Peter MALONE

Saturday, 18 September 2021 18:56

Star Wars Episode 3: The Revenge of the Sith

STAR WARS EPISODE 3: REVENGE OF THE SITH

US, 2005, 140 minutes, Colour.

Ewan Mc Gregor, Natalie Portman, Hayden Christensen, Ian Mc Diarmid, Samuel L. Jackson, Jimmy Smits, Frank Oz, Anthony Daniels, Christopher Lee, Temuera Morrison, Kenny Baker.

Directed by George Lucas.

Yes, it is a pleasure to say that this episode worked perfectly.

After living in the memory of the Star War films of the 1970s and 1980s, most found The Phantom Menace to be a huge disappointment. George Lucas had come back with a lumbering, too often corny Episode I in 1999. It was a relief in 2002 when Episode 2, Attack of the Clones, was better, but it seemed an interim piece. There were hints of how Annakin would go over to the Dark Side, but it was not clear just how he would become Darth Vader.

Now, all the questions are answered. At the end of Revenge of the Sith, there is a really strongly felt urge to see the Luke Skywalker episodes again. And, it is worth congratulating George Lucas in bringing his epic to a satisfying conclusion.

The first young audience for Star Wars is now in its 40s. They will really enjoy this episode answering questions they have had for years. The new fans will like it too, though it is worth remembering that Star Wars was never intended for small children.

Revenge of the Sith moves right into action. There is quite a lot of ‘whizz whizz bang bang’ in the opening battles. Special effects are much bigger and better than they were. We then move into the personal drama: Padme is pregnant and Annakin in happy anticipation of being a father. The other aspect of the drama is that Obi-Wan? Kenobi is finding Annakin restlessly ambitious, still repeating the Jedi code, but increasingly resentful that, though he is a member of the Council, he is not permitted to be a Master.

The Jedi rescue Chancellor Palpatine and he soon reveals his true self as he fulfils his ambition to be emperor of the Galaxy. In a more convincing psychological screenplay than for the previous films, Lucas is able to show how the Chancellor introduces Annakin to the Dark Side, the temptation of power. Shrewdly, he promises that Padme will not die in childbirth. He promises that when Annakin destroys the Jedi and the separatists in the outer boundaries of the galaxy, he will have achieved peace. This means that Annakin does the wrong thing for the right reasons.

The consequences are devastating for the Jedi, especially Windu and Yoda. The consequences are also devastating for Annakin himself. His cruelty foreshadows his evil as Darth Vader. As anticipated, there is a climactic duel between Annakin and Obi Wan Kenobi, leaving Annakin burnt and disfigured. We watch his being reconstructed and the now well-known mask fitted over his face (and the audience literally cheered).

For decades, many religious education teachers have been able to alert students to the deeper meanings in these replays of myths of chivalry. In this episode, they can explore the nature of evil, of how democracy can turn into despotism. (There is more than a touch of Manicheism – the theory of two equal sources of good and of evil - in the explanation of The Force, having its good side and its dark side, but the film does dramatise selfless and selfish decisions and responsibilities.)

With the birth of Luke and Leia, with Obi Wan leaving to train Luke, we are back at the beginning. We now know how situations and characters came into being, not only the evil Emperor but R2 D2, 3PO and Chewbacca.

Ewan Mc Gregor continues as Obi Wan Kenobi. Hayden Christensen does very well as Annakin and makes his choices for evil and his transformation believable. This time Ian Mc Diarmid as the Chancellor become Emperor has a much bigger and more important role. The effects are very effective and John Williams score is as rousing as ever.

1. Audience expectations, the work of George Lucas, his vision? The fulfilment of his work?

2. The film and its place in the series, completing the six episodes, ending the first half, preparing for the second half?

3. Popular entertainment, popular over decades: the Star Wars, the galactic battles, life in the galaxy, the Empire, the range of characters, the range of creatures, robots, the conflicts both social and personal?

4. The focus on the Empire, power, democracy, the loss of democracy for despotism and tyranny? Good and evil? The Dark Side? The Force? The quest for order and peace in the galaxy?

5. The title, the role of the Sith, their being in league with the Dark Side of the Force? The contrast with the Jedi and the other inhabitants of the galaxy?

6. The structure of the film, battles, politics, personal drama, conflict, transformations into good and evil?

7. The battles, the information at the beginning of the film, the galaxy and the Empire, the control of the Sith, the rebels, the lords? The rescue of the chancellor? The droigs, the fight with Lord Dooku? His skills, techniques, the laser swords, the battle with Obi Wan Kenobi? The flight, taking the chancellor, the difficulties in the lift well? The chancellor and the escape? Setting the scene, raising the issues?

8. The character of Anakin, his age, the training by Obi Wan Kenobi, his role as a Jedi, his speaking the code? In fights, supporting Obi Wan? Yet rebelliousness, restlessness? Obi Wan as the master, seeing Anakin as a brother, their collaboration together? Preparation for the drama of their falling out?

9. Padme, her love for Anakin, their secret marriage, her pregnancy, his wanting to be a master, his attitude towards the senate and council, her wariness? Anakin’s nightmare about her dying in childbirth? Preparing for his choices for the Dark Side?

10. The chancellor, his contriving the battles, his own kidnapping, the rescue? His lust for power, communion with the Dark Side? Human nature? The Sith and the desire for power? The troops, the clones? His discussions with Anakin, his antagonism towards the council, his suspicions, insinuating ideas into Anakin’s head about the council, about the Jedi, spying for him and his realisation that Anakin had been asked to spy for them? His using Padme as an influence for Anakin and his choices?

11. The Jedi, their code, the range of knights, the twelve in the council, Mace Windu and his status? His hard attitudes towards Anakin? Refusal of his requests? Asking him to spy? Yoda and his wisdom in the council? The other members, the meetings? The decisions about the outer boundaries, not sending Anakin, sending Obi Wan Kenobi?

12. Obi Wan and his mission, arriving at the planet, the lord and his warnings about the trap? The battle – and Obi Wan establishing peace?

13. Anakin, the influence of the chancellor, his own restlessness? His decision? The reasons for his choice? The mission in the Empire? His ruthlessness in destroying the children, the massacres of the Jedi knights? The effect on him? Going to Padme, his explanations, love for her, his lies, denouncing Obi Wan?

14. Padme and her fears, travelling to the planet, discussions with Obi Wan and not believing him, the discovery of the truth, her horror at the change in Anakin, her grief?

15. Anakin and his talk of hatred for Obi Wan, the fight, Obi Wan winning, Anakin and his burning?

16. The reconstruction of Anakin in his armour, the mask, his breathing – becoming Darth Vader?

17. Padme, giving birth to the twins, naming them? Yoda and his decisions, Senator Organa and his continued loyalty, taking Leia to his wife? Obi Wan taking Luke to his home planet? The glimpse of the future?

18. The popularity of the mythology, its place in worldwide imagination since the 1970s? The Force, the confrontation between good and evil, power and despotism, heroics, romance, fate? And the possibility for peace and order as the ultimate goal?

Published in Movie Reviews

Published in

Movie Reviews

Tagged under

Saturday, 18 September 2021 18:56

Last Days

LAST DAYS

US, 2005, 95 minutes, Colour.

Michael Pitt, Lucas Haas, Asia Argento, Scott Green, Nicole Vicius, Ricky Jay, Hamni Korine.

Directed by Gus Van Sant.

As a cinematic aesthetic exercise, Last Days will fascinate cinema buffs who enjoy beautiful portrayals of the enigmatic. And it looks good as well. Others will find it tedious and, perhaps, trite in its treatment of the burnt-out star. It is in the vein of his Gerry – but makes Elephant seem hyperactive.

Van Sant has written as well as directed and declares that he has drawn from the last days of Kurt Cobain in his depiction of Blake (Michael Pitt in a well-wrought performance). Which means that we watch, often stare at length, at glimpses of a rock star in mortal decline: loss of self-confidence and the will to perform, drugs, fickle friends and hangers-on or, in the words of his final song, ‘it’s a long, lonely journey from death to birth’.

While van Sant wants to offer a tribute-interpretation of artists like Cobain, the world he offers is a mixture of grunge and nihilism that seems hopelessly depressing. Peggy Lee, long before, sang ‘Is that all there is?’

1. An aesthetic cinema work? The content? The interplay of the two?

2. The work of Gus Van Sant, style, perspectives? An interpretation of the last days of Kurt Cobain?

3. The New York State settings, the woods, the mansion, the interiors of the house, the town, the club? The combination of wealth and squalor?

4. The rock music background, the soundtrack, the selection of songs, especially ‘The Long Lonely Journey from Death to Birth’?

5. Kurt Cobain and the burnt-out careers of rock stars: fame, audience, applause, exhaustion, mental and moral breakdown, physical breakdown? The heritage of the music? What remains after the collapse?

6. Celebrities, agents, audiences, record companies and agents, concerts, friends, hangers-on?

7. The visual style, the long takes, the sparse dialogue? The episodic nature of the film, especially the visit of the Yellow Pages man, the Mormons, the visit to the club? Blake talking to himself, singing to himself?

8. The scenes resembling his mental state, repetitions, his knowing what was going on, not knowing, memories, memory loss? Individuals appearing and disappearing?

9. The opening in the woods, the choral background, the walk, the swim, sitting by the fire? The return to the house, breakfast, his getting meals during the days? Ignoring the phone? The people in the house, Scott and Asia? The visit of the Yellow Pages man, the conversation, his being out of it? Wandering, passing out in the house, avoiding Donovan (twice)? Back into the woods, playing, singing, listening to Lucas and his pitch, going into town, the conversation in the club, going to the tool house to die? The image of his death, his coming out of himself, climbing to heaven? The final realism of the police arriving, taking away his dead body?

10. Scott and Asia, sleeping in the house, interactions with Blake? Scott and his conversations? Lucas, in himself, the sexual liaison? In Blake’s mind or imagination? His discussion about his sexual experiences, the song, wanting Blake to help with the lyrics? Nicole and the other visitors? Scott and the visit of the Mormons, their explanation? The scenes of eating, sexuality, the coming and going in the car? Friends or not?

11. The drive with Donovan, the detective, the discussions about Blake, looking around the house, his avoiding them?

12. The Yellow Pages man, his earnest pitch? The Mormons and their pitch? The significance of these episodes for Blake, for the others? Blake’s conversation with the man in the club?

13. The particular world or universe that Blake inhabited? Questions of identity, existence, life and death?

14. The film illustrating the song, ‘The Long Journey from Death to Birth’?

Published in Movie Reviews

Published in

Movie Reviews

Tagged under

Saturday, 18 September 2021 18:56

Matrix Series, The/ SIGNIS STATEMENT

THE MATRIX

and religious symbols

December 1st 2003

With Matrix Revolutions, the American screenwriters and directors, the Wachowski Brothers (Andy and Larry) have completed what has been one of the most popular and talked about film trilogies. While The Lord of the Rings showed us Tolkein's world and took its audiences into the mythical past and used religious symbols and motifs, The Matrix trilogy takes audiences into a future that is no less mythical and which also uses religious symbols and motifs.

With the release of The Matrix in 1999, audiences both young and old responded to its exploration of the relationship between humans and modern technology. Philosophers around the world hurried to write articles for academic journals on how it raised the problems of what is real, what exists only in the mind and the possibilities of co-existing dimensions. Noted Catholic Polish director, Kzrystoff Zannussi, a member of the Vatican's Council for Culture was of the opinion that the film was a contemptorary masterpiece and that people should see it, not only because of its extraordinary special effects but also because of its intellectual stimulus.

Matrix Revolutions, released around the world on the same day and the exact same time, became a talking point for religious educators and theologians. A world where human-created computers and machines now hold the humans to ransom and who burrow through the earth to destroy them and their refuge city, Sion, can only be saved by Neo, an anagram of the One.

The first film in The Matrix trilogy introduced Neo as a Saviour-figure, someone human (or programmed like one) to be the means of saving the human race. In death and resurrection imagery, he was killed and then loved back to life by the warrior, Trinity. In Matrix Reloaded, the saviour role of Neo is developed but left in abeyance until Revolutions. By Matrix Revolutions, Neo is still the Saviour-figure par excellence, referred to by his enemy, Bane, as 'the blind messiah'. In apocalyptic imagery, with overtones of biblical battle imagery, he saves the bereft humans in the city of Sion and confronts the Satan-figure, Mr Smith, and is seen, arms outstretched as on a cross. His blinded eyes see an internal vision, glowing beauty, a kind of 'beatific vision' which culminates in his final apotheosis.

While the Wachowski Brothers drew on all kinds of popular sagas and mythology, their use of names with Christian-overtones for their characters as well as imagery that is familiar from biblical stories, mean that there can be fruitful dialogue between the movie and the scriptures.

The descent of Jesus into 'hell' or 'hades' or 'to the dead' is an article of the Apostles' and Nicene Creeds. Speculation in the early decades of the Church are echoed in references in Matthew's Gospel, the letter to the Ephesians as well as the suggested readings from John and I Peter. The tradition suggests that, while Jesus died for all, his death led him first to be associated with those who had gone before and were waiting to rise to new life with him.

The Jewish scriptures are full of battle imagery where God conquers the enemies of Israel as they do battle with their foes. The tour-de-force battle scene in Matrix Revolution, where the machines finally bore down to the city of Sion to destroy the humans, is replete with spectacular war machines, desperate human weaponry to ward of the enemy and terrible destruction of the humans. It is useful to read chapters 38 and 39 of Ezekiel, the chapter of Armageddon, so beloved by fundamentalist and rapture Christians. Gog of Magog has a plan to destroy Israel but is no match for the power of God. God's warnings are given through the prophet. Perhaps the Wachowskis know Ezekiel. However, the machines are like Gog, overwhelming forces for destruction. The warriors of Sion are like the harassed people of Israel. Like Ezekiel, there is an Oracle who prophesies and guides, especially to lead the hero, Neo. These biblical battles provide a context for Jesus' descent to the Dead.

The overview is given in I Peter 3:18-20: Jesus' mission at his death is to go to those who have remained faithful, even if they have sinned, and rescue them. The letter uses a parallel with God's patience for those who remained faithful at the time of the deluge (and goes further to parallel the deadly deluge with the saving waters of Baptism). Now, the dead can be 'baptised' and saved through Jesus' presence.

Since Neo is the saviour, he is pictured in Matrix Revolutions going down into his own 'hell'. He is betrayed by Bane, blinded by him. But his inner vision leads him to guide Trinity above the machines to a safe vision of clear and beautiful skies before he descends to do battle with Mr Smith. Part of his 'hell' is the sacrificial death of his beloved Trinity. As the power of megalomaniac Smith (Satanic in its delusions of grandeur) seems to conquer him, he goes into a grave before he regains the strength (with the images of Neo, arms outstretched) to finally defeat Smith.

In this connection, the sayings of Jesus in John 5:24-30 are evocative: the special hour coming, the dead hearing the voice of Jesus, those good people in the tombs rising to new life because of Jesus doing the will of the Father who sent him on his mission. As Smith asks in bewilderment during their battle, 'Why'. Neo answers, 'Because I choose to'.

Of course, many viewers will look at The Matrix trilogy as exciting science fiction or futuristic fantasy. Some will respond, according to producer, Joel Silver, just on the visceral level. Others will respond to the mythic layers. A Catholic response will explore those mythic levels and discover the links between the scriptures, Jesus of the Gospels and the religious symbols. For audiences who are not sure of their faith or their biblical knowledge, the films provide aspects of a new apologetics, a contemporary invitation to examine the credibility of the Catholic tradition.

Published in Movie Reviews

Published in

Movie Reviews

Tagged under

Saturday, 18 September 2021 18:56

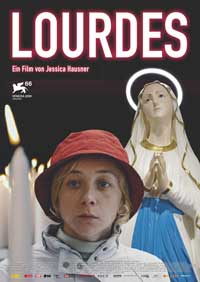

Lourdes/ SIGNIS STATEMENT

LOURDES

14th September 2009

For almost 150 years, Lourdes has been an important centre for pilgrimage and prayer. The story of Bernadette Soubirous, the apparitions of Mary, the digging of the spring, the abundance of water as well as the many cures and healings are well-known because of the experiences of the faithful, the questions of sceptics like Emile Zola as well as Franz Werfel's book, The Song of Bernadette, and the 1943 film version with Jennifer Jones. Bernadette also featured in two French films, Bernadette (1988) and The Passion of Bernadette (1989), directed by Jean Delannoy, with Sydney Penny in the title role.

The new film, Lourdes, is a project written and directed by Austrian Jessica Hausner who has a Catholic background. However, she does not approach the subject from an explicit Catholic point of view. Rather, she wanted to put on the screen the Lourdes pilgrimage experience and to raise the issues of the nature of God, the possibility of miracles and the 'fairness' of God in granting healing to some and not to others.

The film-makers discussed the project with the bishop of Tarbes, where Lourdes is situated, and received collaboration during the making from the shrine authorities. It is certainly a film Catholics can be comfortable with, the presentation of devotion and faith, the range of perspectives of the pilgrims themselves, the experience of healings. The questions the film asks are those that believers and non-believers must ask.

The film shows a group of French pilgrims, with their chaplain and assistants from the Order of Malta, following the rituals of the visit to Lourdes: the grotto, the Eucharistic blessing, confession, processions, bathing in the water... The central character, Christine, has severe MS and is paralysed. She has come with some devotion but, principally, for a trip. The elderly lady she shares a room with is prayerful and solicitous for her. During the pilgrimage, Christine feels a growing strength and seems to be healed. There are various responses from the group, joy and suspicion, and the film is open-ended concerning Christine's future.

CRITICAL RESPONSE AND AWARDS

Lourdes screened in competition at the Venice Film Festival, September 2009. Critical response, even from reviewers avowedly hostile or wary of Catholicism, tended to be very positive, a surprise in itself. Lourdes won awards from SIGNIS, the World Catholic Association for Communication (the jury making the point that the award was not simply because of the Catholic topic but also because of the quality of the film and its probing of faith and miracles). The Catholic Ente dello Spettacolo also gave the film its Navicella award.

However, Lourdes also won the award of the Federation of International Film Critics, FIPRESCI, an indication of the merits of the film since this award is made for excellence in film-making as well as for exploration of themes. Yet, the film won no award from the main jury at the Festival. Writer Stephanie Bunbury, The Age, Melbourne, 14th September, suggests that the French were wary of the possibility of miracles and to make an award to Lourdes would be 'unethical'. (She refers to this type of reasoning as 'bone-headed'!)

More puzzling is the fact that Lourdes was given the Brian award. This is an annual collateral Festival prize named after the character, Brian, from Monty Python's Life of Brian. It is made by the association of rationalists and atheists. Did they interpret the film as, minimally, a sceptical look at the phenomenon of Lourdes or, more strongly, as an attack on the 'irrationality' of faith and miracles?

WHAT THE AUDIENCE SEES

For Catholics, Jessica Hausner has presented the Lourdes experience in generally accurate and extensive detail. Cast and crew sometimes mingled with actual pilgrims. (The prelate for the Eucharistic blessing is Cardinal Roger Mahoney of Los Angeles.) Those who have visited Lourdes will have memories stirred. The sequence where Christine speaks of her angers and frustrations to the priest in confession rings true as does the scene in the smaller room where pilgrims ask for personal blessings.

Non- Catholics have been puzzled by as well as in some admiration for what they see. The gathering of the sick seems to some just like one of those revivalist tent gatherings, full of enthusiasm, which have sometimes been exposed as frauds. Confession is often problematic for those who have never participated in it. The touching of the grotto wall, the statues and candles may seem quaintly devout. Outside the precincts of the shrine is the kitsch-commercial paraphernalia of images, candles and souvenirs.

The film's attention to detail will be appreciated by Catholics. It may not lead anyone in the audience, except the devout, to think that Lourdes is a place that they should visit. The sceptics in the audience will generally remain sceptical though they may appreciate better that authorities in Lourdes have procedures and doctors to examine those who think that they have been cured. The psychological benefit of religiously going to such a shrine will be appreciated – believers realising that this can be a personal healing experience in itself.

The screenplay shows a range of characters in the pilgrim group who illustrate these different perspectives: a mother who brings her disabled daughter every year to Lourdes and experiences a momentary improvement only, an old man who is lonely, several severely disabled patients, two gossiping and critical ladies... It is the same with the men and women volunteers with the Order of Malta: the men who are happy-go-lucky and glad to date the women assistants, the severely religious woman in charge who likes discipline and offers her own sufferings for others, the young volunteer who has not developed much compassion and eventually wishes she had gone on her skiing holiday as usual. Christine befriends the officer in charge who is attentive to her but fails her when he thinks she may not be cured.

A great strength of the film is the performance of Sylvie Testud as Christine. As an ill woman, confined to a wheelchair and completely dependent on others, she is both sweet and kind, extraordinarily patient despite her confessing to being angry. She is a woman of faith, joining in the hymns, prayers, visits to the grotto. However, she also wants to socialise, experience the pilgrimage as an outing. Her experience of healing is at first tentative, not immediately very spiritual, an entering into the ordinary, even banal, world of day-by-day. Is this a miracle? Not? Does she deserve this experience? Will it last - and does this matter? Does her experience challenge her deeply? Spiritually?

The priest with the group is down-to-earth (playing cards in the evenings and showing a sense of rhythm in dancing at the social at the end of the stay) but the lines he is given, inside and outside the confessional, tend to be the abstract sayings about God and freedom along with rather facilely quoting texts from the scriptures about completing the sufferings of Christ in our own bodies.

This may be the director's experience of priests but it seems quite a limited experience – a lot more, deeper sayings, could be put into the mouth of the priest or other characters which could offer more intellectually and spiritually satisfying leads and stimulations to understanding what faith, miracles and divine intervention are about. (The Canadian film, La Neuvaine (2005) by Bernard Ermond, set in the pilgrimage shrine of St Anne of Beaupre and raising questions about faith, simple and simplistic faith, rationalism and agnosticism, is a fine example of deeper reflection and how it can be incorporated into the screenplay of a film.)

ISSUES RAISED: GOD, FAITH, MIRACLES.

God

Almost all of the characters believe in God. The characters do not question God's existence. That questioning may be for many in the audience. What the characters do is express different aspects of belief.

One of the difficulties in discussions about God is God's seeming arbitrariness in dealing with suffering people. If God is God, why does God not intervene directly in the world and in people's lives (while we fail to remember how much most of us resent parents and authorities when they do intervene and take away our freedom and freedoms)? The other question is that of suffering – and one needs to reflect on Elie Wiesel's response when asked where was God in the holocaust. His answer suggests that God was in the ovens and with the suffering concentration camp victims.

Jessica Hausner has remarked that one effect of making Lourdes was to make her question more strongly the 'fairness' of God in dealing with different people, favouring some and not others.

Faith

There is an unfortunate presupposition amongst believers and non-believers alike that discussion of faith limits itself to the intellectual aspect of faith: believing what God says, intellectual assent to the truth. This keeps the discussion in the realm of the mind and focuses on ideas, reason and logic.

However, faith is something lived, lived in ordinary day-to-day life as well as in crises. It is what St Paul calls 'faith from the heart'. Faith is a spirituality in action, sometimes heroic, sometimes faint. This is dramatised in the characters in the film but, in the context of the Lourdes experience and people being prone to focus on faith and 'truth' in discussion, drawing attention to this more explicitly without being didactic would have enhanced the film and given more nuanced attention to the characters. The traces can be seen in Cecile, the Order of Malta leader, and her rather ascetical lived faith, and the old lady, pious and kind, who looks after Christine.

Miracles

In the early centuries of the church, miracles were claimed at the drop of a crutch, many of the reported miracles being enhanced storytelling. In the century of 'Enlightenment', the 18th century, Benedict XIV tightened criteria for the acceptance of a miracle. The language was used of an occurrence (generally a cure) being outside the laws of nature. More recent theological reflection highlights another criterion: that the cure take place as a response to and in the context of prayer. Maybe an occurrence is a psychosomatic experience but, in the context of faith and prayer, it can be described as 'miraculous', even though the 'big' miracles are those which seem to transcend the laws of nature.

Bringing this line of thought to what happens in the film, Lourdes, raises interesting issues of whose prayers are answered, whether Christine has experienced something miraculous ('big' or 'psychosomatic') and what is the nature of her spiritual experience – of the healing and its consequences for her life, of the challenge to her intellectual faith and to her faith from the heart, of her witnessing God's healing love and power?

There are some suggestions in the film – and Jessica Hausner does not want to make a propaganda film – but visitors to Lourdes have testified that they have experienced so much more of this faith from the heart which transcends previous experience.

Clearly, there can be a religious interpretation of the film as well as a secular interpretation (from SIGNIS award criteria to those for the Rationalist and Atheist Brian award). Believers will appreciate that this film is 'out there' in the world marketplace, a stimulus to discussion – and, maybe, an invitation to something more.

SIGNIS STATEMENT (Abbreviated)

14th September 2009

LOURDES

The new film, Lourdes, is a project written and directed by Austrian Jessica Hausner who has a Catholic background. However, she does not approach the subject from an explicit Catholic point of view. Rather, she wanted to put on the screen the Lourdes pilgrimage experience and to raise the issues of the nature of God, the possibility of miracles and the 'fairness' of God in granting healing to some and not to others.

The film-makers discussed the project with the bishop of Tarbes, where Lourdes is situated, and received collaboration during the making from the shrine authorities. It is certainly a film Catholics can be comfortable with, the presentation of devotion and faith, the range of perspectives of the pilgrims themselves, the experience of healings. The questions the film asks are those that believers and non-believers must ask.

The film shows a group of French pilgrims, with their chaplain and assistants from the Order of Malta, following the rituals of the visit to Lourdes: the grotto, the Eucharistic blessing, confession, processions, bathing in the water... The central character, Christine, has severe MS and is paralysed. She has come with some devotion but, principally, for a trip. The elderly lady she shares a room with is prayerful and solicitous for her. During the pilgrimage, Christine feels a growing strength and seems to be healed. There are various responses from the group, joy and suspicion, and the film is open-ended concerning Christine's future.

WHAT THE AUDIENCE SEES

Non- Catholics have been puzzled and some admiration for what they see. The gathering of the sick seems to some just like one of those revivalist tent gatherings, full of enthusiasm, which have sometimes been exposed as frauds. Confession is often problematic for those who have never participated in it. The touching of the grotto wall, the statues and candles may seem quaintly devout. Outside the precincts of the shrine is the kitsch-commercial paraphernalia of images, candles and souvenirs.

The film's attention to detail will be appreciated by Catholics. It may not lead anyone in the audience, except the devout, to think that Lourdes is a place that they should visit. The sceptics in the audience will generally remain sceptical though they may appreciate better that authorities in Lourdes have procedures and doctors to examine those who think that they have been cured. The psychological benefit of religiously going to such a shrine will be appreciated – believers realising that this can be a personal healing experience in itself.

The priest with the group is down-to-earth (playing cards in the evenings and showing a sense of rhythm in dancing at the social at the end of the stay) but the lines he is given, inside and outside the confessional, tend to be the abstract sayings about God and freedom along with rather facilely quoting texts from the scriptures about completing the sufferings of Christ in our own bodies.

A great strength of the film is the performance of Sylvie Testud as Christine. As an ill woman, confined to a wheelchair and completely dependent on others, she is both sweet and kind, extraordinarily patient despite her confessing to being angry. She is a woman of faith, joining in the hymns, prayers, visits to the grotto. However, she also wants to socialise, experience the pilgrimage as an outing. Her experience of healing is at first tentative, not immediately very spiritual, an entering into the ordinary, even banal, world of day-by-day. Is this a miracle? Not? Does she deserve this experience? Will it last - and does this matter? Does her experience challenge her deeply? Spiritually?

APPENDIX:

ISSUES RAISED: GOD, FAITH, MIRACLES.

God

Almost all of the characters believe in God. The characters do not question God's existence. That questioning may be for many in the audience. What the characters do is express different aspects of belief.

One of the difficulties in discussions about God is God's seeming arbitrariness in dealing with suffering people. If God is God, why does God not intervene directly in the world and in people's lives (while we fail to remember how much most of us resent parents and authorities when they do intervene and take away our freedom and freedoms)? The other question is that of suffering – and one needs to reflect on Elie Wiesel's response when asked where was God in the holocaust. His answer suggests that God was in the ovens and with the suffering concentration camp victims.

Jessica Hausner has remarked that one effect of making Lourdes was to make her question more strongly the 'fairness' of God in dealing with different people, favouring some and not others.

Faith

There is an unfortunate presupposition amongst believers and non-believers alike that discussion of faith limits itself to the intellectual aspect of faith: believing what God says, intellectual assent to the truth. This keeps the discussion in the realm of the mind and focuses on ideas, reason and logic.

However, faith is something lived, lived in ordinary day-to-day life as well as in crises. It is what St Paul calls 'faith from the heart'. Faith is a spirituality in action, sometimes heroic, sometimes faint. This is dramatised in the characters in the film but, in the context of the Lourdes experience and people being prone to focus on faith and 'truth' in discussion, drawing attention to this more explicitly without being didactic would have enhanced the film and given more nuanced attention to the characters. The traces can be seen in Cecile, the Order of Malta leader, and her rather ascetical lived faith, and the old lady, pious and kind, who looks after Christine.

Miracles

In the early centuries of the church, miracles were claimed at the drop of a crutch, many of the reported miracles being enhanced storytelling. In the century of 'Enlightenment', the 18th century, Benedict XIV tightened criteria for the acceptance of a miracle. The language was used of an occurrence (generally a cure) being outside the laws of nature. More recent theological reflection highlights another criterion: that the cure take place as a response to and in the context of prayer. Maybe an occurrence is a psychosomatic experience but, in the context of faith and prayer, it can be described as 'miraculous', even though the 'big' miracles are those which seem to transcend the laws of nature.

Bringing this line of thought to what happens in the film, Lourdes, raises interesting issues of whose prayers are answered, whether Christine has experienced something miraculous ('big' or 'psychosomatic') and what is the nature of her spiritual experience – of the healing and its consequences for her life, of the challenge to her intellectual faith and to her faith from the heart, of her witnessing God's healing love and power?

There are some suggestions in the film – and Jessica Hausner does not want to make a propaganda film – but visitors to Lourdes have testified that they have experienced so much more of this faith from the heart which transcends previous experience.

Published in Movie Reviews

Published in

Movie Reviews

Tagged under

Saturday, 18 September 2021 18:56

Sinner/ SIGNIS STATEMENT

SINNER

21st June 2007

Sinner is a small-budget, independent American film. Its topic is Catholic priesthood, specifically clerical celibacy. On this theme, it comes out positively for celibacy and ministry, though it illustrates the struggles and pitfalls.

The general public of 2007 may or may not be interested in priesthood. However, especially in the United States since 2002, much of the focus on priesthood, especially in the courts and in the media, has been on child abuse cases. This is acknowledged during the credit sequences of ‘Sinner’ with a voiceover collage concerning mostly well-known cases: Oliver O’ Grady, Boston, diocesan bankruptcies. Apart from these two minutes and the police chief character in the film who voices some of the public’s apprehensions about their children being altar servers and not becoming a statistic of abuse, pedophilia and abuse themes are absent from Sinner.

The film is of interest to Catholic audiences, especially to clergy. It might be seen as a case study as well as a Gospel allegory.

The screenplay was written by Steven Sills, who has a Catholic background, and directed by Marc Bernardout, who is British and Jewish, married to a Catholic.

Since the plot deals with a prostitute, Lil (Georgina Cates) who travels around parishes in what appears to be New England, seeking opportunities to compromise priests and blackmail them, it can be noted that there are a few provocative scenes and language which illustrate the character and the sometimes difficult situations for priests. There are some dramatic moments when the audience almost assumes that the priest will fall, only to find they have misjudged in anticipation. This is especially true of the last ten minutes of the film.

Perhaps it is more helpful to refer to the Gospel allegory first. This gives the framework for the plot with its plausibilities and some seeming implausibilities.

There are two priests in the parish of St Augustine (symbolic name with the film’s subject of sexuality and sin). The pastor, Fr Anthony Romano, played credibly by Nick Chinlund, is around fifty, an ordinary parish priest that many clergy will be able to identify with. However, the parish has become run down in terms of attendance at Masses and a younger man has been sent to assist and revive the parish, Fr Stephen (Michael E. Rodgers). He is what is sometimes called ‘a muscular Christian’ – and we initially see him jogging and, later, lifting weights. He is the earnest younger man, sometimes the bane of experienced pastors, with his rather rigid approach to life and morality, which he is not afraid of expressing bluntly. (Steven Sills’ plot synopsis in the Internet Movie Database refers to him as a ‘fundamentalist’ priest; he is not exactly ‘fundamentalist’ in the accepted sense, though he may appear so to an American audience where the word is more frequently used than elsewhere, in his unflinching dogmatic manner. Sills interestingly refers to the prostitute as a modern day Mary Magdalene which gives his interpretation of the very final scene that he wrote.)

When Lil, the prostitute, sets her sights on St Augustine’s, she attends Mass and listens to Fr Stephen’s reading of John 8, the story of the woman taken in adultery and the reactions of the religious leaders and of Jesus himself. She turns her attention to Fr Stephen since she has met the pastor and realises he is not an easy mark. Fr Stephen physically attacks her (‘to defend my celibacy’) and is arrested.

The rest of the film, which takes place over the next 24 hours, illustrates the hard-hearted attitude of the younger, righteous man who is aggressive, calls the police, upbraids his pastor and condemns him in rash judgments and wants to get rid of the prostitute. He represents those who assume that they should cast the first stone. The pastor, on the other hand, is compassionate, down-to-earth in his experience (we are given brief glimpses of his pastoral work), shrewd but willing to take risks, who, when he gives his car to Lil, explains to her the origins of the word, ‘redemption’, the buying back of someone.

Lil, over the brief time and her dealings with Fr Romano, trying to seduce, also trying to humiliate him, is eventually able to make some equivalents of ‘confession’ about her childhood, her profession and an abortion. Clearly, Fr Romano is doing what he thinks Jesus would have done.

To further comment on the plot would include what the bloggers call **spoilers** for those who have not seen the film. Suffice to say that there are many more strands in the character of the pastor, including some skeletons in his closet which have enabled him to commit himself to his celibacy. There is an unusual golf caddie companion (Brad Dourif) who brings some fantasy and overtones of angels and God to the character of the pastor. There is also the sub-plot with the police chief which is important at the end to show that the pastor is doing what Jesus did in the Gospels. The screenplay suggests that there might be more immediate redemption and awareness of redemption in the prostitute than in the zealous young priest.

The film has echoes of the British film, Priest, although the theme is quite different. It is also a reminder that there are a number of films which show priests and human weakness and repentance (thinking of Spencer Tracy in The Devil at 4 O’ Clock or, especially of Robert de Niro’s monsignor in True Confessions). In more recent times, there have been some films with positive portraits of priest as dedicated human beings, from the priest in Ken Loach’s Raining Stones to Edward Norton’s curate in Keeping the Faith.

Clergy might be interested in seeing Sinner as a starting point for discussions about contemporary priestly life.

Published in Movie Reviews

Published in

Movie Reviews

Tagged under

Saturday, 18 September 2021 18:56

Magdalene Sisters, The/ SIGNIS STATEMENT

THE MAGDALENE SISTERS

August 1st 2003

Scots actor director, Peter Mullan, has made an expertly- crafted but grim film about the Catholic Church in Ireland in the mid-60s. He has researched the laundries which were run by sisters who took in young women who had had children out of wedlock or who were considered wayward in sexual behaviour. Often they were called Magdalenes.

In recent years, in the English-speaking world especially, stories of physical and sexual abuse in Church parishes and institutions have surfaced with many priests and brothers facing civil courts and imprisonment. The Magdalene Sisters includes a priest character, the chaplain, whose behaviour reflects this kind of sexual abuse. Fewer sisters have been in court although many stories have been reported of physical cruelty rather than sexual abuse. Much of this cruelty took place during the 1950s and 1960s. The nun characters in this film were trained in the 1950s or earlier. The action takes place during the 1960s.

The film will certainly cause sadness in audiences who have been disturbed by the experiences of the 1990s, the revelations, the court cases and sentences. It will cause sadness for those who have positive memories of education by sisters and for those who want to see pleasant images of the Church and Church personnel. However, this story, which makes more impact perhaps because it is being seen rather than merely being read, is no less true than many of the recent stories that have been reported even in the Catholic press.

Is the film an attack on the Catholic Church? Peter Mullan says no. That was not his intention. It is a critique of a religious culture. Obviously it is an attack on and a critique of much of the harshness of the Church which has often been seen as characteristic of a stern Irish Catholicism. It is a critique of the abuse of power and authority in the name of the Church. (An apposite Gospel reference would be Matthew 20:24-28 with Jesus words on power, authority and service.) Mullan's comment is that Ireland was a theocracy. He has pointed out that in a theocracy, those who accepted this situation were prone to dominating behaviour in God's name. This means that the sisters themselves were victims of this religious-civil collaboration. While priests (as in the film) would make judgments about the young women who were to be sent to the laundries to keep them disciplined and under control, it was also the families who sent their daughters. The latter situation is seen in the film with the young woman who is raped by a cousin. She is either not believed or is blamed and is the innocent scapegoat for the wrong done by the man. At his Venice Festival press conference, Peter Mullan discussed other theocracies and the example was given of the Taliban - which led to some absurdly exaggerated press reports that he had likened the nuns in the film to Taliban leaders.

Although the film does not touch on it - except perhaps in the scene where a benefactor brings the first film to the convent (The Bells of St Mary's) and in the blessing of the new washing machines - this was the period of the Second Vatican Council and the call to rethink religious life and ministry. At what stage this reform was introduced in Ireland, those who remember can tell us, but it might have given some greater nuances to the characters and the behaviour in the film to make it even more compelling drama. One British press reviewer remarked that the film was a 'one-note' film with no variation on its grim storytelling.

However, this is the film that Mullan has made. The performances of the girls are first-rate. The nuns are less clearly drawn, mainly being seen in supervision sequences or in the refectory where their meal was more lavish than that of in the refectory where their meal was more lavish than that of the girls. It is Geraldine Mc Ewan's performance as the superior that demands attention. She has inherited a tradition of the Superior being strong, that her word is final and that she expresses God's will. She is shown to be cruel at times. Much as we might regret it, we can all probably remember religious who acted in this way. We might want to hurry to add that not all religious were like this. That is right. But, this film is a drama rather than a documentary. Most audiences will appreciate, as they would with a film criticising the police or politicians, that the majority of members of the profession did not act in this way.

The Magdalene Sisters can be seen as part of an honest examination of conscience by the Church and a request for repentance, an expression of sorrow and an apology, something which Pope John Paul II has exemplified and encouraged in recent years.

Published in Movie Reviews

Published in

Movie Reviews

Tagged under

Saturday, 18 September 2021 18:56

Lake of Fire/ SIGNIS STATEMENT

LAKE OF FIRE

November 22nd 2007

It is not every two and a half hour film, especially a documentary with black and white photography and many talking heads interviews, which can keep audience attention. Despite its length and the fact that it could have been further edited, Lake of Fire does.

On leaving the cinema, I found a video camera in my face, ‘What did you think of the film?’. Taken aback, I found I had said, ‘Good. Emotional. Mentally stimulating’. That still seems a just thumbnail review.

Basically, the film is about abortion and the complex moral issues that the changes in legislation in the last four decades and its repercussions have meant. There is plenty of material here, both intellectual and emotional, to provide solid bases for further discussion and dialogue.

British director Tony Kaye comes from the world of commercials and has the skills to communicate a great deal in thirty seconds or a minute. He also has the talent to tell stories within that space of time. Here he has a great number of minutes, so he packs his film with opinions, visual challenges and stories. It can be noted that he shot his film in the United States (and he was the photographer for his film). All the talking heads (except for Australia’s Peter Singer) are American as are the stories. Kaye began filming in 1993 and most of the footage comes from this period up to 1997 when he began work on the feature film, American History X, a powerfully alarming drama about modern American neo-Nazis with Edward Norton and Edward Furlong. He brings this great interest in fanatic fringe groups to Lake of Fire.

The changes in the legislation concerning abortion and the consequences for American sexual behaviour after the decision in the case Wade vs Roe have led to protests and demonstrations by both Pro- Life and Pro- Choice lobbies. These are the cinematically dramatic element in the film which explores the behaviour, motivation and determination of these groups. Since the Christian Pro- Life groups have been the most active and vociferous, it means that they get the most attention. There is a danger that even the most even-tempered audience will be so appalled by some of their strident behaviour that they will feel that the vociferous and often single-minded protests of the Pro- Choice lobby, who are not slack in confrontations and shouting of abuse, are models of sobriety compared with their opponents.

In this way the film is particularly American and becomes quite disturbing for a non-American audience. If we have read or seen television reports about the murders of doctors who carried out abortions in Florida, Georgia and Massachusetts and the almost rabid support of their followers in the name of God and Jesus, we might wonder who these people are. Kaye offers a great deal of footage, including interviews, as well as photos of the killings that can help explain but can also defy understanding let alone sympathy.

There is a scene of a police psychiatric interview with John Salvi in 1995 in Florida, a young man who seems clearly mad and who mouthes claims that what he is doing comes from what the Pope teaches, something he is really unable to explain rationally. Paul Hill, who had picketed clinics for months on end and who finished by killing three people, is interviewed during his protests, is seen during his trial and we hear his testimony that, as he is executed (in 2003), he is dying as a martyr for the protection of children. What is truly alarming is his language of execution (in God’s name). One of his followers is interviewed and finishes up by declaring that abortionists, sodomites (which in fact he does not understand) and children who say ‘goddammit’ during a sports match should be executed, the children for blasphemy.

A number of the speakers are religious ministers of Pentecostal churches and pray at their protests in charismatic style. A number of the ministers are rhetoric masters, able to stir crowds and control them – including by fierce radio ministry. A number of the ministers are also part of supremacist groups who advocate arms for all, including training little children with guns. The recurring thought for the ordinary Christian, embarrassed by this morally aberrant behaviour in support of moral principles, is how damning and wrong this is as the face of Christianity – as well as the important question about it all, ‘What would Jesus really think?’.

The amount of material Kaye has collected, the number of interviews with people he has conducted make Lake of Fire a strong documentary on fundamentalist Christians. And the title of his film comes from these Christians who readily relegate ‘sinners’ to an eternal, lava-like sea with people in it burning for eternity. Hell is a Lake of Fire.

This means that Lake of Fire is not just about abortion, not just about the fanatical and violent behaviour of fundamentalist Christians, it is about the nature of scripture and about the nature of God. Again, the discussions and the fanatical rants provide a great deal of varied material on a God who is by and large vengeful against sinners and those who do no follow his ‘law’ (an important factor). While Jesus is the personal saviour, he is not spoken about or prayed to in a personal, experiential way. He is the leader, the master.

Of great significance are the interviews with Norma Mc Corvey who used the name Jane Roe for the Roe vs Wade case. She speaks of her abortion, of the case, the consequences. She also relates how she was contacted by a Pro- Life campaigner, Flip Benham (a born again alcoholic and addict with a frightening grin), and invited to his centre where, after a time of welcome, she changed her attitude towards abortion and has become a campaigner and missioner against abortion.

And the word of God? Preacher after preacher, disciple after disciple, refers to the word of God as absolute, the absolute of absolutes, more than church and definitely more than conscience. But, the bible is read using random quotations without any reference to their context or any work to understand one saying in relation to another. Most of us realise that this is how literal reading of the bible becomes a cause leading to a crusade where so much of religious experience is channelled into apocalyptic fear and aggression.

Throughout this long film, there are a number of speakers. Of interest to Catholic viewers are sections with a woman who is Pro- Choice and a homily from Cardinal Roger Mahoney of Los Angeles. While there are many women, it is surprising in some ways how many men there are, many more than the women, who are eager to be heard on this issue. There are people in the street, politicians, doctors, religious personalities, writers, philosophers, lawyers. They have differing points of view but thoughtful audiences will appreciate the quieter moments when some of the speakers are calm and present rational reflections. These will differ from person to person in the audience. One of the best of the speakers is Noam Chomsky whose judicious considerations provide much food for thought even when one could take issue with his arguments. So does lawyer Alan Dershowitz as do a number of writers.

Somebody asked if the film was balanced, giving time without bias to each side of the debate. Is it skewed because of the presentation of the loud right without indicating some machinations of the left? Balance is something not achievable in this kind of film, equal time for all opinions. Rather, it gives a great deal of time to a range of opinions, some of them contradictory. But, while the protest scenes will probably confirm Pro- Life protestors in the audience in their stances, the discussion sections offer means for respectful listening to those with whom one disagrees which leads to fruitful debate as well as dialogue.

A challenge that the Pro- Choice demonstrators throw back to the Pro- Life protestors is how do they treat and care for the thousands of unwanted children today who find themselves in institutions and lacking the nurture and care of families. This is something that more temperate Christian groups do around the world rather than spend energy on the crusade.

But, films tell stories and Kaye has wisely left a story until the end. We follow a young women, 28 year old Stacy, who has decided to have an abortion as she goes into the clinic, the physical tests, the interview before the procedure with some questioning as to why she was choosing an abortion. We also go into surgery and see some detail of the abortion procedure itself, especially the emptying of the siphon tube with the parts of the foetus. In fact, earlier in the film, this has been shown in slightly longer sequences – Kaye has not shirked the physical realities of abortion.

Kaye makes this story, which comes to a moving end as the young woman reflects on what the experience has meant to her – and it is very affecting no matter what our moral stances on the issue, for or against. The film ends just rightly.

This storytelling is important otherwise this serious moral issue becomes just a matter of principle. But principles do not exist in the abstract. They are embodied in our behaviour and Lake of Fire offers us a film of principles which are not disembodied.

Published in Movie Reviews

Published in

Movie Reviews

Tagged under

Saturday, 18 September 2021 18:56

Religulous/ SIGNIS STATEMENT

RELIGULOUS

31st March 2009

As the title indicates, the filmmakers want us to approach this documentary on religion with a sense of the ridiculous.

For many believers, whatever the religion, this can be an interesting challenge. After all, everything human (even of divine origin) can be the subject of humour, otherwise it is made into an idol on a pedestal which can easily be knocked off. These believers will be interested to see how humorously aspects of religion are treated, with respect or stepping over bounds. For many believers, on the other hand, especially most of those displayed in this film (and it should be emphasised that most are displayed in images or paraded in interviews which make many of them really look and sound ridiculous and to be laughed at) will be upset at the criticism and ridiculing of their beliefs.

However, irrespective of good taste or stepping over bounds, anyone whose belief and beliefs are threatened by this kind of criticism does not really have well-grounded beliefs. And, after all, Religulous is only a film, a 100 minute movie.

The interviewer, Bill Maher, is well-known to American television audiences. He is a stand-up comedian become interviewer who has an agenda but who takes the trouble to find people that he does not agree with (especially in politics) and interviews them, sardonically but in a friendly way, usually, but is being provocative with the advantage over the interviewees, of course, of post-production editing his material – and also of placing captions at the bottom of the screen where he has evidence that the interviewee is not telling the truth or where he wants to make a joke. (He does this most effectively with some evangelists who rake in the money and who quote Jesus as fairly well-off, wearing fine linen and advocating being rich!).

Maher talks about his own background, half Jewish, half Catholic, brought up to age 13 as a Catholic, but whose creed is now questioning and doubt. Early in the film, he has an interview with his mother and sister questioning them about their religious beliefs and practice in the past. He admits up front that he finds many aspects of religions ridiculous and wants to illustrate this. As more than an aside, his director is Larry Charles who directed Borat (and Maher is a straightforward and polite interviewer compared with Borat!).

It is curious and interesting to note that in his film Maher stays with the Judaeo- Christian tradition and Islam and does not venture into the religions that originated in Asia.

Maher's agenda seems to be 1) the beliefs that seem to be rationally impossible and which are accepted blindly, 2) the relationship between faith and science and 3) the fundamentalist interpretation of scriptures whether the Hebrew Scriptures, the Christian Scriptures or the Koran.

One should note that for non-believers and for those who have not studied religion, Maher's parade can seem very funny as interviewees seem to be obstinately superstitious at best and obstinately stupid at worst. Actually, depending on where they stand, believers will think that those who believe in ways different from themselves are stupid – a case in point is listening to some former Mormons describe the mind-boggling claims of Joseph Smith and his visions or the Latin American Miami-based Jose Miranda who believes that he is Jesus incarnate at the Second Coming! - and Maher shrewdly points this out for his audience.

As regards beliefs which seem irrational:

It is easy to ridicule and to quote the scriptures to make a point seem religulous. To lump belief in a footprint of Jesus in Jerusalem, the Virginal conception of Jesus, the Virgin Birth, and beliefs about Mohammad's ascent into heaven and the 'talking snake' in the Garden of Eden is smart TV but not rationally honest. Any researcher will know that there are considerable differences in content and status of belief, between doctrine, religiosity and eccentric devotions. More nuanced questions need to be asked. It is interesting to note that Maher does not interview any professional theologian of any faith to clarify the meaning of the doctrinal or pious labels that he introduces into questions. He can toss off a statement about every Sunday drinking the blood of a man dead for 2000 years and does not offer an opportunity to anyone to say to him that he really doesn't know properly what he is talking about. His statement is irrational and needs substantial qualifications, the kind of rigour that he would demand of the people he is questioning.

As regards religion and science:

Maher interviews many fundamentalist American Christians as well as the manager of the Genesis Centre which is a theme park designed to illustrate creation in 6 days and deny any evolutionary theory. The adherents to an anti-evolutionary belief simply state that the word of God in Genesis has to be taken literally, so it is difficult to dialogue with them because the main discussion is not science but how to read and interpret the scriptures.

As regards Catholicism, it is something of a relief to hear Maher speaking with American Jesuit Fr George Coyne, Emeritus Director of the Vatican Observatory who points out, with the aid of a caption timeline, that the 2000 years or so of the creation of the Judaeo-Christian? scriptures were not the centuries of scientific research or language and so we cannot expect that to be found in the Scriptures. He also points out the long time gap from the Scriptures to the era of science and scientific research and language in more recent centuries. He highlights statements of John Paul II about the compatibility of Scripture and Evolution theory. In terms of the religulous, this puts the Catholic tradition, at least, in a different category from fundamentalists.

As regards the reading and interpretation of Hebrew, Christian and Muslim Scriptures:

Maher finds that the responses from many Christians, some Jews (and Rabbis) and Muslim scholars are grounded in a literal reading of their Scriptures. The Bible says, therefore... The Koran says, therefore...

It would be hoped that any fair-minded audience of Religulous, would realise that those who answer in this way are reading texts of past centuries as if they were written this morning with a 21st century mentality and vocabulary in mind – like the actor playing Jesus in the Florida Holy Land theme park who argues that God is a jealous God, taking jealousy in a contemporary sense which makes it sound petty rather than the meaning in the original language (which means beware of making arguments from translations without reference to the originals). Some of the Muslim commentators note that a Sura needs to be understood in its context and interpreted.

The main difficulty with Religulous and Bill Maher's approach is that he has not done his homework properly and is asking 'irrational' questions of some believers. The priest in St Peter's Square, Fr Reginald Foster, in his bluff and humorous way (which could scandalise some staunch believers), tries to tell Maher that he is out of date simply relying on basic and unnuanced Catechism answers he learned in Sunday school decades ago and not updating himself (as he would with changes in party politics policy) with recent and current developments and study. It is always surprising to find serious adults who are stuck in what St Paul reminds us: when I was a child, I thought like a child. They do not seem to realise that, as far as religion is concerned: now I am an adult, I should think and speak like an adult.

In an academic phrase, what is lacking in Maher's approach and his framing of questions, is that he does not have a sound and rational historiography. This means that he does not take into account changes in mindsets, language and ideas in expression through different cultures, languages and times. This makes him the equivalent of a fundamentalist in his own reading of some of the scriptures. The questions he asks and the statements he makes about, for instance, evidence for the existence of Jesus and likening the Gospels and their creation to modern-day biography or journalistic editing means that he did not take Fr Coyne's comments on eras of scripture and science on board: that there are substantial differences between Gospel portraits for evangelisation purposes in a media-limited era and contemporary biography accuracy (although all history – and documentaries – are not the truth 'as it is' but interpretation). Were Maher to research the material available (Jewish, Christian, Muslim) on interpretation, he would be asking different, better and more interesting questions.

Maher, as all of us should be (although many of his interviewees were devoutly locked into apocalyptic, rapture, end-times, second coming soon acceptance of wars and disasters), is concerned at the atrocities, the dehumanising features of history, so much of which comes from religious beliefs or causes. But ideology is not religion. For too many Christians, the religious identity is nothing more than a calling card or social status which requires some attendance at functions but really makes no demands on understanding faith or translating the message of the faith into justice or charity. Maher became disillusioned with religion, boring religion, early in his life. But, it was interesting that early in the film after an encounter, he thanked an interviewee for being Christ-like rather than Christian.

Now, there is a theme for another film: the spirituality of faith, lived faith, and the rationality of spirituality that is based on religious experience of the authentic kind.

Published in Movie Reviews

Published in

Movie Reviews

Tagged under

Saturday, 18 September 2021 18:56

X Files, The/ SIGNIS STATEMENT

THE X FILES: I WANT TO BELIEVE

2008

This is a ‘stand-alone’ film deriving from the extremely popular TV series which ran for nine years were simply a reasonably entertaining murder thriller with psychic overtones.

Needless to say (but still saying it), fans of the series will want to see this story no matter what. Whether they will be happy that, while Mulder and Scully (David Duchovny and Gillian Anderson) are centre-screen, this is not a film about FBI or government paranoia and mysterious aliens. It is a here-on-earth investigation of disappearances and a grim conspiracy that has to do with medical practice and malpractice.

Scully is now a doctor at a Catholic hospital and concerned about a young boy with a rare and deteriorating brain disease and whether he should be permitted to die or to undergo a number of radical and untested surgical procedures. Mulder, by contrast, is living, more or less, as a hermit. Scully is asked to bring him back for an FBI investigation which involves a former priest (Billy Connolly) who claims to have visions about the case. Mulder, with his keen intuitions about intuitions becomes interested. Scully is the rationalist, the sceptic. The FBI (Amanda Peet and Alvin ‘Xzibit’ Joiner) are on the side of the sceptics but keep getting drawn into the search for the missing women.

The surgery issue (and stem cell research) is intercut with the investigation, making the two issues closely connected in themes, especially about the efforts to prolong life. Mulder pursues the hunches and leads to a final confrontation. Scully has to question her presuppositions and the possibilities that there could be more realities than those that science allows. This centres on the truth or fakery of what psychics say and do. The film takes great interest in what advertising says is ‘supernatural’ (which it is not because that is the area of grace) but which, to be technical, is ‘preternatural’, experiences beyond the normal.

Set in a wintry West Virginia (though filmed in Canadian mountain locations), the film has action and chases but it also has a great deal of discussion about issues.

Scully works at a Catholic hospital where the Board is headed by Fr Ybarra (Adam Godley). The film makes him a very serious character and, from Scully’s point of view, quite unsympathetic, especially in discussing the decision about whether to go ahead with the boy’s surgery. This is dramatised in Scully’s discussions with Fr Ybarra, with the boy’s parents and their decision not to go ahead with the operations as well as in her impassioned speeches at the Board meeting where the hospital management support the decision against the surgery.

The screenplay introduces stem cell research since the surgery requires results from such research. In fact, the screenplay does not speak about stem cells from embryos or adult stem cells. And, in further fact, when the malpractice at the centre of the mystery and experimentation with dogs and with humans is exposed, the audience’s emotional response is against what is, as expected, characterised as the work of a ‘modern Dr Frankenstein’.

It can be added that nuns appear in the hospital but the producers have not checked out what contemporary nuns in hospitals actually do, whether they walk in solemn pairs down corridors or what they wear in terms of habits modified from older days – this presentation of nuns is over thirty years out of date.

Writer-director Chris Carter, who created the original series, says that his story ‘involves the difficulties in mediating faith and science’. This involves talk about belief in God or non-belief, Scully ‘cursing God’ for allowing children to be born with fatal diseases. Mulder, somewhat off-handedly but seriously, asks her whether she thinks God is unable to sleep because of this. Mulder is open to faith beyond the senses, at least. The title of the film, taken from a poster used in the series and shown here in his room, states in capital letters, ‘I WANT TO BELIEVE’.

Billy Connolly plays a former priest, Fr Joe, a convicted paedophile, with quite some restraint instead of his sometime over-the-top style, is a convicted paedophile priest, guilty of penetration of 37 of his altar boys.

Derogatory remarks are made about Fr Joe. Scully is particularly antagonistic and judgmental and Mulder makes a few of his offhand sardonic remarks about the priest. But the screenplay is actually leading its audiences into some more serious reflection on these issues and the consequences.

Fr Joe has been suspended from his priestly functions and lives in an institution for offenders. He experiences psychic ‘visions’, stating that he did not ask for them but that God had given them to him. It seems to be an opportunity for him to make some kind of atonement for what he has done. The question of what attitudes people should take towards offenders is a key one. By the end of the film, with some complications about the identity of the central criminal in terms of being one of Fr Joe’s victims – and some ‘mystical’ connections made between deaths and the saving of lives – this introduction of a paedophile priest is not a mere opportunistic device but something more substantial. It seems that underlying the character of Fr Joe in an X Files story we can find some of these deep issues.

Published in Movie Reviews

Published in

Movie Reviews

Tagged under

Saturday, 18 September 2021 18:56

Golden Compass, The/ SIGNIS STATEMENT

THE GOLDEN COMPASS

November 25th 2007

Peter Malone

In the ordinary course of events, film releases and film reviews, there would be little call for a statement on The Golden Compass. It is simply the most recent in a spate of fantasy films that have entertained wide audiences since 2001. The Lord of the Rings along with the first Harry Potter led the way that year, with Lord of the Rings sequels in 2002 and 2003. The Harry Potter films continue with the sixth to be released in 2008. Then came Narnia in 2005 (with Prince Caspian scheduled for 2008), the very pleasing The Bridge to Terabithia, followed by lesser fantasies, Eragon and The Dark is Rising. Now we have The Golden Compass. The principal films have noted, even celebrated authors: J.R.R. Tolkein, J.K.Rowling, C.S. Lewis and, now, Philip Pullman.

Actually, it is Philip Pullman who has led to the current controversies and many letters, website and email scaremongering about the film before its release.

But, first a comment on the film itself. This is a statement on the film and the film itself, not the novel ‘Northern Lights’ on which the film is based, or other Pullman novels - which I have not read. Some observations on Philip Pullman and his ideas will follow.

The Golden Compass is well-made, with a lot of intelligent dialogue, including the word ‘metaphysics’ a couple of times. Much of the film requires attention as well as some developed vocabulary. It looks very good: sets and design, effects for fantasy, and Nicole Kidman wearing a large array of costumes and gowns. The cast is strong with Dakota Blue Richards as the feisty (non-cute) heroine, Lyra, who, along with her daemon (more about that word later), Pan, who is the external version, the physical manifestation of her ‘soul’ with whom she can speak and argue, is ready to take on all comers – and does. The talented young actor, Freddie Highmore, is the voice of Pan.

The Golden Compass itself is a powerful mechanism that tells the truth and reveals what others wish to hide.

Apart from Nicole Kidman, who seems to be relishing the opportunity to be glamorous, charming and ruthlessly villainous, there is Daniel Craig as Lord Asriel, Sam Elliott, exactly as he is in the many Westerns he has appeared in, as Mr Scoresby and a long list of distinguished British stage and screen actors including Derek Jacobi, Christopher Lee, Claire Higgins, Tom Courteney, Jim Carter and the voices of Ian Mc Kellen (particularly strong and heroic) and Ian Mc Shane (villainous) as the rival bear kings. The film certainly has class. Interestingly (and perhaps surprisingly), writer-adapter and director is an American, Chris Weitz. After assisting his brother, Paul, with the directing of American Pie and the Chris Rock comedy, Down to Earth, they went to England to direct the film version of Nick Hornby’s About a Boy. Obviously, things English have appealed to him.

The plot offers, one might say, some variations on most of the fantasy films listed above. Afficionados will enjoy pointing out the comparisons. Yes, there is battle between good and evil – and in remote locations like the Rings Trilogy. Yes, there is a young central character, this time a girl, a kind of working class Hermione who lives in a college and has to do Harry Potter-like actions. The king bear, a literally towering figure, is reminiscent of Aslan in Narnia. There is a happy continuity in the imagination of all these films.

With a girl as central and with a number of battle sequences, the film should appeal to its boys and girls target audience – and the adults will probably enjoy it too (but may have to ask the children some clarifications of plot and characters).

There are some aspects of the film that may raise a religious eyebrow. The opening of the film speaks of parallel worlds, a feature of all of the best film fantasies. In our world, our souls are within us. In the parallel world, the soul is outside us, in the form of a symbolic animal called a ‘daemon’ (not a devil but a ‘spirit’ according to the origins of the word).

The other word is the ‘Magisterium’, the name of the all-powerful ruling body which is authoritarian and intent on eradicating free will so that all people, especially the children they abduct and experiment on, will lose their daemon and be completely conformist and happy. Science fiction has treated this plot in the several versions of The Invasion of the Body Snatchers. The Magisterium heads are embodied by Derek Jacobi and Christopher Lee who spurn tolerance and freedom and speak of heresy. Magisterium is, in fact, the word used for the authoritative teaching of the Catholic church, so that is clearly a critical element – though, as will be quoted later, Pullman says he is not anti-Catholic but anti-rigid and authoritarian religion.

The Golden Compass, normally, would be classified as PG or PG 13, suitable for most with a warning that there are some frightening scenes and battles for the younger audience.

However, the Catholic League For Religious and Civil Rights in the United States opened a campaign against the film three months before its release and published and widely distributed a booklet critical of the attitudes of the author and, by extension, his novels. It is called : ‘The Golden Compass: Agenda Unmasked’. The head of the League, William Donohue, has placed critical material on the League’s website and has been the guest on several American chat shows. His video except on his site was aired often in television news broadcasts at the time of the film’s premiere in countries like the UK. Reporting of the film on ordinary radio news bulletins generally referred to the Catholic League and its campaign. The League and Mr Donohue received enormous publicity.

A number of people in different parts of the world, scenting a controversy or a crusade, or simply out of displeasure at the alleged accusations, are involved in letter-writing, especially emails warning of the dangers of the film, and some personal denunciations.

As with all controversies and campaigns, attack without the benefit of viewing a film undermines the credibility of a crusade whether it is justified or not.