HANNAH ARENDT

The MSC Justice Desk recently printed quotes from philosopher, Hannah Arendt.

The quotes are featured. Around Australia, a film, called Hannah Arendt, who coined the phrase, 'The Banality of Evil' after witnessing the trial of Adolf Eichmann. The SIGNIS review is included below.

'Education is the point at which we decide whether we love the world enough to assume responsibility for it, and by the same token save it from that ruin which except for renewal, except for the coming of the new and the young, would be inevitable. And education, too, is where we decide whether we love our children enough not to expel them from our world and leave them to their own devices, nor to strike from their hands their chance of undertaking something new, something unforeseen by us, but to prepare them in advance for the task of renewing a common world.'

Hannah Arendt

'No punishment has ever possessed enough power of deterrence to prevent the commission of crimes.'

Hannah Arendt

'When all are guilty, no one is; confessions of collective guilt are the best possible safeguard against the discovery of culprits, and the very magnitude of the crime the best excuse for doing nothing.'

Hannah Arendt

'Revolutionaries do not make revolutions! The revolutionaries are those who know when power is lying in the street and when they can pick it up. Armed uprising by itself has never yet led to revolution.'

Hannah Arendt

HANNAH ARENDT

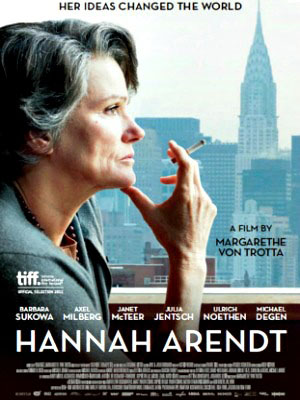

Germany/Israel/Luxembourg, 2013, 113 minutes, Colour.

Barbara Sukowa, Janet Mc Teer,

Directed by Margarethe von Trotte.

Hannah Arendt was a significant thinker in her time. She had written on the Origins of Totalitarianism and was appreciated as a philosopher. Jewish, she had escaped with her mother from Germany in the late 1930s to the United States and became an American citizen. She lectured in New York and was esteemed as a woman of depth and intelligence.

This is a film which is of interest to those who know about Hannah Arendt, her life and career. It will also be of interest to those who know little about her but want to find out her contribution to 20th century thinking. If an audience is not interested in Hannah Arendt and her work, they will find this sometimes detailed look at her and her philosophy hard going, or too-hard going.

The director, Margarethe von Trotte, has had a long career in film but has concentrated so many times on significant women and women’s issues. Her leading lady for Hannah Arendt, Barbara Sukowa, has appeared in several of the director’s films playing, amongst others, Rosa Luxembourg and Hildegard of Bingen. Here she creates a very strong impression as Hannah Arendt.

The principal focus of the film is Hanna and on Adolf Eichmann, his being taken by Israeli agents in Argentina, his extradition to Jerusalem and his trial, where he was held in a glass cage, and ultimately found guilty of the charges and hanged.

Hannah Arendt asked the editor of the New Yorker to report on the trial. Her husband, Heinrich, was against her going. But, wanting to ground her philosophical reflections in facts and experience, she was determined to go. The film has some brief scenes of the trial, Hannah sitting in the benches, working in the press room watching the television screen, and some actual television footage of Eichmann himself, the prosecutor and the judge. There are several re-enactments, as well as footage, of some of the witnesses and their emotional response to the treatment of the Jews and the Holocaust. Looking at Eichmann, we see a small man, very ordinary-looking, a bureaucrat rather than any charismatic leader. This was to be the core of Hannah Arendt’s comments on the trial.

After the publication of the articles in the New Yorker, there was a groundswell against Hannah. Jewish authorities and many of the Jews, whether they had read her articles or not, felt that she had betrayed her people, especially with her comments about the complicity, witting or unwitting, of some Jewish leaders with the Nazi authorities and so being responsible for more deaths of Jews. For many this was incomprehensible, leading to hostile phone calls, letters and death threats.

But Hannah Arendt was a strong character, accused of arrogance (which is displayed in the film) and a lack of feeling. However, influenced by the philosopher, Martin Heidegger, with whom she had a relationship when she was a student, rejecting him when he affirm Nazism and later visiting him to ask him to make a public apology, she was a philosopher who was also passionate, invoking ‘passionate thinking’.

The dramatic finale to the film is a lecture she gave at the New York New School, in the presence of the University officials who wanted her resignation, and to a full room of students. It is here that she speaks the phrase which most people know, even if they do not know who originated it, ‘The Banality of Evil’. Eichmann was an ordinary man, a bureaucrat, not a man with a vision or leadership qualities, but someone who obeyed orders because he believed in the authority and that the authority should be obeyed, passing on his orders to others who fulfil them while he was detached, not even knowing necessarily what the consequences were. This is a particularly important message at any time, but particularly now, where communications and social media give us immediate information about all kinds of laws, persecutions, atrocities.

Perhaps this film is more of a visual lecture about Hannah Arendt than an inventive cinema experience. But, to the extent that it portrays Hannah, her ideas, and the controversies about the Eichmann trial and her reporting, it is worth seeing.