Peter MALONE

Quest for Love

QUEST FOR LOVE

UK, 1971, 91 minutes, Colour.

Joan Collins, Tom Bell, Denholm Elliott, Laurence Naismith, Lyn Ashley.

Directed by Ralph Thomas.

The synopsis of the film indicates science-fiction; the title and the treatment indicate 'Love Story'. On the whole, the latter wins in an English but sentimental way. But the science-fiction ideas (based on a John Wyndham story) are worthwhile; what if time were not one unbreakable continuum, but could be split and people live in two simultaneous but different worlds? This basic premise is interestingly used and provides also a kind of Jekyll and Hyde theme where the one character has two quite different personalities and lives. An enjoyable film and, via the love story, very easily acceptable science-fiction.

1. What were the expectations of this title? Their fulfilment? How enjoyable was the film, how much warmth?

2. Which predominated: science-fiction or the love story? Which aspect of the film was better? Why?

3. What presuppositions do audiences have for science-fiction? The role of science, progress, imagination and fantasy, warnings for dangers. fears? Grappling with contemporary problems via science-fiction fable? How did this film do this? Well ?

4. How well did the film blend in the love story and the science-fiction? For whom was this film principally made? Why?

5. How credible was the plot? Was it presented credibly? The authentic London backgrounds, the relationships of facts and dates? The types of personalities involved? Everything recognizable to the audience yet strange?

6. The fascination of time and its mystery? Was the plot. as regards time, possible? The theories of the professor? What was really real? Did the film explain its theories plausibly?

7. How interesting was the theme of identity? The basic Jekyll and Hyde story? The insight into potential of each individual by portraying his two possible characters? Dissatisfaction with one world and imagining another? How interestingly and excitingly was this portrayed?

8. How well did the film cater to audience imagination about comparisons of the present world with another one? A world without war? A world with a different progress? Which of the two worlds was better? Both were 1970's worlds. List the pros and cons of each world and make comparisons. The film finished in the real world, so to speak. Was this preferable?

9. How well did the film involve us in the mystery? The explosion and the sudden transition to the other world without explanation? Should Colin have explained?

10. How easy was it to identify with Colin and share his mystery and bewilderment? How did the film contrive this for the audience?

11. Comment on the two Colins and their contrast: the good and the bad, selfish and selfless, using people, the search for identity etc? what insight into being human did this comparison give? The details of the two lives for comparisons?

12. The character of Ottilie - in herself, her capacity to be hurt, the heroine, having a second chance with life, the melodrama and pathos of her death, the effect on audiences and its handling - at the piano? The comparison with Tracey in another world? The chase, the optimism? Was this too facile a solution? How attractive was Ottilie-Tracey? How did this aid the film?

13. Contrast with Toms in each world. What comparisons were made?

14. The contrast with the two professors? The role of the professor in explaining the mystery? And a touch of humour?

15. How was this easy science-fiction,, romantic communication of science-fiction messages?

Quest for Fire

QUEST FOR FIRE

France, 1981, 95 minutes, Colour.

Everett Mc Gill, Ron Perlman, Rae Dawn Chong.

Directed by Jean- Jacques Annaud.

Quest for Fire was a film both acclaimed and criticised on its first release. It is an ambitious Canadian- French co-production filmed all around the world from Scotland to Africa. The scenery and the use of locations is excellent.

However, the screenplay by Gerard Brach (writer for Roman Polanski for such films as Tess) is more controversial. It is an adaptation of a French children's fantasy of 1911 by one of the Boex brothers under the pseudonym of J. H. Rosny. The film also has special language created by Anthony Burgess and special body language and gestures by Desmond Morris (The Naked Ape).

With this background, the film is intended as a reconsideration of primitive cultures. The argument is that there has been too glib a presupposition about the primitive nature of early man. This film wants to show basic human behaviour in 80,000BC or so. What emerges, however, is a big-budget variation of such B-budget films as When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth. Perhaps the material is difficult to present and can appear to be ludicrous to sophisticated audiences. Some have dismissed the film as being merely a variation on the One Million B.C. kind of film. Others have seen it as an excellent presentation of ancient history. In advertising, it was linked with the impact of 2001 : A Space Odyssey in its time. Direction is by Jean- Jacques Annaud, director of the award-winning Black and White in Colour, the picture of colonialism in Southern Africa at the opening of World War One.

1. The acclaim awarded the film? Its cult value? The quality of production? Quality of insight?

2. Audience presuppositions about primitive life? The land, animals, life styles and behaviour, values? A different interpretation of the past? The interpretation of the human heritage and its origins? The past examined in the light of present behaviour? Hopes for the future?

3. The film's stances on evolution? Physical evolution? Psychological evolution? The emergence of moral values?

4. The impact of the 70mm photography? The wide range of locations for pre-history? The suggestions of a prehistoric world - landscapes, animals, weather? A recognisable world for 20th. century audiences? The blend of beauty, savagery, mountains and plains, caves and rivers, swamps? The changing seasons? Animals: predators, the mammoths, killers, cubs?

5. The contribution of the make-up: how realistic? Showing the transitions in the evolutionary pattern? The different styles of the Ulams, the Wagabous, the Kzamms? The nature of the differences? The importance of the language and the sounds? Anthony Burgess called it 'agglutinative' - babble rather than the formation of primitive words? The contribution of the body language?

6. The importance of fire and the title of the film? The traditional meaning of fire? Real? Symbolic? The power of fire? The holding of fire and power? The use of fire? The loss of fire and the search for it? The tribes holding the fire, knowing how to make it? The conflicts for fire, the learning and sharing of how to make fire?

7. Audience interest in the plot? The primitive lines of the plot? Naoh as hero? In his own place? His companions, mission? The swamps and the dangers? The tracking? The cannibals, the tigers? The encounter with Ika? The love for her? Her tending him? The nature of the journey, the encounter with the mammoths, the pursuit? The encounter with the Ivaka and learning? The bear? The escapes, the fights? Naoh's final achievement? The symbolism of journey and adventure, quest and endurance?

8. The presentation of the various tribes: their appearance, manner, make-up, language, gestures? Clashes, communication, jealousy?

9. How well delineated were the characters? How was this possible within the scope of the film? Naoh as hero? His companions and their loyalty? Ika as heroine? The presentation of emotions - love, loyalty?

10. The film's making parallels with contemporary behaviour and primitive behaviour? Good and evil, violence, love, sexuality?

11. A plausible picture of the origins of human behaviour? Human achievement? The value of the primitive era?

Querelle

QUERELLE

West Germany, 1982, 104 minutes, Colour.

Brad Davis, Franco Nero, Jeanne Moreau.

Directed by Rainer Werner Fassbinder.

Querelle is the final film of Rainer Werner Fassbinder. it is a highly stylised production, uses the Panavision camera but is a chamber work. The sets are highly stylised: the hotel at Brest, the ship, the alleys and the streets of the city? There are backgrounds which highlight the colours of orange, gold and brown.

The film is based on Jean Genet's 'Querelle de Brest.' It is an adaptation and interpretation of the novel. The screenplay was written by Fassbinder with Burkhard Driest (who portrays Mario).

The film has an international cast including Franco Nero as the Captain, Jeanne Moreau as the proprietor of the hotel and Brad Davis (Midnight Express) as Querelle.

Fassbinder seems more interesting in the visual presentation of his play rather than in the development of characters. There are Brechtian captions throughout the film, a voice-over interpreting people's behaviour as well as moving the action on. This has the effect of involving the audience as well as distancing them.

The film deals, as does Genet's work, with homosexuality, concepts of masculinity and femininity and the enclosed world of men. Fassbinder, himself a homosexual, explored homosexual themes in The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant and Fox and His Friends as well as in In The Year of Thirteen Moons. In the cast are people involved with gay films such as Frank Ripploh and Michael Mc Lernon. Director Robert van Ackeren as does Volker Spengler who was the star of several of Fassbinder's films.

Genet's world is idiosyncratic, difficult for an audience to identify with and understand. This stylised presentation is Fassbinder's testament to his filmmaking and his life.

1. The work of Fassbinder? Interest in themes, style? The work of Jean Genet? A homosexual world view?

2. The stylised set: Brest, the Feria Bar, the ship? The use of colours? Symbols, especially phallic symbols? Panavision and the scope of the images? Angles, editing and pace? Viewpoints? The use of mirrors and reflections? The transcending of period: the ship, the tape recorder, the drugs?

3. The use of the male choir as background? The song adapted from 'The Ballad of Reading Jail' by Oscar Wilde, 'Each man kills the thing he loves,? The Catholic background, the procession and the Passion of Christ, the choreographed fight in the street with the procession?

4. The function of the voice-over? Its impact? The narrator, the Captain and his tape recorder? The pros and cons of the device? Emotional distancing, information given? The voice-over doing the emotional work for the audience? Time and action jumps? The effect, the distancing?

5. The use of parallels: the brothers, their similarity and differences? Two halves of the one being? The use of mirrors, reflections? The same actor playing Robert and Gil?

6. The perspective of Jean Genet: the quotations and the captions? His world view, flesh and spirit, sexuality? The screenplay and its explicitness? Homosexuality in this world? Prison, the Navy, the enclosed world? The role of women and their presence and absence? Jill and Roger and the talk about Paulette, identify in Roger with Paulette, the photographs? Lysiane and her owning the bar, the relationships? Men and relationships with men? Masculinity, hedonism, sexual experiences, love and affection? The world of homosexual cruising, brutality? Masculine identity? Dominance and submission? Sexual experience and the criminal experience? Crime as a work of art, needing to be recognised, the lone lines of the artist criminal? Punishment and salvation? The final information concerning Genet?

7. The Feria Bar and its world, the tableau? Nono and his relationship with Lysiane, being black, big, his experience, relationship with the men in the bar, Mario? The rolling of the dice and the rules? His relationship with Lysiane? With Querelle? His disdain of Robert and his passion for Querelle? The sailors and the workers, Roger? The phallic symbols in the glass and outside? The music? Drinking, dancing, sexual relationships? A microcosm? The world outside the bar, streets and alleys, the wharf, world of drugs, police and motor bikes, murders, the religious procession?

8. The Lieutenant and his tape, a voyeur, isolated, observing the men, Querelle, the graffiti and his writing his own, his passion and his being caught, being robbed by Jill? His being wounded? His knowing the truth, letting Querelle off, accusing Robert? Querelle's judgment of him. his submission to him? In himself, the voice of passion? Passion exposed?,

9. Lysiane as the main woman, the observer, her song, Jeanne Moreau's presence, relationship with Nono, with Robert, the hostessing, sexual relationship, with Querelle and being humiliated by him? Her final declaration that Robert had no brother?

10. Querelle as central? Brad Davis and his physical and psychological presence? Pictured as a homoerotic icon? Bare, sweaty, covered with coal? For the characters? For the audience? The impact on the Captain? On Mario and the others? On Nono? His work, submission and respect for the Captain? Meeting Robert, the rivalry? clashes, the choreography of the fight? His drug deals? Killing the sailor? Committing a crime and its effect? The voice-over explaining his psychological understanding? Nono and his deliberately losing, the sexual encounter, his passivity, his talking about discussions with Mario and the seduction and the experience?

11. The encounter with Roger? Gill and his identifying with him, emotionally? His disguising Gil as Robert for the robbery? Giving him the gun? Giving of the information to the police? His revenge on Lysiane and his attitude towards women? The police, his being saved by the Lieutenant, submitting to him? A weak man? His experience, philosophy, world view? the world? The contrast with Robert and his view of the sailors, hard work and sweaty, the bar, in the bunks, the sexual discussions and rivalries, drugs?

12. The helmeted workers, their lives, relationships, Gil and his encounters with Roger, the discussions about Paulette, Paulette identified with Roger, his fascination with Querelle, Querelle persuading him that he had done both murders, the robbery and the disguise, the shooting of the Lieutenant, the arrest and his acceptance of responsibility?

13. A portrait of individuals, of a society? A coherent world view - acceptable to an audience or not?

Que le Bete Meurt/This Man Must Die

QUE LA BETE MEURE (KILLER! or THIS MAN MUST DIE.)

France/Italy, 1969, 110 minutes, Colour.

Michael Duchaussoy, Caroline Cellier, Jean Yanne, Anouk Aimee.

Directed by Claude Chabrol.

Que Le Bete Meure is based on a novel by Nicholas Blake (the pen-name of poet laureate Cecil Day Lewis, father of Daniel Day Lewis). It was directed by Claude Chabrol, a master of suspense thrillers whose films during the 1960s were outstanding in presentation of French families and moral crises, generally including violence and/or marital infidelity. This continued during the 1970s. Examples are The Unfaithful Wife, The Butcher. Chabrol, however, witness to continue to make a wide range of films into the 21st century.

While the film shows an ordinary situation, tragic as it is, a father grieving over the death of his son in a hit-run accident, it is a powerful film on obsession as well as vengeance and the moral challenge to the father of how he deals with his grief as well as his antagonism towards the hit-run driver. It is an expert film in the Chabrol vein of exploring the dark side of human nature and of ordinary people.

This Man Must Die shows how emotional crises and violent chance events alter personalities. Since the late 50s, director Claude Chabrol, has been interested in these strange changes. Lately he has used the thriller form for his explorations. Here he examines the change in a man whose son is killed by a hit-run driver and who pursues this killer to execute him. At times this is presented in a cerebral manner and we feel we are watching an illustrated casebook of revenge and conflicts of motives. At other times, some scenes are so alive - a pre-dinner drinks and dinner scene is outstanding - that we feel for the people involved. More psychological than thriller.

1. The significance and tone of this title? An alternative title was "Killer". How much more appropriate? The original French was "That the Beast Must Die". Was this more appropriate? The emphasis on the beast? How bestial was Paul? What is the nature of his beastliness? (The hero then identifying with some of this beastliness in his revenge?)

2. The contribution of the colour, locations, the musical accompaniment and its classical tone? Controlling mood?

3. The opening idyllic nature of the child? Audience lulled into sympathy and interest? The importance of this initial mood? How was this mood suddenly changed by the hit-run accident? Audience indignation and horror? The fact that it was a child? The nature of hit and run? (The beastliness).

4. How credible and convincing was the father's grief? How moving? why was his son important to him?

5. Did this explain the nature of his obsession? why was he so obsessed? Why did it drive him? Was it something inside himself? Or was it solely the response to his son's death? Comment on the film as a working out in detail of an obsession? Revenge as an obsession? How credible? How much did the audience share this?

6. Comment on Charles’s shrewdness and his seeking out of clues and following them up. The detailed visualizing of this? His plans, the nature of fate and providence chance and luck? (The themes of providence and chance in the revenge obsession?)

7. How well did Charles insinuate himself with Helene? With the family? What right did he have to do this? The effect on him. on them? Audience response to this insinuation. or did they share the obsession?

8. The influence of love? The relationship between Charles and Helene? Was this credible? His working on Helene for her breakdown for information? The violence on her privacy?

9. The presentation of Paul as a character? Was there any audience sympathy? Was he a beast to all? The way he ruled his family, wife, relations, the effect on his son? The amount of hatred towards his beastliness? The obsession strengthening when seeing the quarry?

10. The nature of the obsession working into hunter and hunted? The detail of its working out? The psychological significance?

11. The impact of such sequences as the drinks, the evening meal? How well filmed? Atmosphere? A revelation of inter-relationships?

12. The importance of Philippe in the film? His relationship with his father? Hatred to death? The linking of Philippe with Charles in obsession?

13. The drama of the cliff, the fall, the boat? The device of Charles’s diary and the plan to murder? Why did he save Paul on the cliff? How credible? Audience approval or disapproval of this?

14. The final confrontation and Charles’s shrewdness? What had happened to his revenge?

15. Philippe and his identification of guilt? His confession? Charles assuming guilt? The identification of the two? Who was really guilty in his heart?

16. How credible were the psychological overtones of this thriller? Did it give it credibility and depth?

17. The use of thriller techniques for suspense? How satisfying a thriller? It is considered a classic. Does it deserve this reputation?

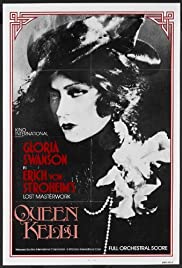

Queen Kelly

QUEEN KELLY

US, 1928, 99 minutes, Black and white.

Gloria Swanson, Walter Byron.

Directed by Eric Von Stroheim.

Queen Kelly is a reconstructed and restored version of an ambitious silent film directed by Erich von Stroheim. It starred Gloria Swanson and was produced by her (with the financial backing of Joseph P. Kennedy). It was considered extravagant in its day and the star closed the production before it could be completed. Various versions of the material were edited, sometimes changing the plot-line. Gloria Swanson kept it and exhibited it as part of her exhibitions and tours during the decades. During the '70s and '80s, work was done in finding as much material available as possible, discovering a copy of the original musical score as well as von Stroheim's notes about sound effects. The finished product (from a copy which was very well preserved) has most of the original material and some bridging material as well as indications of the developments of the plot.

The film's strength lies in its visuals, the genius work of von Stroheim. The black and white photography, compositions, contrasts are all excellent.

Von Stroheim was responsible for the screenplay - and on this level the film is rather ludicrous. The film shows a mythical kingdom with a mad Queen Regina, jealously in love with Prince Wolfram. The scenes of this middle European kingdom look like satires on The Prisoner of Zenda and other films. Gloria Swanson is Patricia (Kitty) Kelly, a girl at a Catholic orphanage abducted by the Prince. She is in love with the Prince and the Queen is jealous. There are all kinds of melodramatics including Kitty attempting suicide by diving into the river. She is rescued and brought back to the convent. There are many scenes of prim convent life. Kitty learns her aunt is dying, goes to German East Africa, finds that her aunt is the owner of a brothel, she marries a plantation owner and becomes Queen Kelly at the brothel (the old woman is present at the wedding and receives the Last Rites!)

The film was supposed to have a second part when Kitty would have become Queen Kelly. The film summarises the melodramas (and absurdities) of the 120s silent films. It is of interest as a museum piece.

Quartet/1948

QUARTET

UK, 1948, 120 Minutes, Black and White.

The Facts of Life: Basil Radford, Naughton Wayne, Jack Wattling, Mai Zetterling, James Robertson Justice.

Directed by Ralph Smart.

The Alien Corn: Dirk Bogarde, Honor Blackman, Irene Brown, James Hayter, Francoise Rosay.

Directed by Harold French.

The Kite: George Cole, Hermione Baddeley, Mervyn John, Susan Shaw, Bernard Lee.

Directed by Arthur Crabtree.

The Colonel's Lady: Cecil Parker, Nora Swinburne, Linden Travers, Ernst Thesiger, Wilfrid Hyde White, Felix Aylmer.

Directed by Ken Annakin.

Quartet is one of the many films of Somerset Maugham's stories. Popular over many decades, films of his works were made by American companies, eg. The Letter with Bette Davis and Herbert Marshall and The Razor's Edge with Tyrone Power. British contributions to Maugham films were three selections of short stories: Quartet, Trio, Encore.

Quartet is very interesting and entertaining, taking us back into an old British world of the first part of the 20th century. Maugham observes accurately but seems to be making points about the individual who has a capacity for insight, art or skill which runs contrary to ordinary British expectations. This point is made quite forcibly to several of the stories. Prominent stars in the British cinema of the time played important roles of the stories eg. Dirk Bogarde, Cecil Parker. R.C. Sheriff, the playwright of Journey's End and frequent screen-writer adapted the screenplay which included an introduction by Maugham himself. The piano concertos are played by Australian pianist Eileen Joyce. A good introduction to the world of W. Somerset Maugham.

1. An interesting and entertaining British film? The style audiences are now used to from television series? Its place in the transition from the British film industry to television industry? Its impact as cinema now?

2. The work of W. Somerset Maugham and its popularity over the decades? Maugham's estimate of himself and his comment on what the critics said over the decades? His popularity amongst readers, amongst theatre-goers, amongst film-goers? The effect of having him introduce the film? The respect for Maugham as a novelist, short-story writer, observer of human nature?

3. The technical aspects of the film: having four different directors, the use of prominent British stars of the time, black and white photography, the score, the very British settings?

4. What common threads were evident during the film? British themes, British society and class, the remnants of the old world, old British manners and values? Individuals within these worlds and their self-assertion in arts or skills and the common expectations and reactions against them? The overall impact of these four glimpses of aspects of British society?

a) THE FACTS OF LIFE.

1. The impact of this short story as an introduction to the whole film, its slight tone, its ironies, the humorous punch-line contrasting tennis and cricket - and the implications for British attitudes?

2. The portrait of the father talking to his friends at the club, the club manners and games, talk and drinking? The father's values and old British traditions? His attitude towards his son and his advice to him, his being unwilling for him to go to Monte Carlo? His talking with his wife and adviser, his changing his attitude on the advice of his wife? The importance of the tennis sequence focussed entirely on three people talking and watching the game at the saw time?

3. The character of Nicky - his skill at tennis, naive young man, his attitude towards his father's advice, the temptations of Monte Carlo, his being persuaded to gamble, giving the money to the woman, his surprise at its being returned and his falling a victim to her persuasions? Talking together and not realizing the irony of what she was saying, the meal together, the return to her hotel, being robbed? The portrait of the naive young man?

4. The irony of the advice and his explanation of it? The fact that he should regain more of the money and the ironic comment?

5. The portrait of the confidence woman at the casinos of Monte Carlo, her techniques and persuasiveness, the irony of her losing her money?

6. The irony of the advice and the father's ultimate attitude?

b) THE ALIEN CORN.

1. The conventional material about the earnest young man and his unconventional career? The serious ending? The irony of the jury's statement as an expression of British attitudes - and the audience thinking that it knows better?

2. Dirk Bogarde's style as George? The earnest young man with his hopes? The very British type? The expectations of his parents, the sympathy from Paula? His determination, his gratitude to Paula for her intervention, his going to Paris and working, his confidence, his moods, especially with Paula as regards love, piano playing? His hopes for achievement and the experience of failure? His asking the pianist to play? His decision to clean the gun - did he kill himself or was it an accident? was he capable of killing himself after this experience of failure?

3. The portrait of his parents - country types, their expectations and traditions? His uncle and the offer for the job? Their mocking George's attitudes, permitting him to go? Their response to the recital, especially his fidgety father? The fact that they would lose their son?

4. Paula as heroine - her love for George, helping with the arrangements, her being fair to him, the visit to Paris and his playing for her? Her memories during the recital? Her grief at the ending?

5. The pianist and her presence, listening, the brutality of her speaking the truth and its effect? Her skill in her own piano playing? Could she be blamed for George's death?

6. The court, the jury and the irony of its verdict? The point being made about art and individuals?

c) THE KITE.

1. The title, the suggestion of puzzle? Moving towards a solution and the speculative solution offered? True, sentiment?

2. The setting of the tone with the prison and the prison visitor, the introduction to Preston and his interview with Sunbury and his reaction to him, the discussion with the Prison Governor?

3. The story by the Governor and the flashbacks to Herbert Sunbury as a boy, his relationship with his parents, the bond through kite flying, the sense of achievement, control, soaring? The kite as a symbol of Herbert? Of his parents?

4. How accurate a picture of the family group? The sympathetic father, the possessive mother? Herbert as relating to them both? The joy of the kite flying, the inventiveness and creativeness? The patterns that were emerging in his life and were to be disastrous for him?

5. Betty as a contrast to the Sunbury family? Herbert's mother's idea of Berry and seeing her intrude? Betty's arrival and her attitude towards Mrs. Sunbury, calling Herbert, Bert, her independence? The visit and her clumsiness? His parents not being at the wedding? Her hold over Herbert especially as regards the pictures, her ridiculing of kite flying? Her being hurt, packing his things? Collecting the money? How credible was her smashing the kite? Preston's intervention for their reuniting and her flying the kite? A credible portrait of a believable young woman?

6. Herbert at home, his change? From being prim to falling in love, the conflict of kite and wife? His marriage and his longing to fly the kite, watching his parents, going back to them and being under his mother's thumb? His willingness to go to jail and his prim comments about Betty? Was it credible that they should be reunited - did he really love her?

7. The portrait of Mrs. Sunbury in herself, her manner, her attitude towards Be 9, possessiveness over Herbert, having him back and treating him as a child, her surly attitudes towards Betty? why couldn't she let him go?

8. The credibility of the ending and the use of sentiment and feeling?

d) THE COLONEL'S LADY.

1. The British tone of this episode, British values, the theme of poetry and British reaction to it, expectations? The film as a love story?

2. Cecil Parker's style as George? The very British type, his taking his wife for granted, his lies to her and his liaison with Daphne? The irony of his attitude towards the book of poetry, his pretence of reading it? The fact that he did not? His growing awareness with the reaction of friends, the reviewer at the club, the bookseller, the party and the comments of the women, the American publisher, Daphne and her telling the story? The impact on him?

3. His saying that he was a man of the land, his taking his wife for granted and then the move to jealousy and the impact to get the truth?

4. The portrait of Evie - ordinary at home, her appearance and dress, glasses, living for her husband and making decisions in line with his wishes? Her being left at home? The book that she had written and her pleasure in it? The gradual revelation of the kind of book that it was and audiences seeing her through George's eyes and the eyes of the readership and critics?

5. The audience's reaction to the gradual revelation of the contents, its being a best seller, the importance of Daphne's story? The importance of the confrontation and the tenderness with which Evie told the truth? The revelation of love and a dead relationship?

6. The style of the 40s and the emphasis on the book of poetry in the light of "Lady Chatterley's Lover" and Lawrence's reputation and subsequent court cases? What point was Maugham trying to make about such literature? How wise was the observation of human nature, manners and morals? The acuteness of the observation of the English way of life in the middle of the 20th century?

Quality Street

QUALITY STREET

US, 1937, 82 minutes, Black and White.

Katharine Hepburn, Franchot Tone, Fay Bainter. Eric Blore. Cora Witherspoon, Estelle Winwood.

Directed by George Stevens.

Quality Street is a play by J.M. Barrie and directed by George Stevens who was to make Gunga Din, Penny Serenade at this time. The film is an English period melodrama and a vehicle for Katharine Hepburn. She is quite good and had appeared some years earlier in the Barrie adaptation of The Little Minister. The film has an old-fashioned atmosphere and at times is quite quaint but nevertheless enjoyable.

1. The impact of this film? As a film of the 30s, now? A Katharine Hepburn vehicle? The tone of the title. its ironies?

2. The atmosphere of J.M. Barrie's plays? Their old world atmosphere? Re-creation of period in style and manner? Characters within this specialised environment? Human issues within this environment? The atmosphere of the 19th century? How appropriate for 20th century audiences?

3. The old-world style and yet the content and the treatment as romantic soap opera? Did the characterisations and the situations transcend romantic sentimental soap-opera?

4. How well did the film re-create the English world at the turn of the 17th century? The atmosphere of English village life? The preoccupations with the trivia of village life? Attitudes on Quality Street? The contrast with the atmosphere of the Napoleonic wars.. patriotism, men enlisting, the effect of the war (even though remote) on the people in the village?

5. The film's focus on the Throssell sisters: entering into their world, into their house, their manner, profession? The details of their behaviour? The contrast between Fanny and Phoebe? Fanny as the older sister. the spinster? Phoebe and her not wanting to finish like Fanny? The bonds between the two?

6. The world of the doctor? The build-up to his being a romantic hero? Phoebe's expectation of his proposal and her disappointment when he enlisted? Her romantic attitudes towards him? Idealising him? His enthusiasm for the war. his joy in telling Phoebe. his marching along with the enlised men?

7. How well did the film make the transition of ten years pass? Audience response in imagination to the wars, the passing of time.. Phoebe getting older and unmarried? The experience of the doctor at war?

8. The doctor and the welcome after the war? The return to normality? His love for Phoebe.. the experience of Phoebe's pretending to be her niece? His bewildered reaction to the advances of Phoebe?

9. Fanny and her getting older. a normal spinster? Her concern for Phoebe? Her reaction to Phoebe's deception?

10. What had happened to Phoebe over the ten years? How spinsterish had she become? Her way of life.. manner, talk? Her regrets for the past? What motivated her pretence? The contrast in the two personalities that she portrayed? (Katharine Hepburn's style in presenting the two characters?) To what purpose the deception?

11. The farcical aspects of the deception situation: at home, at the dance? Her pretence? Her knowing of the truth?

12. How satisfying was the resolution of the problem? A romantic ending -appropriate for this kind of film?

13. What points were being made about human nature, society.. environment, history and its shaping of people's lives, happiness and disappointment?

Q, The Winged Serpent

Q - THE WINGED SERPENT

US, 1982, 92 minutes, Colour.

Michael Moriarty, David Carradine, Candy Clark, Richard Roundtree.

Directed by Larry Cohen.

Q - The Winged Serpent is a very enjoyable animal menace fantasy. It was written and directed by Larry Cohen - whose films include similar horror fantasies like It's Alive, It Lives Again, Demon (God Told Me To) as well as The Private Files of J. Edgar Hoover.

The film uses the atmosphere of New York City excellently, has special effects for the winged serpent and its gory killing of people. It also uses echoes of such films as The Exorcist but combines them with the atmosphere of blood sacrifice Mexican religions. The film has an excellent cast, relying on Michael Moriarty as the ordinary petty criminal who sees the chance to become a hero in the newspapers because of his discovery of the serpent. David Carradine is good as the policeman.

Tongue-in-cheek and offbeat - but probably more persuasive and frightening because of it.

1. An entertaining horror thriller? Its use of the monster and menace conventions? Satire? The popularity of the film among buffs?

2. B-budget style, the sets and styles of the old serials and B films? Jokey tone?

3. Special effects and serpent (real and rubber), the murders, the subjective shots for the monster, gore? Editing and pace for flight, chases, shootouts?

4. The musical score, the songs: Let's Fall Apart Together Tonight, Evil Dream?

5. The quality of the cast and their contribution to the credibility and enjoyment?

6. The flip start setting the tone, the decapitation, the sunbathers, the worker and the sandwiches - the range of victims? Flip Callous? The variety of deaths - the flayed victims, the pool man, the police? The cinematic variations on the gore trend?

7. The picture of the police: David Carradine as the effective policeman, slightly seedy, dedicated to his work, his clashes with his assistants especially Sergeant Powell? The contrast with Powell - and his being killed? Shepard and his liking for music, the jazz, the bar, the discovery of Jimmy Quinn? His research, discoveries about the Mexican religions, reports, the city authorities and their reaction? Interrogations? Fight? The clashes with the monster? With the human villains? The clashes with Quinn, using him? The hero of the film? The contrast with Powell and his being the antagonist? The sketch of the city officials, their attitude towards the city, criticisms, meetings and authorisations, cover-ups, taxes etc.? Corruption, ego? The film's comment on the New York papers and the jibe at Rupert Murdoch? The critique of the city, its lifestyles, people, judgments, fear, social anger?

8. Jimmy Quinn as the petty thief, participation in the jewel robbery, driver, running away, pursued by fellow criminals, escape into the Chrysler Building (and the irony of the Chrysler Building and its pinnacle looking like the monster)? His discovery, going to the police, the media, his bargaining with officials about money? The sleazy criminal, ambitious, shrewd? His relationship with Joan, support, his further adventures, being caught up with the strange religions, with the monster, his being threatened, the promise to reveal the hiding place, Shepard saving his life?

9. Joan and her sharing Jimmy's experiences, trying to understand, support?

10. The monster, visual, special effects? Flying over the city? The monster's eye view of the victims, the swooping on the victims, the killing? The terrorising of the city - and the city looking upwards (as in the old B-movies of the '30s and '40s)? The aura of the Mexican religions, human sacrifice, the legends? The victims? The masks? The symbolism of the monster - serpents, devils, angels, wings, the whole aura of religion not understood?

11. Shepard and his pursuit, study, the rituals, the bodies, the chase and the confrontations? The heroics? The fanatics involved in the religion, their backgrounds, what motivated them? The bringing together of the themes of gore, religious possession, petty crook, police thriller? The irony of the resolution - and, of course, another egg being broken open and a monster emerging?

14. The popularity of this kind of nightmare adventure? Comic book style? A successful use of thriller conventions?

For Queen and Country

FOR QUEEN AND COUNTRY

UK, 1988, 105 minutes, Colour.

Denzel Washington, Amanda Redman, Bruce Payne.

Directed by Martin Stellman.

For Queen and Country is the directing debut of Martin Stellman, co-writer of this film and writer of the very interesting nuclear, journalist, cover-up conspiracy thriller, Defence of the Realm, directed by David Drury (1985).

This is a portrait of the ugly side of Thatcher England in the '80s. Denzel Washington portrays a West Indian British citizen who has served in Ireland, the Falklands, Africa and Central America who returns back to England with no prospects. Even under the 1981 British Nationality Act, those born in St Lucia? are no longer considered British citizens. He wanders squalid city landscapes, encounters racist police, drug-dealing, terrorist bomb-making, petty thievery. He becomes involved as a bodyguard for a drug deal. In the meantime, he meets a sympathetic woman whose daughter has been involved in robberies. There is a possibility of friendship and love - and making some future. However, with the combination of his friend going berserk, the lack of prospects for employment, the pressure by the police, he gives information to the police which builds up to a violent showdown and his death. The film is grimly pessimistic.

Denzel Washington brings dignity and strength to his performance. The rest of the cast is not well known except for George Baker as a more sympathetic detective.

Small budget, intensely felt, perhaps a jaundiced look at Thatcher England - but a strong critique.

1. Impact of the film? Drama? Social comment? Pessimism?

2. Small-budget production, a slice of British life in the '80s? The background of the Irish troubles, Kenya, the Falklands? East London as a new war zone? Location photography, the slums of the east? Style of film: darkness, shadows, ugliness, landscapes, human isolation? Editing and pace? Effects and stunts? The atmospheric score?

3. The title and its irony, especially for Reuben? For all soldiers? The quotation from Cromwell about his soldiers? The 1980s and England?

4. Denzel Washington as Reuben: how persuasive? Credible West Indian in London? The background in Ireland, the heroics, the rescue? The Falklands and action? Drinking in Ireland, the ambush, the shooting, the reliance on Fish?

5. 1988 and his discharge, his background, hooligan, transformed by military service? His hopes? British citizenship, birth in St Lucia. The changing of the laws in 1981? His passport, the bureaucracy, the frustrating visits, using his army connections and not being understood? The final resolution of the bureaucracy and his passport?

6. His flat, dinginess, settling in, making it his own? Making contacts for jobs? No possibilities? Visiting Fish and establishing friendship? The Estate and its ugliness, the building, slums? The pub? Robberies and stealing? Aimlessness? The racism? The police and their brutality, harassment?

7. Reuben and his past, racial issues, the army, the possibilities? Depression? Army buddies? Meeting Stacy after the episode with Haley? Enjoying her company, out? The fair? Witnessing the concrete dropping and the death of the policeman? Silence? The frustration, the police wanting information? Stolen goods? His decision to be the bodyguard for the drug transaction, his behaviour, caution? The arrest and his breaking of the contract? The pressure by Kilcoyne? Linford, the deals, the making of the bombs in the tunnel? The confrontation with Fish, trying to get him to go to St Lucia? The attack of Linford, the gun, Fish talking him into giving up the gun, his death, shot by the bigoted policeman? Bob, the army marksman, shooting Reuben? Hopelessness?

8. Fish, his injuries, the background in Ireland, his pregnant wife, his leg, his angers and his drinking, remembering, the bond with Reuben, the collectors and the thugs, the night with the girl? His wife and the birth? Her leaving? His angers, the final confrontation, his death? Trapped in London?

9. Colin, friendship with Reuben, their talks, job prospects, contacts, the possibility of working as a bodyguard, the drugs and the protection? The people involved in the drug deal, the restaurant and the toilets? The Indian's arrest?

10. The atmosphere of crime on the Estate, the pub, the kids robbing the gangs, the stolen goods, the making of the bombs?

11. The picture of the police, Challoner and his racism, harassing Reuben? The interrogations? The final confrontation and Reuben killing him?

12. Kilcoyne, decent, the question of harassment, law and order, trying to get information, surveillance, the questions of Reuben and Stacy? Keeping up the pressure, Reuben finally giving him the information?

13. Stacy and Haley on the Estate, the encounters, the friendship, the outings, Reuben telling the truth, their being harassed, refusing to give evidence? Stacy and the story of her husband and the guns?

14. Images of Thatcher England, poverty, inequality, racism, loss of opportunity? Elitism? Military, drugs and bombs? Reuben's death and the hopelessness?

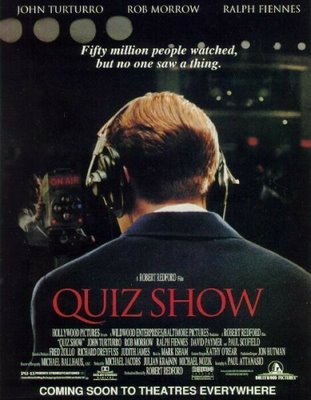

Quiz Show

QUIZ SHOW

US, 1994, 130 minutes, Colour.

John Turturro, Rob Morrow, Ralph Fiennes, Paul Scofield, David Paymer, Hank Azaria, Christopher Mac Donald, Elizabeth Wilson, Alan Rich, Mira Sorvino, Paul Guilfoyle, Griffin Dunne, Illeana Douglas, Calista Flockhart, Barry Levinson, Martin Scorsese.

Directed by Robert Redford.

Quiz Show is the re-creation of the late 1950s in New York City and Washington DC with the famous quiz show, 21. Highly popular in this decade of television, it was finally revealed by a senate inquiry that the show was rigged. John Turturro appears as Herb Stemple, a simple Jewish contestant from Brooklyn who ultimately reveals that the questions were fed to him. He is contrasted with Ralph Fiennes as Charles van Doran, the son of a socially prominent and intellectual family whose father was a Pulitzer Prize-winning poet. Paul Scofield is excellent as the genial patrician elder van Doran. Elizabeth Wilson is his wife.

The film also focuses on the company executives, the head of NBC (played by Alan Rich) and the head of Geritol, the product that sponsored 21. Martin Scorsese appears as the icy smiling head of Geritol. David Paymer and Hank Azaria are very good as the network officials who take the fall.

There is a strong humanity about the film, especially in showing three different families, the Stemples, the van Dorans and the family of Richard Goodwin (Rob Morrow) on whose book and investigations the film is based.

1. The acclaim of the film? Its portrait of American culture, American media in the '50s? Critique?

2. The strength of the cast and their skills? Robert Redford's direction? Paul Atanasio's writing?

3. The settings of New York City and Connecticut, Brooklyn in contrast? Washington DC? The atmosphere, decor and costumes of the late '50s? The television studios, the shows and their style? The musical score? The contemporary songs in background?

4. The prologue and Dick Goodwin and his being tempted to buy a new car? The shiny car, power, money, winning, ambition? The screenplay based on his book and perspective?

5. The portrait of Dick: young, ambitious, relationship with his wife, at home, ordinary? His capacity for relating to people? His background, first in his class at Harvard, his work in the various investigations? The challenge of investigating and 'getting' TV? Interest in the quizzes, watching them, checking the information, the bosses, the newspaper items? His concern about the questions, his list for visiting contestants? The meeting with Charles van Doran, a sense of equality despite wealth and class and race, friendship? Eating with him, playing cards (and the use of lying instead of bluffing)? Going to his home and observing the birthday dinner, the gifts, the poetry? His visit with Herb Stemple, talking with him, going back to him, preparing him for giving evidence? The contestant who revealed that the questions were in the post? The various hearings, the visit to Charles and trying to persuade him to stay in the background, to tell the truth? The subpoena? His confronting Enright and their discussions, giving him the proof, controlling him, the NBC head and his iciness - and the remark about who was sweating? The head of Geritol and the surface smiling and the sparring about the issues? His watching the final episode for Charles van Doran and seeing him smile? Charles and his asking would he take the money, his refusal? His desperation at Herb's evidence and humiliating himself? The final hearings, Charles van Doran's confession? Watching him on the steps? The contrast of class, wealth, Jewish and non-Jewish Americans in the late '50s?

6. The staging of the quiz, the 21 points, the nature of the questions, the booths, microphones and headphones? Jack Barry and his vanity, in the mirror, his genial hosting, self-importance? The irony of his giving himself away on the filmed evidence when the question was answered correctly? Herb and his questions, answer - and his later explanation of all the techniques for mopping his brow, bursting out with enthusiasm - and illustrating how Charles van Doran did the same? The issues of money? Dan Enright and Al Freeman, the producers, their moral attitudes, unscrupulous about fixing the quiz? Dan and his shrewdness, Al and his vulgarity? The head of NBC and his ruthlessness? The head of Geritol and his watching the program, controlling, wanting Herb off? Issues of ratings, sponsorship and money? The audience and their 1950s dress, manners? The enthusiasm in the studio? The range of home audiences all turning on? The decisions about Herbie having to go?

7. Herb Stemple and his wife, the son, their simple home, Brooklyn? His intelligence, his becoming a TV celebrity, welcome and congratulated in the neighbourhood? His arguing with Enright, the issue of Marty and his having to make a decision about the fall? The scene of his decision and his getting the answer wrong? His reaction to van Doran, jealousy? His being hurt, the meal with Enright, pleading, wanting to be a TV personality, the deal? His being ousted, anger, revenge? Psychological treatment? His interviews with Dick, revealing the truth about the questions, the rehearsals? His dressing for the hearings, his relationship with his wife, her disappointment, feeling one of the public who was tricked, yet supporting him? His performance, his humiliating himself - and her feeling humiliated in the hearings? His return for van Doran's confession? The issue of Jewish and non-Jewish contestants? His being used?

8. The contrast with Charles van Doran, his wealth and position, his father and his reputation? The relationship between Charles and his father, his father's genial dominance, Charles wanting to prove himself? Watching TV, enthusiasm for the quizzes? At home, relationship with his family, class distinctions? Going to the audition, Dan picking him, Al supporting him, the rehearsal of the questions about the Civil War, explanations of the set-ups, asking him questions that he knew? Later posting them? Charles taking each step and going further in his fall? His beating Herb? The interview with Dave Garroway and his becoming a TV personality? The collage of his success, the accumulation of weeks and his winnings, the students coming to his classes, public adulation, his waiting and wanting to be seen later and not wanting to be seen? The question to continue or not? The meeting with Dick, his concealing the truth, yet finding a friendship with Dick? How much wanting to really confess? The dinner at his parents' home, the birthday, knowing King Baudouin, bandying quotes from Shakespeare with his father? The gift of the television? The poker playing with Dick, discussions about truth and lying? Bluffing? Wanting out, the reactions of Enright and the others? The sequence of eating the chocolate cake and discussing with his father and his inability to tell him? Wanting to go back to past innocence? His final mistake and smiling as he went out? Garroway and the dealings behind the scenes as the executives wanted him to stay, offering him the contract, the plausible argument about education in America? His denying the truth to Dick? The head of NBC coming to the studio to the make-up room and putting on the pressure? His telling the truth to his father? His parents coming to the hearing, his prepared speech, his sincerity, the Senate praise - yet the senator who said that he was merely telling the truth? The press conference, the end, going into the taxi, looking at Dick? His subsequent career?

9. Mark van Doran and his reputation, New York aristocracy, suave and genteel, his books, lectures, family discussions, his birthday party, his not being able to watch 21 because of the suspense, listening to Charles, supporting him in Washington? His mother, her style, reputation, literary ability? The family and the birthday party?

10. Dan Enright and Al Freeman: decisions, rigging the show, choosing the contestants, dealing with them? Answerable to the executives? The phone calls, watching the monitors? Handling Herb? The issue of not knowing Marty? The choice of van Doran, their talk, defying Dick Goodwin? The evidence of the questions in the post? Al going to Mexico? Their coming back to testify? Their being the fall guys? Truth, entertainment, show business? Subsequent careers?

11. The executives, their power, personalities? The head of Geritol and his smooth talk, grinning - yet sinister, lying? Their testimony at the hearings - and their friendship with those on the bench?

12. The TV world, Jack Barry and the film evidence, Dave Garroway and the interviews? Publicity, advertising?

13. The committee, the personnel, knowledge of those being interrogated, playing golf? The young men like Dick Goodwin coming up?

14. The collage at the end? Television winning? Issues of truth and lies, bluff, magic and sleight of hand, entertainment - and audiences not expecting the exact truth? Audiences and motives? Quizzes, competition, the money?