Join Us

LIFE STORY: Fr TED HARRIS MSC

What follows is a detailed article by Brian Davies, printed in the Sydney Catholic Weekly, 26th April, 2009. It gives information about the Japanese invasion of Papua New Guinea and the attack on Rabaul and its consequences for expatriates, especially the members of religious orders. The article also contains some biography of Ted Harris. It is published here with the permission of the editor of The Catholic Weekly.

The Japanese occupation of New Britain during World War II led to the greatest single loss of Australian life at sea when a Japanese ship, purportedly taking Australian POWs from Rabaul to Japan, the "Montevideo Maru", was torpedoed by a US submarine. But who and how many were on board the ship? No-one knows – a mystery. What was the fate and where are the remains of the man whose unforgettable heroism saved hundreds of lives, but not his own, the missionary priest, Fr Ted Harris MSC – another mystery. New Year 1941 was a watershed slipping into a tragedy, and was it only a coincidence that it was resolved on Easter Sunday?

Below the slopes of Tavurvur the active volcano, grumbling and frequently darkening the sky over Rabaul with steam and smoke, by April 1941 Australia had assembled a force about 1400-strong to defend the town and the mountainous island of New Britain against almost certain Japanese invasion.

It was possibly the most inadequate taskforce the AIF had mounted and soon to be, so swiftly, perhaps the least successful, although not without its heroes. Yet for more than 30 years after World War II the circumstances of the fall of Rabaul were not widely known, and still aren't.

The defending force comprised the 2/22nd battalion – a militia unit – of the AIF 23rd Brigade, a company of the New Guinea Volunteer Rifles and the 17th anti-tank battery, main weapons – two 6-inch artillery guns. Just before Christmas 1941 they were joined by six RAAF Wirraways, slow old-fashioned trainer planes and certainly no match for Japanese Zeros.

Most European women and children had left by ship or airlift, the last on a final DC-3 flight on December 28 1941, leaving behind about a 1000 Australian traders, teachers and public servants. To this day, their families have asked Australian governments to open wartime files about the decisions that were made then, to no avail. The "received wisdom" is that there are Cabinet documents in Canberra labelled "never to be released". This is the first of the mysteries associated with the fall of Rabaul.

There were as well on the island numerous Christian missions: among them Anglican, Lutheran, Methodist, Salvation Army and Catholic; these last, long-established, were manned by German Sacred Heart fathers, with six mission stations strung from Rabaul in the north to Gasmata, a modest seaport 300km south, as the crow flies, on the east coast. Between the two was an impenetrable mountain range, below which, halfway to Gasmata, was the MSC mission at Mal Mal in Jacquinot Bay, and 75km farther south another one at Awal.

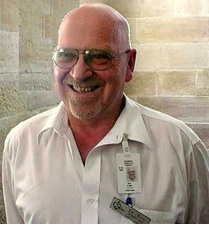

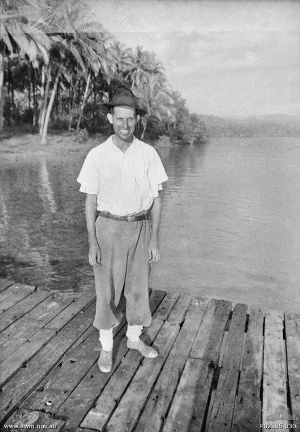

An Irish-Australian Balmain boy, Fr "Ted" Harris MSC was the priest at Mal Mal. He had more than 3000 Melanesian parishioners, a church – St Patrick's, a school, sports ground, a mission store and dispensary – and a two-roomed presbytery backing on to steep jungle.

He was well provisioned, had a launch, a shotgun for shooting game and a gramophone on which he played John McCormack records and other favourites like The Road to Gundagai.

Edward Harris was born in May 1905 in England to an Irish mother and Protestant English father, who converted because he wanted to share his family's passionate practice of Catholicism. They migrated to Australia; Ted learnt that in a family "sacrifice and love are twins". He was a Christian Brothers boy, dux of Balmain CBC's intermediate class 1920 and next year, turning 16, a NSW government junior public servant.

He and a workmate, another ex-Balmain CBC boy Frank Hidden, decided to study to matriculate and do Law. In November 1932, they graduated – Ted with second class honours and a prize in international law. Hidden went on to become a judge. Ted Harris, however, the day after graduation went straight to the Sacred Heart monastery at Douglas Park. He stayed, entered the novitiate in 1933, was professed in 1934 and ordained in 1939. To his vocation he brought spiritual aspirations, a mature mind, a compelling personality he had to tailor to community life and a deep conviction, as he wrote to his sister, that to be a worthy priest his only wish was "not to disappoint Our Lord".

"I came into religion to serve Him, draw closer to Him. If I do that I'll have everything; if I miss, the rest will be worth little," he said.

What else was in Ted Harris' "baggage"? He was a hiker and a bushwalker, Cox's River and the Megalong Valley were favourite spots for camping. He enjoyed sailing, followed boxing and enjoyed a bet at Harold Park on the greyhounds. He once gave his winning ticket to a mate who'd lost and was broke. In most respects he was a typical young Australian whose Irish connection lay in deliberately reproducing his mother's brogue, while he always said and wrote 'Twas and 'Tis and his one expletive exclamation was "Faith!"

But his fervour, his spiritual quest, his journey to God were dedicated and unswerving. Late in 1940, he was sent to the German Sacred Heart missionaries in Rabaul, secretary to Bishop Scharmach MSC. Six months later, the bishop approved his transfer to run St Patrick's mission, Mal Mal. Alone at Mal Mal, he was also teacher, doctor and nurse. It was June 1941.

On January 22, 1942, selected ships from a Japanese fleet of four aircraft carriers, battleships, cruisers and 16 destroyers entered Rabaul Harbour. At 2.30am on January 23 the first wave of 5000 Japanese marines landed. Australian orders of the day were that there would be no withdrawal.

The 2/22nd was a Victorian militia unit – 76 officers and 1400 other ranks – civilian clerks, tradesmen and others "called up" and trained; the battalion band was a Melbourne's Brunswick Salvation Army band*.

The invasion was preceded by three weeks of bombing and strafing. The Wirraways had taken off, shot down two Zeros, but made good their pilots' ultimate "resource" signalling "we who are about to die salute you". All died.

Opposing the landing 26 men died; 60 were wounded. The defence inadequacies were swiftly exposed, convincing the suspicious that "never to be released" Cabinet documents existed. Historian Dr Ian Downs wrote that the destruction of 2/22nd was regarded by government "as a misfortune that had to happen and internment of civilians a matter of course ... (in effect) hide the tragedy and no-one will know".

That day the most final of military action orders was issued: 'Every man for himself.'

Civilians came under brutal control. Fr McCullagh MSC and Br Brennan MSC were taken away and never seen again. Br Huth MSC was beaten near to death with a shovel; 44 other priests and brothers were jammed into the upper floor of a convent building and confined. Native nuns were subjected to ridicule and worse. Native Catholics and other Christian islanders were killed. Bishop Sharmach and his close community were kept under "house arrest". Several hundred men were POWs; more would follow.

Meanwhile, lost to the outside world, the surviving 2/22nd's ordeal began. There was no communication with Australia and hardly any within the island. Fr Harris had no certain idea Rabaul had fallen until the first survivors landed on his doorstep at Mal Mal, a month later.

The survivors hoped to reach Gasmata for a boat or rescue to Port Moresby. To get there however they had to cross the Baining Ranges – 50km of trackless jungle, towering mountains, deep gorges and crocodile-infested rivers – on short rations. In the "wet" it rained almost ceaselessly. Once past Malingi, they would reach the coast.

They would discover Fr Harris at Mal Mal – a figure in old trousers, sandshoes, a white shirt and black priest's hat – as they stumbled towards him. Starting out, rested and cared for, from the Sacred Heart mission at Baining where the ranges began, the crossing had taken nearly three weeks. Like the clothes they wore, they were torn and ripped, too, boots gone, some with sores and ulcers, hungry and exhausted.

Fr Harris cared for them: two hours washing and dressing their wounds, a square meal, sweets and the gramophone playing, some fresh clothes, stretchers to sleep on, breakfast, food packs to take with them, upriver by canoe and then a 50km walk to reach Fr Culhane, an Irish MSC, at Awal.

The next party arrived at Mal Mal with distressing news: A Japanese ship combing the coast for escapers had spotted about 180 men on the beach at Tol plantation in Wide Bay, north of Mal Mal. The men surrendered to a landing party. Their hands were then lashed behind them and each was bayoneted and shot to death. A few survivors were with the escaping party. Fr Harris's coolness and good spirits calmed over-strung nerves and revived morale, but the Japanese were obviously close.

As it left for Awal, this second party advised him that there were probably about another 50 soldiers struggling south.

Happy to leave things to God, Fr Harris resumed life at Mal Mal and its outlying villages, nine and 12km away: medical and nursing rounds, conducting marriages, baptisms, funerals and celebrating Mass at St Patrick's.

The third party to arrive, under Lt Best, estimated there were only 20 stragglers to come. Best was relatively fit and determined to reach Port Moresby. Fr Harris gave him his launch, all his petrol and enough food for the party for three weeks.

No sooner had Best left, than another party walked in, fairly fit. Fr Harris over-nighted them with the usual care and provisioned them for the row upriver to the walking track to Awal. They urged him to escape with them, reminding him of the Tol massacre. He declined.

On the track, moments of perception, of capture and punishment – death ... the stress of flight ... the unforeseeable ... a future as dark as a tomb – a pall along the escape routes, a dreadful companion when the men were at rest. But Fr Ted Harris's cheerfulness would dispel gloom and lift spirits. The next party to reach him,however, brought grim news.

Gasmata was occupied by the Japanese and 200 escapers heading there would soon reach Mal Mal.

With 200 men who now could not go any further, Fr Harris split them into two camps at nearby Drina and Wunung, some of the sick to be cared for at St Patrick's. With a plantation family, the Yenckes, cooking at Wunung and himself catering for Drina, he and the men's officers were running a makeshift army camp. Men were posted to keep watch for the Japanese or, best, a rescue ship. Food was rationed and some of the men were assigned to expand a native garden, but the almost unmanageable problems were malaria, the injured, the sick and the exhausted. Fr Harris was running out of quinine and other medicines. He was to bury nearly 30 of the men at St Patrick's, including, some who claimed to be Catholics so they would receive a Christian burial. He assured the men all could count on that, Catholics or not. A crowded "ecumenical" congregation regularly heard Mass.

The officers – Major Owen, Major Palmer the medical officer, Captain Goodman and Lieutenant David Selby – and Fr Harris established close bonds. Their commitment was to their men, fiercely so, and in Fr Harris they found a man they came to respect and admire. If they were rescued they planned to kidnap him to take him to safety. Waiting, tensions rose. Fr Harris brought the Yenckes and another plantation family in to live in the presbytery. He moved into the school room. Rescue was the only escape.

A slender hope was the possibility that Lt Best might have reached Port Moresby. They weren't to know that Fr Culhane at Awal had also given his launch away for the same purpose. (Fr Culhane MSC was subsequently "tried" and shot dead for helping escapers.)

Good Friday, 1942, fell on April 3. Captain Goodman, a Protestant, went to Fr Harris and said the men wanted him to deliver a Good Friday address, which he did, according to David Selby, a deeply moving one.

Two days later the men were in St Patrick's at Easter Sunday Mass.

The liturgy was interrupted at the back of the church. Two neatly uniformed, heavily armed Australian soldiers called several worshippers out to tell them they were rescued. Lt Best and others had made it. The newcomers had travelled in a launch from Port Moresby to tell them that in three days time the Laurabada would tie up to take them all off.

Gallantry and endurance were needed to get the sick and injured from Drina and Wanung to Mal Mal – some men died doing it; but Fr Harris made one thing clear: he wouldn't be going with them ... he would not leave his parish and his parishioners.

All made their farewells. David Selby later wrote "as we pulled out in a blinding rainstorm he was a spare figure standing on the shore waving, still wearing his smile."

There are conflicting and gruesome versions of where and how Fr Harris died.

It's agreed the Japanese took him away from Mal Mal. The only certainty after that is his execution.

The final mystery in the Fall of Rabaul surrounds the Montevideo Maru. The Japanese claimed that when the ship was torpedoed in 1942 it was carrying all the prisoners of war and civilians taken when they invaded New Britain. But who was on the ship?

The Montevideo Maru Search group says the claim was to conceal war crimes like the Tol murders and massacres at other sites, for which there is evidence, and that there are scores of victims whose last resting places are as unknown as Fr Ted's.

LIFE STORY: FR ROY O'NEILL MSC

Catholic Communications, Sydney Archdiocese,12 Nov 2009

Religion is good medicine. Over the past decade, studies have confirmed spirituality and faith have measurable health benefits and not only promote healing after illness or accidents, but increase longevity. In the US, Duke University's Centre for the Study of Religion, Spirituality and Health, scientists have found that people with an active religious life have spiritual resources that can help them break cycles of addiction, recover from depression and spend less time in hospital. According to latest research, patients who are committed to their faith and involved with their religious communities, are not only mentally and frequently physically healthier than their non-believing counterparts, but also have lower blood pressure, fewer deaths from heart disease and other stress related illnesses.

While such findings may come as a surprise to many, for Fr Roy O'Neill, the Catholic Chaplain at Sydney's sprawling hospital's complex at Randwick NSW they are simply confirmation of what he and the Church have long known. Religious belief contributes to physical, emotional and mental well-being, and is a significant factor in promoting healing.

"There is now a stack of evidence from scientists and researchers worldwide on the positive benefits of spiritual and pastoral care. It doesn't matter whether the patient is a card-carrying Catholic or an Anglican, Buddhist, Muslim or from some other religion. If his or her spiritual needs are met, there is a beneficial effect on the protocol of healing," Fr Roy says.

The positive impact of religion on patients is something Fr Roy has seen first-hand during his 10 years as Chaplain at the Randwick Hospital Complex which includes the Prince of Wales Hospital, both public and private, the Royal Hospital for Women, the Sydney Children's Hospital, and the Euroa and Kiloh Centres which provide psychiatric care.

In addition to his work as a Chaplain at the hospitals where Catholic patients number 250 across the Campus on any one day, Fr Roy has written at length about the power of faith and spirituality and their significance in helping patients heal as part of thesis for his Master of Ministry degree, entitled "Moments of Grace and Blessing: Rites and Rituals in the Process of Healing."

Being a Chaplain is an Extraordinary Gift. However, the friendly, down-to-earth, good-humoured, Queenslander, admits that when he was first ordained, he never expected to work in a hospital.

"But while I may not have chosen to become a hospital chaplain, my 10 years at Randwick have been in one sense the most rewarding – a loaded word but I can't think of another word to explain how I feel - and the most touching ministry I have ever been involved with. At times the work can be heartbreaking and is always highly emotionally charged, but against the tragedy and sadness there is the joy of someone making it against all odds or of babies being born and new life created."

Fr Roy also believes a hospital Chaplain is particularly privileged. "It is an extraordinary gift to be invited to be with people at the most sacred moments of life, whether entering or leaving life. It is a wonderfully trusting position to be in - to have people trust you at the happy times of their lives as well as the critical times."

He becomes impatient, however, with the popular misconception that a priests' primary function as a hospital Chaplain is to administer "Last Rites" to the dying. Not only is "Last Rites" a misnomer, a term not so much used now by the Church or Catholics, but a hospital Chaplain's role is far more broad and, as stated earlier, an integral part of the healing process.

At the Randwick Hospital Campus, the Catholic Chaplaincy comprises Fr Roy and Sister Ann Duncan of the Sisters of St Joseph of the Sacred Heart, and is backed up by two parish priests from the nearby Our Lady of the Sacred Heart Church, Randwick who are also part-time chaplains at the Campus and can step in when needed. Priests at the parishes of Rosebery, Coogee and Maroubra Beach are also on call. But the main work is carried out by Fr Roy who celebrates a Mass for staff, patients and families at noon every Wednesday in the hospital complex' small chapel, as well as celebrating a 3 pm Mass there on the first, third and any fifth Sunday each month.

A Chapel for All Faiths

"As well as Sister Ann and myself there are two Anglican Chaplains, a Salvation Army chaplain, a Jewish Rabbi, several Muslim Chaplins, a Presbyterian chaplain, a Uniting Church Chaplain and two Buddhist Chaplains and we all share the chapel," says Fr Roy who dismisses the controversy earlier this year over Crucifixes and other Christian symbols having to be stored between services as nothing more than a "media created beat-up."

"The chapel at Randwick was built six years ago after the previous one in the old P.O.W. huts at the back of the Campus burned down. Both the new and old chapels which date back more than 20 years have always been multi-faith and for the new chapel, all of us from the various different chaplaincies got together to raise the money to have it built."

According to Fr Roy as with the previous chapel, each group of specific religious symbols is kept in cupboards within the chapel and brought out when needed whether it is a Jewish Menora, the Koran and compass showing the direction of Mecca or the Chalice and Crucifixes of the Catholic faith.

Each day after arriving at the Hospitals' Campus around 7.00 am, Fr Roy checks the lists of patients and noting any recent admissions who have nominated themselves as Catholic, and begins his visits of the various wards to speak with new arrivals as well as those who been in hospital for several days, weeks or even months. These visits also include talking with families and one ward he is particularly close to C2West which is the cancer ward at the Sydney Children's Hospital.

Ministering to children battling terminal illnesses might seem grim but for Fr Roy both the children and their families fill him with inspiration and humility. "This is where you meet the human spirit at its most amazing," he says. "The children and their families are just outstanding people and from a spiritual aspect you really do see God's presence in the midst of suffering." He pauses for a moment. "It's hard to put into words but possibly the best way to describe this is to use a slogan that was once for a vocations centre: "God only knows what work a priest does."

He smiles then adds: "One of the nicest things about this work is that often having tried to assist and support people through tragedies or critical times, they frequently contact me later to ask if I'll celebrate a marriage or a baptism or some other joyous family occasions."

Religious Instruction by Correspondence

Growing up on a sugarcane farm in Finch Hatton in Northern Queensland, 73 km west of Mackay, Fr Roy was the youngest of three children by 13 years and grew up with his cousins for playmates rather than siblings. But in a rare occurrence, his cousins were closer than most. His father's younger brother had married his mother's younger sister. "So I had double cousins and they lived next door," he laughs.

His father was Catholic and his mother, formerly a Congregationalist converted to the Catholic faith on marriage. "My parents were religious in the right sense of the word," Fr Roy says. "We went to Mass on Sundays and they were always conscious of the social needs of the community, not just of Catholics but everyone. From them I learned tolerance. Dad was also Chairman of the local council."

But it was his parents' generous giving hearts he remembers most and he treasures the remark from a local who approached him in middle age after his mother had died to tell him how kind she'd been to him, and the meals she had given him as a young cane cutter. "If it hadn't been for your mother, I'd have been in gaol a long time ago," he told Fr Roy.

As a child, Fr Roy attended a tiny primary school in Pinnacle where he received his first-ever formal religious instruction by correspondence with Sister Mary Loyola who was based in Rockhampton. "She was a Sister of Mercy and well ahead of her time, organising religious education by correspondence for kids in State schools along the lines of Distance education," he says. "Our Parish Priest, Fr Hayes from our parish of Francis de Sales was also a major influence on me as a child and I clearly remember him teaching myself and several other sons of cane farmers, the responses to the Latin Mass, sitting under the house of one of our neighbours!"

For his secondary education, Fr Roy became a boarder at Downlands College, Toowoomba, which was run by the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart. "I am not sure how or exactly when I decided my vocation was to be a priest. It was a gradual realisation and probably began in childhood," he says.

Latin a Prerequisite to Train as a Priest

On leaving school, Fr Roy was keen to enter the seminary but first he needed to do senior Latin. "It was 1963 and in those days Latin was a requirement and you couldn't get into a Seminary without it." Finally, Latin and other subjects under his belt, Fr Roy began his training to become a priest with the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart. During his Apostolic year he taught at Monivae College in Hamilton, Victoria and discovered he loved teaching. Ordained on May 24 1975 he returned to West Victoria to teach as the school' senior English master and in 1982 found himself back at his old school, Downlands College, but this time as one of the Senior Boarding Masters. "The kids used to wonder how I knew where to catch them smoking!" he grins.

By 1986, however, Fr Roy finally fulfilled his dream working in an overseas mission at Hagita High School in Milne Bay, Papua New Guinea. But within a short time he was back in Australia and principal of Downland College. His next role was as Vocations Director at the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart in Sydney then in 1997 he took a Sabbatical Year to Ireland before taking up a position in Fiji where the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart were building a Seminary. Then in 2000, he was appointed as Hospital Chaplain at the Randwick Campus.

"What is most important for a hospital chaplain is his compassion and humanity," he says. "Some people who may turn to him for comfort and help may not have been closely associated with the Church for many years and you need to connect with them in a way they feel comfortable. It is very much a ministerial role in a hospital setting and a necessary skill is the ability to just be with people, wherever they may be on their faith journey, and to work out how best to meet their spiritual needs. Doctrine and dogma take a backseat to compassion and understanding."

THE TUNNELS OF FORTRESS RABAUL

By Tyson Doneley, M.S.C.

From Annals Australia, October 1985

|

Father Tyson Doneley, M.S.C., former Rector of Chevalier College, Bowral, N.S.W., St John's College, Darwin, and now on New Britain as Rector of St Peter Chanel Seminary writes for Annals readers about the famous Rabaul Tunnels. These tunnels were dug by the Japanese, and by local people, as well as by Indians and Chinese captured at Singapore who are buried in the cemetery at Bitapaka outside Rabaul. |

RABAUL, on its magnificent reef-free harbour, is situated in East New Britain, PNG, just south of the equator. That word Rabaul conjures up visions of volcanoes, earthquakes, Japanese - and rightly so.

PNG has over 20 active volcanoes - smoking islands like Manam or Karkar, growling giants like Kilenge's Langla in West New Britain, superbly scenic like twin peaked Balbi in North Bougainville, or with a single eruption like Ulawun (the Father) 20 miles West of Rabaul; and Rabaul itself is cradled in a nest of volcanoes - its magnificent harbour the caldera of a giant volcano sea-swamped, with secondary vents producing the Mother, the North Daughter, the South Daughter, Rabalan akeia, the still-active Matupit and, most recent of all, Vulcan, which emerged from the harbour and blew its top off in 1937. And a new disturbance is threatening Rabaul again with land rising near Matupit.

Then, for earthquakes Rabaul is in one of the most earthquake-prone areas of the world. This is Ples Guria or the Earthquake (guria) Place. How eerie it is to feel this solid, solid earth moving and shaking like a trampoline under foot! In March this year we had a shake of intensity 7.6 on the Richter scale of nearly 5 minute's duration. The epicentre was 200 kms to the east, and fortunately the disturbance was some 40 kms down, or very great damage would have resulted. Little gurias, a tremble, a start, a lurch, are frequent, and provide alternative talking points to VFL results or cricket or politics.

But one other happening has left its mark on Rabaul: a human happening, the Japanese occupation in World War II. Rabaul was chosen by the Japanese to be their pivot in the S.E. Pacific because of its splendid harbour, its airfields and its strategical importance for thrusts to the mid-Pacific or south to Australia or west to Port Moresby. Overnight on January 22nd-23rd, 1942, a mighty Japanese armada slid into Simpson Harbour and Blanche Bay. Australia's token force, the 2/22nd, Lark Force, fought gallantly, especially at Vulcan Beach near Malagunan base camp, then took to the hills and jungle, which proved to be almost as hostile as the Japanese. However, many defeated both jungle and Japanese to escape from the north coast towards Talasea or the south coast towards MalMal (those who escaped the Tol Plantation Massacre).

At this stage, the war was all Japan's: Singapore fell and all the East. Rabaul was built up as Fortress Rabaul, and 100,000 air, military and naval men were poured into it. It was the springboard and supply base for the Solomons, especially Guadalcanal where 24,000 Japanese fell. From Rabaul sallied forth the invasion fleet for Port Moresby that was turned back in the battle of the Coral Sea, and so formidable were the Rabaul defences that the Allies never tried to assault it by land. Even today the beaches of the Gazelle peninsula are lined with concrete blockhouses and backed by lines of trenches and gun emplacements.

Rabaul, looking from the Coast Watchers' memorial. |

But as the war turned against Japan, Rabaul came under attack from the air more and more. Waves of U.S., Australian and N.Z. fighters and bombers firstly wiped out the Japanese air force, then began to pound Rabaul remorselessly day in, day out. 20,500 tons of bombs are estimated to have been dropped on Rabaul - more than on Berlin, it is said. Not a building stood, not even a vehicle could stir on the ground in daytime as Allied planes prowled overhead. It is estimated that the Japanese lost 2,000 planes in PNG (to the Allies' l,000) and remnants are scattered everywhere. 200 yards off Matupit airstrip, in the jungle, sit a Zero, a medium bomber and a giant twin engined bomber. Just off Matupit Island and the South Daughter volcano and Tokau plantation near Kokopo, whole planes are just below the surface of the water. Scraps of planes - wings, fuselage, propellers, engine parts - litter Rapopo plantation where Ulapia minor seminary stands. Even today live bombs are turning up; in 1982 a truckload of "old" bombs was found in the grounds of Rabaul's National Broadcasting Commission and dumped at Matupit - and soon began to explode in dump fires, and caused the closure of the nearby airport for several days.

Yet from this lethal rain of bombs, the Japanese stepped forth almost unharmed (though they themselves were contained, cut off from giving or receiving aid - 89,000 troops, 57,000 military, 32,000 naval, were here at the surrender, - frustrated by Atlied strategy). They survived by an almost incredible system of tunnels - hospitals were in tunnels, machinery was in tunnels, storehouses were in tunnels, barges were in tunnels, H.Q. were in tunnels, troops were in tunnels: short U-turn air raid tunnels, long winding tunnels, many-storeyed tunnels (at Malagunan they are at four levels in the hills): all adding up to a total of 55O to 800 kms of tunnel, claimed to be longer than the famous catacombs of Rome.

Some are concrete lined, some were supported with palm trunks, others are hewn from the pumice and coral. Some today have fallen in because of the gurias, many are filled with thousands of bats and bat dung; some have ancient ammunition that no one wants to handle; one by the main road near Vulcan has five supply barges stored in line; most have been swept clean of what they held; occasional ones are found as they were left at war's end. At least one was blown up with the Japanese still inside it, refusing to emerge to surrender. Years before the Japanese, the Germans had built a tunnel through the hills to the north coasT it was later dug out into an open road but was known as Tunnel Hill road. Gaping Japanese tunnels on Tunnel Hill road were the HQ of the dreaded Kempeitai, the secret police. Here Peter To Rot was questioned, the brave Tolai catechist who was put to death by the Japanese for continuing doggedly in catechist's work that they forbade. He was imprisoned in another tunnel system at Rakunai, a few miles from Rabaul, then put to death apparently by an injection administered by two doctors.

A single Jig tree near Rabaul, with the Author. |

The hills and cliffs around Rabaul lent themselves to tunneling. Close to Tavuilu near Vulcan were several naval hospitals. One of these consisted of large shafts driven through a mountainside with l6 connecting shafts: these were the wards and here the patients lay in semi-darkness, with light supplied by wicks burning in coconut holders containing coconut oil, held in wire brackets on the wall. There was also electricity but as fuel grew scarce or generators failed, the coconut oil was the fall back. The metal wall spikes and smoke-marked walls are there still, along with the niches in the walls that acted as places to store personal belongings. There was also a machine for helping to circulate air through the tunnels and make conditions a little better for the sick men held there.

Nearby is a second naval hospital, and it has an interesting story. One of our Japanese missionaries asked us to host a Japanese university lecturer, Sam Nagara, who wished to visit the naval hospital tunnels where his uncle surgeon Captain Tetsuya Hatona, now dead, had been in charge during the war. Sam had been a small boy of eleven years in Hiroshima when the bomb fell in 1945. But he had been pressed into digging tunnels for the defence of Japan and had been ill.

"Don't go to school today, son" his mother had said - "you are not well enough." He stayed home, and that very day his school and friends were destroyed by the atomic bomb. After the war he won a scholarship to Hawaii, married an American Japanese girl and lives in Ann Arbor, Michigan, lecturing at the University of Michigan.

We had no idea of the whereabouts of his uncle's hospital tunnels, but his uncle had written a book called "Cave Hospital" about his life in Rabaul with the 8th Naval Hospital unit. In it he had a few snapshots and several maps that he had smuggled out in his belt at the surrender, and local students were able to identify the tunnels from the maps. Everything was now wildly overgrown and most of the tunnel area at this point had fallen in or been blown up, but one giant tree drawn on the map by Captain Hatona was there still, above a main tunnel entrance, only it was forty years later. We found a few relics to send back to Sam's aunt, a roof spike for a lamp from a cement-lined administration room, a few nails, and we took a number of photographs to send her also.

Later, when Capt. Hatona's book was translated, it made interesting reading: it told of the departure from Kure in November 1943 for the South Seas, the early confidence, the meeting with tropical diseases dengue, malaria, dysentery; the gradual turning of the tide of war; the decision to put the hospital into tunnels in the hills in May 1944, the increasing tempo of the bombing, the dwindling of food supplies and the efforts to grow sweet potatoes, beans and tapioca and make potato wine, and soap from coconut oil (even the surgeon spent much of his time working in the gardens, which were sometimes raided by other hungry units); there is his growing depression and foreboding as the war got worse and worse, then it was all over after Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Here is the entry for July l5th, 1945:

8.l0am. Formations of medium bombers and bombing. In the middle of the native village above the tunnels, more than twenty 25Olb bombs were dropped. The hospital patients' bus received a direct hit and one truck was destroyed. Apart from this, Yokohachi Special Unit's Truck was damaged but fortunately no-one was hurt. However, the native village has become unrecognizable. The native huts were all partially or completely destroyed. About 17 dead were brought out, after being buried alive in air raid shelters etc. Mothers were digging in the ground, children were crying - it was really pathetic. I thought of the pitiful situations in the bombing at home (in Japan).

The evening meal celebrated the Lantern Festival, and when rice cakes covered with bean jelly were put out, all the soldiers were very happy. When the bombing broke off, a fairweather moon could be seen shining over the coconuts as they swayed in the breeze.

It was not possible to live completely in the tunnels, so small out-houses, shelters, cookhouses, "factories" were built outside for conviviality and work in order to escape from tunnel life.

Japanese submarine base. Rabaul. |

This fashion also was followed by the missionaries in the prison camp at Ramale valley 8 kms into the hills near Vunapope. Here some 350 fathers, brothers, sisters and local people were kept 18 months through the worst bombings of l944 and 1945 when the main mission station at Vunapope, Japanese occupied, was completely destroyed. The old tunnels at Ramale still remain, with their ten entrances. Water is feet deep in some of them. The outside huts have long since perished; but down in the valley still runs the cold sweet unfailing water that made life possible in this jungle camp.

Close to Vunapope at Ulagunan is a correspondence school for secondary students, Holy Spirit School. One morning in 1979 a student went down to the creek to work and to his amazement he saw a man whom he thought was a Japanese. He ran back in fright to get other students. The grouP came back and the man was still there: but when the group came, he turned and ran into the maze of tunnels honeycombing the area. The boys told their story (one was a student later at Chanel seminary) and traces were found in the tunnels where several people had been living but no-one was found even though a TV crew came from Japan and messages were cried out with loudspeakers in JaPanese. Peraps it was no Japanese at all; however, there were memories of the soldiers who had long refused to surrender but gave up at last in Guam and the Philippines. But here the tunnels still hold their secret, kilometres of tunnel on several levels, with many entrances, an elaborate concreted main entrance; and the sole inhabitants today are thousands of bats who swish or squeak by, leaving only the draught from their flight and the flutter of beating wings.

In many places today the tunnel entrances are blocked by soil or timber to prevent piccaninies wandering into them and becoming lost or encountering tunnel bats and snakes; though an occasional strong guria opens up old entrances; and their stories are being forgotten, or can only be conjectured as at Submarine Bay near Rabaul where deep tunnels in the coral cliffs and the remains of a small mobile crane corroborate the story that this was where submarines were vicutalled; if attacked, batteries of guns in the cliff tunnels above would protect them or they would sink into the depths where the shelf of rock dropped a sheer 600 feet.

Perhaps a later age will search for tunnel relics and history. In the 198O's the Japanese Naval Radio Base was discovered in a tunnel behind Rabaul. In 1980 one keen searcher found a sealed tunnel with a staff car well preserved in it, and another one with spare aeroplane parts. The tide of history has rolled on but the flotsam and jetsam of war and time still make Rabaul an intensely interesting place as well as one of the most beautiful areas in all PNG.

From "ANNALS AUSTRALASIA" October 1985

FATHER John Leary MSC who died on January 19 2009 and was buried at Wadeye [Port Keats] in the Northern Territory, spent almost all his priestly life working among aboriginal communities on Bathurst Island, Wadeye, the Daly River and around Darwin. In the coming months, as to a tribute to this much loved missionary priest, Annals will re-publish a selection from among the many articles that he contributed over the years that he lived and worked in the Territory. May he rest in Peace. |

TOMMY Mungulung was the police tracker at Daly River in Australia's Northern Territory when the MSC Mission began. As the small aboriginal community grew in numbers, Tommy joined them to become the hunter to supply meat in the form of wallaby or kangaroo and, in season, ducks and geese.

In a group of expert hunters Tommy was supreme. His reading of tracks was instantaneous and unerring. Returning from Darwin with me in a jeep, as we sped along, Tommy drew my attention to human tracks on the road, 'one man, two women, three children, not far ahead!' he announced. Sure enough, some minutes later we caught up with the group whose tracks Tommy had seen earlier so clearly on the bitumen.

Shortly after there were fresh buffalo tracks. 'He's running: said Tommy excitedly and, a little later, 'he's slowing down, he's walking, he's close up'. There was the buffalo around the next corner.

Emu on the menu

On another occasion an emu raced across the road in front of the jeep and into the bush. 'Stop, Father!' commanded Tommy as he jumped from the jeep, pulling from his head a large red and white spotted handkerchief, waving it wildly to the accompaniment of dancing and loud whistling. The emu, now some three hundred metres or so into the bush, promptly stopped and slowly retraced its steps to investigate the handkerchief, the whistling and the dancing. When it arrived within a few metres of the jeep Tommy reached for his shotgun with one hand while continuing to wave the handkerchief with the other. And so one emu was added to the menu that evening.

While walking with Tommy, until I knew better, I would often excitedly draw attention to many possum scratches on the bark of a tree. Just one quick look and Tommy would declare no possum at home. The most recent tracks were downwards, indicating, of course, that the possum had left the tree.

Two feller one bullet

It was the same with an array of tracks around a goanna hole. The last of them were outward bound. 'He's out hunting, Tommy would say with a smile. When Tommy became enthusiastic about such tracks a possum or a goanna was added to the menu.

When it came to hunting kangaroo, Tommy would assess how many were needed. Should it be four, Tommy would take four .303 bullets. Invariably he returned with four kangaroos. On one occasion he took four bullets and returned with five kangaroos. 'How come five, Tommy? I asked. 'I bin line `em up two feller with one bullet, explained Tommy. Tommy used infinite care and patience to position himself to snare his game. He would fade imperceptibly and silently into the bush background, becoming a part of it.

Duck or geese on a billabong would appear undisturbed by the slow approach of a patch of water-lillies shrouding Tommy's head and shotgun. Taken completely by surprise, there was always a maximum number of ducks or geese per cartridge. Leaving the dead birds floating, Tommy would quickly secure those only slightly wounded, and ready to take off, by wringing their necks. Others that had fluttered off wounded into surrounding scrub were carefully noted and later retrieved.

Aboriginal 'roads'

I well recall the days of the great flood in 1957 when the waters were receding from the airstrip. Magpie geese were everywhere. Tommy was out on the strip with his shotgun. Wounded geese were falling out of reach into deep water. He called on the services of three women to swim and retrieve the geese. I protested to Tommy about leaving the difficult work to the women and not doing it himself. 'Too dangerous, too many crocodiles!' Tommy replied honestly and with some traditional chauvinism. His gallantry was not equal to his hunting ability.

Each year, at the proper time, Tommy would take off to attend a ceremony at Timber Creek on the Victorian River.

Dressed in a loincloth, with a bundle of spears in hand for hunting on the way, he would follow the ancient 'blackfellow roads' used for thousands of years by his ancestors. I first became aware of these roads after they were pointed out to me by my aboriginal travelling companions on a walk from Port Keats to Daly River. They were narrow tracks no more than a foot wide, cleared and hardened over the centuries by the tramp of feet intent on trade or ceremony.

The memory of Tommy the hunter, Tommy the ceremony man, raised worrying questions in my mind when I returned to Daly River twenty years later. Tommy, still active, no longer practised his hunting; no longer gathered his spears or walked the traditional roads to Timber Creek.

No need for traditional skills

Young men had lost a model and a teacher. They, like Tommy, were caught up in a new system that was subtly replacing the need to exercise those intricate skills that made them the most self-reliant and independent of all peoples.

A cash economy, based in great part on social security payments and a local store, had replaced the need to hunt. Vehicles had replaced the need to walk and all those good traditional things that went with a simple thing like walking.

My concern was not so much with the loss of hunting and walking, but with the speed and nature of the change. It gave no time for authentic cultural growth and became destructive of basic cultural values. So it tended to strip people like Tommy of their independence, their dignity, their sense of responsibility, their self-assurance and, in fact, opened the way to many harmful consequences.

Pressures of White culture About this time there was a young man at Port Keats, Claude Narjic, son of a leading traditional man, who was deeply concerned about the destructive effects the many pressures from the dominant white culture were having on him and his people. Late one night he knocked on my door. He simply wanted to speak of his anxiety, his feelings of helplessness in a situation where there appeared to be no answers, where all his past, even his identity was threatened. The one-sided conversation continued all night.

Slowly, carefully

When I was invited on one occasion to a Government-sponsored meeting in Adelaide on aboriginal policy I asked Claude to accompany me. Claude addressed the meeting. He began by recalling that there was a word in his language very important to this occasion; it summed up all he wanted to say. The world was `thawait'. It had a double significance, namely 'carefully, and 'slowly' He spoke of the confusion and the damage done to his people by the pressures and expectations of the dominant culture. He gave examples and after each example added `thawait, thawait'. Aboriginal people, he said, before the coming of the white man, for hundreds of years, did not have to hurry with change. They absorbed the small demands of change slowly. They had time to become comfortable with it and make it their own. However, when the white man's culture arrived, so powerful and so very different from their own, demanding quick adjustments, they were completely exposed and totally unprepared. So, please, when you are dealing with us, he pleaded, let it be done carefully and slowly. The thing that hurts us most is when white people develop condemnatory attitudes by failing to understand us and the past that has made us. `Thawait, thawait, thawait!'

Leaving the 'old way'

Another prophetic figure at Port Keats at this time was Harry Pallada. After Harry received his first wage packet he became worried and called a community meeting. He saw the wage packet as representing a new way of living and as a challenge to the old. 'My old way of living,' he said, 'is part of me - living in the bush and from the bush, being secure and at home there, teaching my children to do the same. What if I leave the old way which is me and try to live this new way which is not me? I know I will end up makadu.' `Makadu' means literally a 'non-person', a 'nobody'.

Both Claude and Harry realised to some degree, the great distance between their traditional way of living and that of the dominant white culture about them; and the immense risks and difficulties involved in trying to make up the distance. They also know that many non-Aboriginal Australians are succumbing to the pressures generated within their own culture, and would want to demand with Claude - `thawait, thawait, thawait'.

From "Annals Australasia" January/February 2009