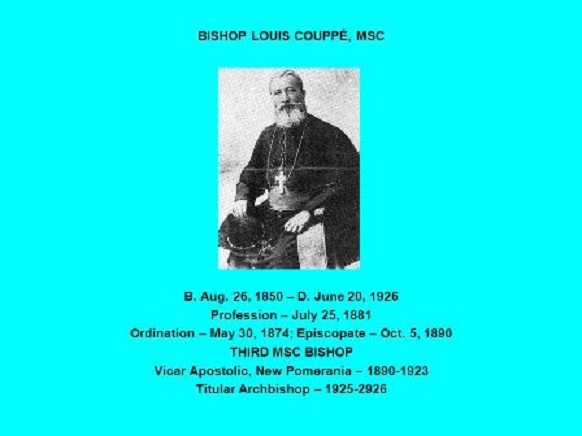

Daughters of Mary Immaculate, PNG, founded by Archbishop Louis Couppe MSC, a World War II 80th anniversary.

When the Japanese invaded Rabaul on New Britain in January 1942, a group of 45 F.M.I. Sisters refused to give up their faith. Instead, they risked their lives to help save hundreds of Australian and European missionaries and civilian detainees who were held captive by the Japanese for three and a half years, first at Vunapope and then in the dense jungle of Ramale.

In 2018, Lisa Hilli, an Australian artist of Gunatuna (Tolai) heritage, discovered their little-known story while researching Australia and Papua New Guinea’s shared war history as part of a creative commission for the Australian War Memorial, supported by the Anzac Centenary Arts and Culture Fund.

It was while she was researching in Rabaul that she first learned of the Daughters of Mary Immaculate, or F.M.I. Sisters, of the Vunapope Catholic Mission. These remarkable Tolai, Bainings and New Guinea Islands women had helped to save the lives of hundreds of men, women and children in New Britain during the Second World War.

Article Claire Hunter, War Memorial

“It was so hard to find any information about them. This is the problem when it comes to archival records about black or Indigenous people; their records aren’t always there, so I had to dig really deep into the archives to find anything about them.

“It’s an incredible story and it’s really important for me to be able to share Papua New Guinean women’s stories, particularly related to war, because women’s stories aren’t always told, particularly in war or the military, and then you add another level of being black or Papua New Guinean, and it’s like, good luck. So to find this, and to be able to highlight it, and reveal it, was just really special.

“It’s a legacy for my own people, so it’s really significant for me to be able to do that.”

For her artwork, Lisa adorned the Sisters with flowers in reference to the different nationalities of the men, women and children who were held captive at Ramale. There’s the iris to represent the French, the poppy to represent the Belgians, the cornflower to represent the Germans, and a Korean hibiscus to honour the South Korean comfort women that were brought over by the Japanese. The wattle in the middle is a reference to Australia and to the Australian soldiers who liberated the camp at Ramale, while the 45 hand-embroidered cinctures represent each of the individual F.M.I. Sisters.

“Only 12 or 13 of these women were photographed, but there were 45 of them, so I wanted to make sure that they were all recognised and honoured,” she said.

“I was really interested in the Sisters’ habit as an item of clothing that signified the practice of their faith. The black cincture they tied around their waist was a very distinct item of the habit that was worn only at the time. They don’t wear it today, and so I kept coming back to it as a really significant piece of clothing from that war history period.”

The four-metre long cinctures were made using a simple black cotton fabric to reflect the Sisters’ modesty, and each is slightly different. The names of 12 Sisters, found on a Memorial in Papua New Guinea, have been lovingly stitched into them, leaving room for more names as they come to light.

“Every time I sat down to stitch into those cinctures, I had to think about the women, and the work and the labour that they did,” Lisa said. “It wasn’t light work what they did, so there was a real heaviness in honouring their names and ensuring that I put weight into stitching every single stitch.”

With Bishop Leo Schamrach MSC of Rabaul

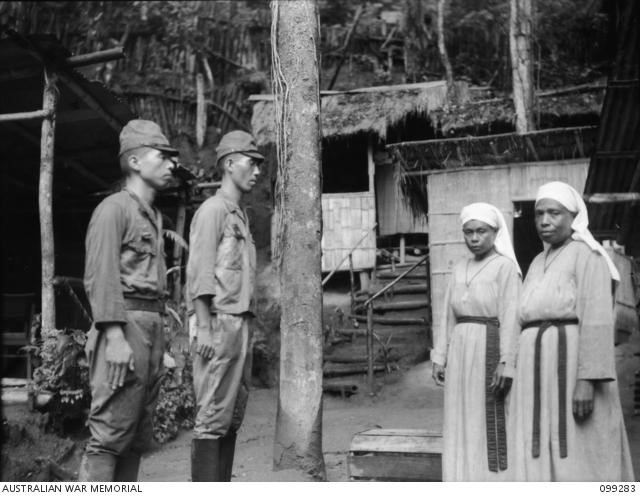

New Britain, 5 December 1945. Two F.M.I. Sisters identifying two Japanese soldiers who had tortured them. A small group of the Sisters were tortured by the Japanese and gave evidence during war crimes trials in 1945/6.

She worked with Australian textile artist and friend, Eddy Carroll, to stitch the names into the cinctures, and has since found 30 more names to add to them.

“It was a real labour of love, and it was a really great way to bring back that Australian/Papua New Guinean connection,” she said. “I hope that the artwork is an entry point for people wanting to know and understand more.

“It was a real gift to have to be able to go into such in-depth research and then make something that I was really proud of…

“They really were amazing women.”

Today