Ben Alforque MSC remembers his arrest, interrogations, torture and faith-testing during the Marcos Martial Law period in the Philippines, in 1973

A story of our confrere and the courage of his convictions. Long but worth reading and considering.

As I begin this narrative, I must confess the fear and trepidation creeping through me again. I had to convince myself of my will to be free, that nothing evil would happen to me. I am angry, I want to cry, I am afraid, I am sad. I feel pity for what had happened and what is happening now. Nothing has changed fundamentally, but I must write so the young people may know.

In June 1973, after graduating from college, I was granted by my seminary superior a year of regency at Virgen de Regla Parish in Lapu-Lapu City, Cebu province. The parish was being served by the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart (MSC). Besides my parish work duties, I continued to do research for a possible master’s thesis on the philosophy of justice in the Filipino context. I had papers on the political, economic, sociocultural and philosophical-theological dimensions of the justice issues, especially among the poor people on Mactan Island—the fishermen, tricycle drivers and tuba gatherers.

Arrest and incarceration

On Oct. 5, 1973, at about 4 p.m., a team of soldiers, riding in military jeeps and trucks surrounded and raided the rectory of Virgen de Regla Parish. Military men and intelligence agents barged into my room, without my knowledge, while I was watching TV with the MSC community. They took my political and economic research papers and my rare coin collection. This last was never seen again. A military officer then invited me to go with the team to the camp. I asked if I needed to bring some clothes. He said there was no need as I would be returning home after answering a few questions.

Together with the parish priest of Virgen de Regla Parish, I was placed in a van, with the military men squashing me between them and preventing me from looking out the window. I was brought to an office, which I later discovered to be the Military Intelligence Group office inside Camp Lapu-Lapu in Lahug, Cebu City.

The officer in charge introduced himself as Lieutenant Managbanag. Right away I was put under investigation by a certain Sergeant Garingalao. For three days and three nights, I was not allowed to sleep. I was not allowed to talk with the other newly arrested detainees. I was falsely accused of being a commander of the communist New People’s Army (NPA) in Leyte province, a period which I spent in its entirety at the seminary.

I was told that I had already been judged guilty, and that my task was to prove myself innocent. I was told further that in the hands of my interrogators, I did not possess anything, not even myself.

I was held incommunicado for two weeks, and placed in the dungeon, a room with double rows of iron bars without any electric light, save for the light coming from outside.

I was threatened with death, and on the penultimate day of my two-week incarceration inside this dungeon, I was asked for my last will. I asked that my parents or family be allowed to see me. My father was allowed to see me for 30 seconds, with the two of us standing on either side of the iron grills.

Psychological, moral torture

It was at this point that I was subjected to psychological and moral torture, and various indignities. First, the tactical investigator, Sergeant Garingalao, talked to me of sex and sexual descriptions, to break me.

That tack not having proved successful, I was made to witness how the uniformed military men tortured the other detainees. I was made to hear the terrible pained cries of detainees from the torture chambers.

Witness to sexual harassment

I was forced to witness the torture and sexual harassment of seven farmers from Samar province that the military had arrested and accused of being NPA members.

The farmers were blindfolded. They were made to face one another and the wall and to throw punches with all their might. They were hitting at each other and the wall, according to the whim of the military torturer. Bruised and in great pain, the farmers were then told to masturbate and drink their own semen.

I could not bear to watch. I covered my face and cried from inside my soul.

During this time of psychological torture, we were fed slop that was splashed on to the cement floor. We had to stoop to eat with our bare hands.

Still, they failed to break me.

Formal investigation

After the second week, I was transferred to Camp Sotero Cabahug in Cebu City, this time under the Philippine Constabulary Command. I was told that was where my formal investigation would be held.

My first investigator was a Sergeant Alega. After three days, he could not get anything substantial from me. So, another special investigator was called to interrogate me. He was a certain Sergeant Rebueno, who I was told was called from Cotabato province just to interrogate me. I was told he was a former high officer in Ateneo de Manila University’s Air Force ROTC. He knew people I knew from the Ateneo student council. It was Rebueno who inflicted me with bodily harm, punching me in the body and belly, but without leaving any marks but reddish skin.

Alega told Rebueno to stop. Sometimes he would stop. Other times he continued the beating, not heeding Alega. I then understood they were playing good cop/bad cop. Alega took the soft, fatherly approach, which I learned later made the other detainees trust him. Rebueno took on the tough-guy approach. He was just mean and cruel.

After seven days of intensive formal investigation, by both Alega and Rebueno, I was finally committed to the Rehabilitation Center for Political Detainees at Camp Lapu-Lapu following a temporary stay with the criminal elements at Lahug Detention Center. Before being brought to a regular detention center, I was taken to see the camp’s military doctor. He glanced at me before signing the certificate that I was well, that I was not tortured or physically harmed. What terrible disrespect for the Hippocratic oath by a medical doctor!

I was in prison for eight months and 13 fruitful days. I was released on May 18, 1974, thanks to my family, relatives and friends who doggedly followed up my case.

Faith regained

No case was filed against me. There was no hearing, no lawyer. But my release papers said the case against me was subversion. I was said to have violated Republic Act No. 1700, or the Anti-Subversion Act.

In the first two months of my detention, I stopped believing in God. There must be no God, and if there was, then he must be a cruel one, I thought to myself. All I wanted was to be a good boy, and now I was imprisoned and psychologically and physically tortured.

There was a Bible and rosary given to me by two Benedictine sisters who were not allowed to see me. I never touched them until one night two months into my detention, when I could not sleep. At about 2 a.m., I got up, and for want of something better to do, picked up the Bible. I opened it, and my gaze fell on John 15:13. It said, “Greater love has no one than this, that someone lay down his life for his friends.” And should they bring you to court and torture you, remember that they did it to me first and worse!

I felt so ashamed of myself. I felt so small because my suffering was nothing compared to that of Jesus. And so I said to myself: “Oh, s**t, God. OK, you win. I will believe in you again. And should I get out of this prison alive, whether I become a priest or not, I will continue to serve you among the poor.” With that decision, I felt free. I realized I couldn’t be imprisoned anymore. No four walls, no power, could ever imprison the human soul. I had declared my freedom. From then on I could do whatever the love of God and service to neighbor impelled me to do.

Judgment is God’s

During the Holy Week of 1974, I asked my military custodians to allow me to attend the Easter Vigil Mass at the chapel of the military facility. The camp commander gave me permission, on the guarantee of the military chaplain, on condition that I should not say a word. I served at the Mass. When communion came, I had to help distribute the Body of Jesus. Coming toward me to receive Holy Communion were some of our torturers and their military bosses up to the rank of general who had ordered our torture and terrible detention.

I had to make a split-second decision: Should I or should I not give them Holy Communion? In that moment I realized that this was not about me, and not about my judgment on them. It was about Jesus and his invitation to them. Between those moments of torture and their coming for communion, many things could have happened that I did not know. Judgment lay in the hands of Jesus, in their relationship with him. I surrendered in my heart. I gave them Holy Communion, the Body of Christ.

Those moments convinced me that there are really few truly evil people in the world. The words of Jesus on the cross, ringing with compassion and profound understanding of the complexities of the human heart, of the human condition, rang clearly: “Father, forgive them for they do not know what they are doing.

Editor’s Note: The author was a member of Makabayang Samahan, the college students’ arm of Kapulungan ng mga Sandigan ng Pilipinas, as a college student at Ateneo de Manila University. He was active in organizing the students in Metro Manila for what was then called the Democratic Left movement. After his release from military detention in 1974, he was placed under house arrest, city arrest and provincial arrest in Cebu. He was not allowed to go back to the seminary for a year.

While studying theology at Loyola School of Theology, Quezon City, from 1976 to 1980, he had to regularly report to the Philippine Constabulary in Cabanatuan City, Nueva Ecija province, and later, at Camp Crame. He was ordained in 1979. The next year, he left to study biblical exegesis at Pontifical Biblical Institute in Rome, thanks to the intervention of Jaime Cardinal Sin who secured a permit for him to travel from the office of Gen. Fabian Ver.

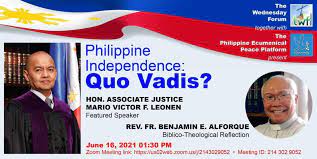

He returned in 1985 with a licentiate degree in sacred scripture, taught at Maryhill School of Theology, was dean of studies at MSC Sacred Heart Scholasticate and consultant to the Office of the President and moderator of the Communication Foundation for Asia.

He became a founding member of Selda, and later of Karapatan, while being actively involved in education for justice and peace. He served as parish priest of San Luis de Gonzaga Parish, was district superior of MSC Agusan District, vicar forane for the Diocese of San Bernardino in California and is now back with Communication Foundation for Asia.