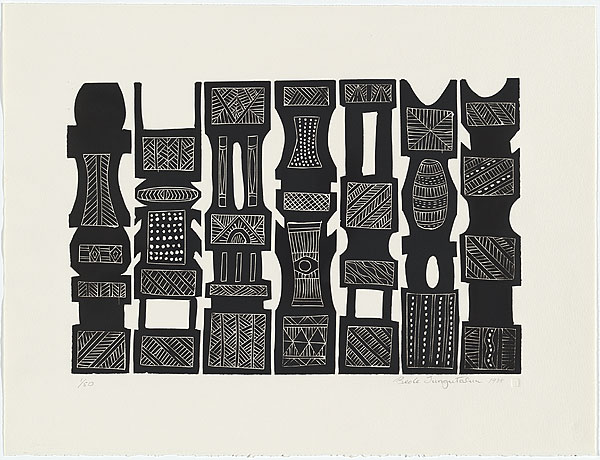

Tiwi culture is known for the Pukumani poles: unique grave posts central in Tiwi mortuary rituals. When someone dies, they become a mobuditi. Mobuditis are so light they can walk on water. They linger where the person once lived or where their body lies. They can be dangerous: if lonely or upset, they might kill. Tiwi people practice elaborate rites to assist the mobuditi. These are also incredible displays of Tiwi art, dance and music - including the Pukumani poles.

Pukumani also refers to the complex of ritual mourning, given to the Tiwi by their creator-ancestor, Purrukapali. On the death of Purrukapali's son, his rival, the Moon-Man (Tjaparra), offered to bring the boy back to life on the third day (just as the moon reappears every month). Purrukapali refused, declaring "you must all follow me; as I die, so you all must die." He carried the child's body into the water, where he joined his son in death. Purrukapli's choice means all Tiwi must follow Purrukapali; all will die.

As the mission consolidated its presence in the first half of the twentieth century, it took harsher measures against "pagan" elements of Tiwi culture. Old people tell me they resented being forbidden from visiting the "pagans" - that is, their relatives who camped nearby. They also resent they were not allowed to attend ceremony as children.

The missionary concern was not arbitrary; Pukumani could have disturbing meanings when translated into their own theological understandings. When, by the late 1960s, Tiwi people recounted the story using Christian terminology - saying, "we shall all follow [Purrukapali] all of us down into hell" - it is likely missionaries understood the Pukumani ceremony as a rejection of the Christian heaven.

The missionaries drew connections between Christ's resurrection and the Pukamuni ceremony. When offered the hope of resurrection, Purrukapali stubbornly refused: he seemed an archetypal pagan. For Catholic priests, Purrukapali's role in Tiwi cosmology must be that of Adam or, perhaps worse, Satan himself. A ceremony following Purrukapali's command, seemingly damning all Tiwi to death or even hell, was deeply disturbing and spiritually dangerous.

So how did the Pukumani and Catholic church reconcile? Barry Puruntatameri was one among many who retold the pivotal event:

"Some Tiwi, Tiwi was working with the missionary. And he saw the big mob. He look in the bushes here ... and it was on Sunday. Sunday was big ceremony, biggest ceremony they had: Pukumani. This Tiwi guy, he went down and he said, 'Oh, I gotta go tell the priest'. He went down and he saw the father. He said, 'Father there is big ceremony, Pukumani in the bush'.

"And he said, 'Where?'

"'In the bushes' ...

"Everyone was dancing, clapping, everyone dancing. Few of those men saw it, you know, was coming. He just walked gently, but they didn't see him. And he was right behind them, watching. Next thing they saw and he just bolted through here. They all just ran out in the bush, they went and left the ceremony. He went and threw that Pukumani, he knocked it down, Pukumani pole.

"And after that, after that, he went across to Melville and he had an outboard motor, he was going to make mass to the other community, on Milikapiti. Anyway, that boat engine came out. It went under the water. That was punishment for that."

As he went on his rampage, the old people cautioned Fallon that he was making a mistake. Some had been forewarned in a dream: Father

"Those old people said to him, 'something got to be happen to you' and he came across by boat and he try start that engine then he run right in the middle of the water to stop. That engine stopped."

The old people sat on the shore, waiting for Fallon to call for help. Though the priest had wronged them, they were not angry because he knew not what he did:

"He came and shook the cemetery pole. The old people weren't angry, they weren't. They were sitting with spears and fighting club, but they knew it was because the mission didn't understand."

The mobuditi, disturbed by the priest's toppling of the poles, was "cheeky," sabotaging the outboard motor (remember, moboditis can walk on water). Another storyteller told me how the boat began to sink, the priest nearly drowned, "that's when he called out for help. 'Help! Help!'" before Tiwi people rescued him.

The story is reminiscent of St. Peter's attempt to walk on water. Fallon had no faith in Tiwi culture, so he sank down, saved only when he turned to the Tiwi. But the story is also reminiscent of Purrukapali himself. Not realising he was in the danger from the angered mobuditi, Fallon was inadvertently following Purrukapali to a watery grave. When Fallon turned and accepted Tiwi help, he experienced a resurrection like that the Moon-man offered, choosing to follow a better way.

The story continues: the offending priest saw his error and repented. "After that, maybe six months later, one year later he apologises." Using the genre of Christian conversion stories, but applying these to the priest and the Church, Tiwi people demonstrated in their story telling their Christian understanding. In a role-reversal, the Tiwi people pronounced forgiveness on the repentant priest:

"He said sorry to our older people. He went back, the next day he went back. 'Sorry, sorry, but I know', you know, 'God gave you your culture and like Christian way'."

Tiwi people remember teaching the priest the meaning of ceremony and about the truths of the spiritual world. Not only did the priest repent of his actions but was "converted" to Tiwi tradition:

"They brought him back here to Bathurst [Island] and they explain to him. 'What you did back there was wrong. You shook the poles and knocked the pole over. That's why the spirit got you. What we did back there, we wasn't worshipping evil, we were having ceremony for a deceased person, a family member. That's why when you shook the poles and you got in the middle, the spirit got you.' That motor went underwater, the bung went missing. That's when he believed in our culture."

The priest's error was not mere disrespect, but failing to understand that this Pukumani ceremony was, for Tiwi people, not pagan but a Catholic ceremony. Fallon had said "you all pagan mob," but he was mistaken. Tiwi people had a broader vision of what could be authentically Catholic:

"He just knocked all the ceremony poles. It was very wrong because that's the culture ... I don't know why, but he knocked all the poles. He wouldn't accept it. He thought we were all pagans. But we were baptised. We were Catholics."

Fallon's conversion was, for the Tiwi, the catalyst for a change throughout the diocese and Church. After his apology to the Tiwi, in an act of penance, he wrote to the bishop:

"[Fallon] write a letter to bishop: 'We should leave this cultural thing. That's their culture. They believe in their culture.' Bishop O'Loughlin, yeah, that's him.

"And bishop said, 'All right'.

"He came across and he apologised to all the Tiwi. The bishop apologised. He apologised to Tiwi. He said, 'I didn't know that you had a cultural, a cultural ceremony'."

The archives suggest that this conversation with the bishop took place over many years. In 1967, the Bishop of Darwin, J.P. O'Loughlin, still held that it was doubtful if an Aboriginal person, "thoroughly indoctrinated in his stone age philosophy" by participating in ceremonies could ever "make a success of life in the 20th Century." A Tiwi man corrected him, explaining that they had reached an agreement with Fallon that "it was possible to follow both the European and Tiwi customs."

After much urging from missionary priests, O'Loughlin established a Mission Board in 1968, consisting of priests, nuns, Aboriginal representatives and himself (previously the bishop alone controlled the missions). It went on to promote greater engagement with Tiwi culture on the part of missionaries including through the Nelen Yubu Missiological Unit, established in 1977.

According to Tiwi storytellers, Fallon influenced the other priests and nuns, instructing them on the importance of respecting Tiwi traditions. For the Tiwi, though Fallon went out to shake and destroy the poles, his experience, in fact "shook" the missionaries. It made them re-think their entire mission strategy.

Laura Rademaker is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow in the Australian Catholic University's Institute for Religion and Critical Inquiry, and author of Found in Translation: Many Meanings on a North Australian Mission