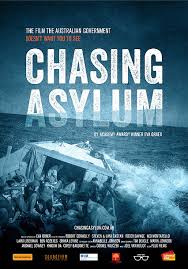

CHASING ASYLUM, A TIMELY DOCUMENTARY - AND FOR ELECTION WEEKS

CHASING ASYLUM

Australia, 2016, 97 minutes, Colour.

Directed by Eva Orner.

Although this sounds something like an understatement, Chasing Asylum is a documentary that should be seen by every Australian, especially by every politician. It is a film of special pleading rather than bias (as it has been accused of), cinema documentation of the plight of asylum seekers and refugees in the Detention Centres on Nauru and Manus Island.

The writer-director, Eva Orner, has credible credentials. She spent a decade overseas producing documentaries, most notably Alex Gibney’s Taxi to the Darkside which won her a producer’s Oscar.

Concerned about the asylum issues, especially after the Tampa incident in 2001 and the coalition government’s response, issues about which all Australians are concerned (although in different ways in their support or non-support of the asylum seekers), Eve Orner began this project, filming in 2014, able to film footage secretly on both Nauru and Manus, striking images, shocking images which are reminders of the extraordinary inhumanity experienced by those detained. The point is made that those in Australian prisons who have committed crimes know the length of their sentence and possibilities for parole – but that the asylum seekers and refugees are detained indefinitely. And what is that condition responsible for in terms of mental apprehension a deterioration, let alone all the other repressions and harsh conditions that they experience?

The film gives some outline of the history of dealing with asylum seekers and refugees, Nauru after 2001, the people smuggling, the boats arriving or being lost at sea with large loss of life, the concerns about border protection, the Sovereign Borders policy, the stopping boats policy as well as the turning back of the boats, the 2014 decision that no boat person would ever settle in Australia. The film also indicates the physical and mental deterioration of so many men and women, also children, the sexual abuse, the deaths of the Iranians in riots or by Coalition or Labor.

But, some whistleblowers have been interviewed, some identified and seen by face, others just by suggestion and voice. Of these, some were employed by the Salvation Army. The manager of one of the centres is also interviewed, expressing his dismay. And the appointee, who had worked in prisons, expresses his revulsion about conditions, about death threats to him were he to speak publicly, and his resigning in disgust, unable to help. One of the young women, who is motivated by selflessness to go to Nauru but not realising what it was like, the repercussions for the people as well as for herself, is very direct and has a lot to say which needs listening to.

The film does not try to find any solutions for coping with people smugglers, turning back the boats or not, or other political stances. What it does do is to show the inhumanity to men, to women, to children, in putting them indefinitely into sub-standard, often unsanitary, conditions, tents and huts, communal facilities, that could alarm an audience watching this film and trying to imagine how they would deal with being put in similar situations.

A point is made that the two Iranians who died seem to be economic migrants, especially when the families of both men are interviewed in Iran – but, of course, there are economic migrants everywhere (including many who came in past decades to Australia). Their claims have to be considered along with others but there is no need for them to be dehumanised along the way. We are reminded that there are Conventions about migrants and refugees that Australia has signed up to.

While the following points are not made in the film, watching the film makes an audience realise that the asylum seekers have come from different cultures, communities, colder geographical climates, dietary differences and makes them ask whether any acknowledgement is made by the authorities at the Centres, for language, for religious traditions, for the roles of men and women in these societies, in the need for children to grow as children with play and education.

This is a documentary for this particular time – and its release during the very long election campaign of 2016. It is a cinema document that will be important in decades to come as later generations look back and ask questions about policies and humanity in the treatment of asylum seekers and refugees.

There is a dedication of the film to Malcolm Fraser who, at the time was not considered to be left-wing or a bleeding heart, was able to deal with large migrations of Vietnamese in the aftermath of the Vietnam war, setting up offshore processing which moved comparatively rapidly and then bringing those approved to Australia by air and settling them. And the question is asked why this cannot be done now.

Peter Malone MSC