MSC life stories

LIFE STORY: Fr TED HARRIS MSC

What follows is a detailed article by Brian Davies, printed in the Sydney Catholic Weekly, 26th April, 2009. It gives information about the Japanese invasion of Papua New Guinea and the attack on Rabaul and its consequences for expatriates, especially the members of religious orders. The article also contains some biography of Ted Harris. It is published here with the permission of the editor of The Catholic Weekly.

The Japanese occupation of New Britain during World War II led to the greatest single loss of Australian life at sea when a Japanese ship, purportedly taking Australian POWs from Rabaul to Japan, the "Montevideo Maru", was torpedoed by a US submarine. But who and how many were on board the ship? No-one knows – a mystery. What was the fate and where are the remains of the man whose unforgettable heroism saved hundreds of lives, but not his own, the missionary priest, Fr Ted Harris MSC – another mystery. New Year 1941 was a watershed slipping into a tragedy, and was it only a coincidence that it was resolved on Easter Sunday?

Below the slopes of Tavurvur the active volcano, grumbling and frequently darkening the sky over Rabaul with steam and smoke, by April 1941 Australia had assembled a force about 1400-strong to defend the town and the mountainous island of New Britain against almost certain Japanese invasion.

It was possibly the most inadequate taskforce the AIF had mounted and soon to be, so swiftly, perhaps the least successful, although not without its heroes. Yet for more than 30 years after World War II the circumstances of the fall of Rabaul were not widely known, and still aren't.

The defending force comprised the 2/22nd battalion – a militia unit – of the AIF 23rd Brigade, a company of the New Guinea Volunteer Rifles and the 17th anti-tank battery, main weapons – two 6-inch artillery guns. Just before Christmas 1941 they were joined by six RAAF Wirraways, slow old-fashioned trainer planes and certainly no match for Japanese Zeros.

Most European women and children had left by ship or airlift, the last on a final DC-3 flight on December 28 1941, leaving behind about a 1000 Australian traders, teachers and public servants. To this day, their families have asked Australian governments to open wartime files about the decisions that were made then, to no avail. The "received wisdom" is that there are Cabinet documents in Canberra labelled "never to be released". This is the first of the mysteries associated with the fall of Rabaul.

There were as well on the island numerous Christian missions: among them Anglican, Lutheran, Methodist, Salvation Army and Catholic; these last, long-established, were manned by German Sacred Heart fathers, with six mission stations strung from Rabaul in the north to Gasmata, a modest seaport 300km south, as the crow flies, on the east coast. Between the two was an impenetrable mountain range, below which, halfway to Gasmata, was the MSC mission at Mal Mal in Jacquinot Bay, and 75km farther south another one at Awal.

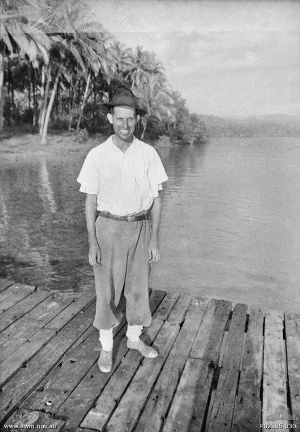

An Irish-Australian Balmain boy, Fr "Ted" Harris MSC was the priest at Mal Mal. He had more than 3000 Melanesian parishioners, a church – St Patrick's, a school, sports ground, a mission store and dispensary – and a two-roomed presbytery backing on to steep jungle.

He was well provisioned, had a launch, a shotgun for shooting game and a gramophone on which he played John McCormack records and other favourites like The Road to Gundagai.

Edward Harris was born in May 1905 in England to an Irish mother and Protestant English father, who converted because he wanted to share his family's passionate practice of Catholicism. They migrated to Australia; Ted learnt that in a family "sacrifice and love are twins". He was a Christian Brothers boy, dux of Balmain CBC's intermediate class 1920 and next year, turning 16, a NSW government junior public servant.

He and a workmate, another ex-Balmain CBC boy Frank Hidden, decided to study to matriculate and do Law. In November 1932, they graduated – Ted with second class honours and a prize in international law. Hidden went on to become a judge. Ted Harris, however, the day after graduation went straight to the Sacred Heart monastery at Douglas Park. He stayed, entered the novitiate in 1933, was professed in 1934 and ordained in 1939. To his vocation he brought spiritual aspirations, a mature mind, a compelling personality he had to tailor to community life and a deep conviction, as he wrote to his sister, that to be a worthy priest his only wish was "not to disappoint Our Lord".

"I came into religion to serve Him, draw closer to Him. If I do that I'll have everything; if I miss, the rest will be worth little," he said.

What else was in Ted Harris' "baggage"? He was a hiker and a bushwalker, Cox's River and the Megalong Valley were favourite spots for camping. He enjoyed sailing, followed boxing and enjoyed a bet at Harold Park on the greyhounds. He once gave his winning ticket to a mate who'd lost and was broke. In most respects he was a typical young Australian whose Irish connection lay in deliberately reproducing his mother's brogue, while he always said and wrote 'Twas and 'Tis and his one expletive exclamation was "Faith!"

But his fervour, his spiritual quest, his journey to God were dedicated and unswerving. Late in 1940, he was sent to the German Sacred Heart missionaries in Rabaul, secretary to Bishop Scharmach MSC. Six months later, the bishop approved his transfer to run St Patrick's mission, Mal Mal. Alone at Mal Mal, he was also teacher, doctor and nurse. It was June 1941.

On January 22, 1942, selected ships from a Japanese fleet of four aircraft carriers, battleships, cruisers and 16 destroyers entered Rabaul Harbour. At 2.30am on January 23 the first wave of 5000 Japanese marines landed. Australian orders of the day were that there would be no withdrawal.

The 2/22nd was a Victorian militia unit – 76 officers and 1400 other ranks – civilian clerks, tradesmen and others "called up" and trained; the battalion band was a Melbourne's Brunswick Salvation Army band*.

The invasion was preceded by three weeks of bombing and strafing. The Wirraways had taken off, shot down two Zeros, but made good their pilots' ultimate "resource" signalling "we who are about to die salute you". All died.

Opposing the landing 26 men died; 60 were wounded. The defence inadequacies were swiftly exposed, convincing the suspicious that "never to be released" Cabinet documents existed. Historian Dr Ian Downs wrote that the destruction of 2/22nd was regarded by government "as a misfortune that had to happen and internment of civilians a matter of course ... (in effect) hide the tragedy and no-one will know".

That day the most final of military action orders was issued: 'Every man for himself.'

Civilians came under brutal control. Fr McCullagh MSC and Br Brennan MSC were taken away and never seen again. Br Huth MSC was beaten near to death with a shovel; 44 other priests and brothers were jammed into the upper floor of a convent building and confined. Native nuns were subjected to ridicule and worse. Native Catholics and other Christian islanders were killed. Bishop Sharmach and his close community were kept under "house arrest". Several hundred men were POWs; more would follow.

Meanwhile, lost to the outside world, the surviving 2/22nd's ordeal began. There was no communication with Australia and hardly any within the island. Fr Harris had no certain idea Rabaul had fallen until the first survivors landed on his doorstep at Mal Mal, a month later.

The survivors hoped to reach Gasmata for a boat or rescue to Port Moresby. To get there however they had to cross the Baining Ranges – 50km of trackless jungle, towering mountains, deep gorges and crocodile-infested rivers – on short rations. In the "wet" it rained almost ceaselessly. Once past Malingi, they would reach the coast.

They would discover Fr Harris at Mal Mal – a figure in old trousers, sandshoes, a white shirt and black priest's hat – as they stumbled towards him. Starting out, rested and cared for, from the Sacred Heart mission at Baining where the ranges began, the crossing had taken nearly three weeks. Like the clothes they wore, they were torn and ripped, too, boots gone, some with sores and ulcers, hungry and exhausted.

Fr Harris cared for them: two hours washing and dressing their wounds, a square meal, sweets and the gramophone playing, some fresh clothes, stretchers to sleep on, breakfast, food packs to take with them, upriver by canoe and then a 50km walk to reach Fr Culhane, an Irish MSC, at Awal.

The next party arrived at Mal Mal with distressing news: A Japanese ship combing the coast for escapers had spotted about 180 men on the beach at Tol plantation in Wide Bay, north of Mal Mal. The men surrendered to a landing party. Their hands were then lashed behind them and each was bayoneted and shot to death. A few survivors were with the escaping party. Fr Harris's coolness and good spirits calmed over-strung nerves and revived morale, but the Japanese were obviously close.

As it left for Awal, this second party advised him that there were probably about another 50 soldiers struggling south.

Happy to leave things to God, Fr Harris resumed life at Mal Mal and its outlying villages, nine and 12km away: medical and nursing rounds, conducting marriages, baptisms, funerals and celebrating Mass at St Patrick's.

The third party to arrive, under Lt Best, estimated there were only 20 stragglers to come. Best was relatively fit and determined to reach Port Moresby. Fr Harris gave him his launch, all his petrol and enough food for the party for three weeks.

No sooner had Best left, than another party walked in, fairly fit. Fr Harris over-nighted them with the usual care and provisioned them for the row upriver to the walking track to Awal. They urged him to escape with them, reminding him of the Tol massacre. He declined.

On the track, moments of perception, of capture and punishment – death ... the stress of flight ... the unforeseeable ... a future as dark as a tomb – a pall along the escape routes, a dreadful companion when the men were at rest. But Fr Ted Harris's cheerfulness would dispel gloom and lift spirits. The next party to reach him,however, brought grim news.

Gasmata was occupied by the Japanese and 200 escapers heading there would soon reach Mal Mal.

With 200 men who now could not go any further, Fr Harris split them into two camps at nearby Drina and Wunung, some of the sick to be cared for at St Patrick's. With a plantation family, the Yenckes, cooking at Wunung and himself catering for Drina, he and the men's officers were running a makeshift army camp. Men were posted to keep watch for the Japanese or, best, a rescue ship. Food was rationed and some of the men were assigned to expand a native garden, but the almost unmanageable problems were malaria, the injured, the sick and the exhausted. Fr Harris was running out of quinine and other medicines. He was to bury nearly 30 of the men at St Patrick's, including, some who claimed to be Catholics so they would receive a Christian burial. He assured the men all could count on that, Catholics or not. A crowded "ecumenical" congregation regularly heard Mass.

The officers – Major Owen, Major Palmer the medical officer, Captain Goodman and Lieutenant David Selby – and Fr Harris established close bonds. Their commitment was to their men, fiercely so, and in Fr Harris they found a man they came to respect and admire. If they were rescued they planned to kidnap him to take him to safety. Waiting, tensions rose. Fr Harris brought the Yenckes and another plantation family in to live in the presbytery. He moved into the school room. Rescue was the only escape.

A slender hope was the possibility that Lt Best might have reached Port Moresby. They weren't to know that Fr Culhane at Awal had also given his launch away for the same purpose. (Fr Culhane MSC was subsequently "tried" and shot dead for helping escapers.)

Good Friday, 1942, fell on April 3. Captain Goodman, a Protestant, went to Fr Harris and said the men wanted him to deliver a Good Friday address, which he did, according to David Selby, a deeply moving one.

Two days later the men were in St Patrick's at Easter Sunday Mass.

The liturgy was interrupted at the back of the church. Two neatly uniformed, heavily armed Australian soldiers called several worshippers out to tell them they were rescued. Lt Best and others had made it. The newcomers had travelled in a launch from Port Moresby to tell them that in three days time the Laurabada would tie up to take them all off.

Gallantry and endurance were needed to get the sick and injured from Drina and Wanung to Mal Mal – some men died doing it; but Fr Harris made one thing clear: he wouldn't be going with them ... he would not leave his parish and his parishioners.

All made their farewells. David Selby later wrote "as we pulled out in a blinding rainstorm he was a spare figure standing on the shore waving, still wearing his smile."

There are conflicting and gruesome versions of where and how Fr Harris died.

It's agreed the Japanese took him away from Mal Mal. The only certainty after that is his execution.

The final mystery in the Fall of Rabaul surrounds the Montevideo Maru. The Japanese claimed that when the ship was torpedoed in 1942 it was carrying all the prisoners of war and civilians taken when they invaded New Britain. But who was on the ship?

The Montevideo Maru Search group says the claim was to conceal war crimes like the Tol murders and massacres at other sites, for which there is evidence, and that there are scores of victims whose last resting places are as unknown as Fr Ted's.

LIFE STORY: FR ROY O'NEILL MSC

Catholic Communications, Sydney Archdiocese,12 Nov 2009

Religion is good medicine. Over the past decade, studies have confirmed spirituality and faith have measurable health benefits and not only promote healing after illness or accidents, but increase longevity. In the US, Duke University's Centre for the Study of Religion, Spirituality and Health, scientists have found that people with an active religious life have spiritual resources that can help them break cycles of addiction, recover from depression and spend less time in hospital. According to latest research, patients who are committed to their faith and involved with their religious communities, are not only mentally and frequently physically healthier than their non-believing counterparts, but also have lower blood pressure, fewer deaths from heart disease and other stress related illnesses.

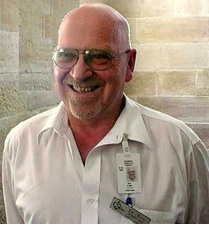

While such findings may come as a surprise to many, for Fr Roy O'Neill, the Catholic Chaplain at Sydney's sprawling hospital's complex at Randwick NSW they are simply confirmation of what he and the Church have long known. Religious belief contributes to physical, emotional and mental well-being, and is a significant factor in promoting healing.

"There is now a stack of evidence from scientists and researchers worldwide on the positive benefits of spiritual and pastoral care. It doesn't matter whether the patient is a card-carrying Catholic or an Anglican, Buddhist, Muslim or from some other religion. If his or her spiritual needs are met, there is a beneficial effect on the protocol of healing," Fr Roy says.

The positive impact of religion on patients is something Fr Roy has seen first-hand during his 10 years as Chaplain at the Randwick Hospital Complex which includes the Prince of Wales Hospital, both public and private, the Royal Hospital for Women, the Sydney Children's Hospital, and the Euroa and Kiloh Centres which provide psychiatric care.

In addition to his work as a Chaplain at the hospitals where Catholic patients number 250 across the Campus on any one day, Fr Roy has written at length about the power of faith and spirituality and their significance in helping patients heal as part of thesis for his Master of Ministry degree, entitled "Moments of Grace and Blessing: Rites and Rituals in the Process of Healing."

Being a Chaplain is an Extraordinary Gift. However, the friendly, down-to-earth, good-humoured, Queenslander, admits that when he was first ordained, he never expected to work in a hospital.

"But while I may not have chosen to become a hospital chaplain, my 10 years at Randwick have been in one sense the most rewarding – a loaded word but I can't think of another word to explain how I feel - and the most touching ministry I have ever been involved with. At times the work can be heartbreaking and is always highly emotionally charged, but against the tragedy and sadness there is the joy of someone making it against all odds or of babies being born and new life created."

Fr Roy also believes a hospital Chaplain is particularly privileged. "It is an extraordinary gift to be invited to be with people at the most sacred moments of life, whether entering or leaving life. It is a wonderfully trusting position to be in - to have people trust you at the happy times of their lives as well as the critical times."

He becomes impatient, however, with the popular misconception that a priests' primary function as a hospital Chaplain is to administer "Last Rites" to the dying. Not only is "Last Rites" a misnomer, a term not so much used now by the Church or Catholics, but a hospital Chaplain's role is far more broad and, as stated earlier, an integral part of the healing process.

At the Randwick Hospital Campus, the Catholic Chaplaincy comprises Fr Roy and Sister Ann Duncan of the Sisters of St Joseph of the Sacred Heart, and is backed up by two parish priests from the nearby Our Lady of the Sacred Heart Church, Randwick who are also part-time chaplains at the Campus and can step in when needed. Priests at the parishes of Rosebery, Coogee and Maroubra Beach are also on call. But the main work is carried out by Fr Roy who celebrates a Mass for staff, patients and families at noon every Wednesday in the hospital complex' small chapel, as well as celebrating a 3 pm Mass there on the first, third and any fifth Sunday each month.

A Chapel for All Faiths

"As well as Sister Ann and myself there are two Anglican Chaplains, a Salvation Army chaplain, a Jewish Rabbi, several Muslim Chaplins, a Presbyterian chaplain, a Uniting Church Chaplain and two Buddhist Chaplains and we all share the chapel," says Fr Roy who dismisses the controversy earlier this year over Crucifixes and other Christian symbols having to be stored between services as nothing more than a "media created beat-up."

"The chapel at Randwick was built six years ago after the previous one in the old P.O.W. huts at the back of the Campus burned down. Both the new and old chapels which date back more than 20 years have always been multi-faith and for the new chapel, all of us from the various different chaplaincies got together to raise the money to have it built."

According to Fr Roy as with the previous chapel, each group of specific religious symbols is kept in cupboards within the chapel and brought out when needed whether it is a Jewish Menora, the Koran and compass showing the direction of Mecca or the Chalice and Crucifixes of the Catholic faith.

Each day after arriving at the Hospitals' Campus around 7.00 am, Fr Roy checks the lists of patients and noting any recent admissions who have nominated themselves as Catholic, and begins his visits of the various wards to speak with new arrivals as well as those who been in hospital for several days, weeks or even months. These visits also include talking with families and one ward he is particularly close to C2West which is the cancer ward at the Sydney Children's Hospital.

Ministering to children battling terminal illnesses might seem grim but for Fr Roy both the children and their families fill him with inspiration and humility. "This is where you meet the human spirit at its most amazing," he says. "The children and their families are just outstanding people and from a spiritual aspect you really do see God's presence in the midst of suffering." He pauses for a moment. "It's hard to put into words but possibly the best way to describe this is to use a slogan that was once for a vocations centre: "God only knows what work a priest does."

He smiles then adds: "One of the nicest things about this work is that often having tried to assist and support people through tragedies or critical times, they frequently contact me later to ask if I'll celebrate a marriage or a baptism or some other joyous family occasions."

Religious Instruction by Correspondence

Growing up on a sugarcane farm in Finch Hatton in Northern Queensland, 73 km west of Mackay, Fr Roy was the youngest of three children by 13 years and grew up with his cousins for playmates rather than siblings. But in a rare occurrence, his cousins were closer than most. His father's younger brother had married his mother's younger sister. "So I had double cousins and they lived next door," he laughs.

His father was Catholic and his mother, formerly a Congregationalist converted to the Catholic faith on marriage. "My parents were religious in the right sense of the word," Fr Roy says. "We went to Mass on Sundays and they were always conscious of the social needs of the community, not just of Catholics but everyone. From them I learned tolerance. Dad was also Chairman of the local council."

But it was his parents' generous giving hearts he remembers most and he treasures the remark from a local who approached him in middle age after his mother had died to tell him how kind she'd been to him, and the meals she had given him as a young cane cutter. "If it hadn't been for your mother, I'd have been in gaol a long time ago," he told Fr Roy.

As a child, Fr Roy attended a tiny primary school in Pinnacle where he received his first-ever formal religious instruction by correspondence with Sister Mary Loyola who was based in Rockhampton. "She was a Sister of Mercy and well ahead of her time, organising religious education by correspondence for kids in State schools along the lines of Distance education," he says. "Our Parish Priest, Fr Hayes from our parish of Francis de Sales was also a major influence on me as a child and I clearly remember him teaching myself and several other sons of cane farmers, the responses to the Latin Mass, sitting under the house of one of our neighbours!"

For his secondary education, Fr Roy became a boarder at Downlands College, Toowoomba, which was run by the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart. "I am not sure how or exactly when I decided my vocation was to be a priest. It was a gradual realisation and probably began in childhood," he says.

Latin a Prerequisite to Train as a Priest

On leaving school, Fr Roy was keen to enter the seminary but first he needed to do senior Latin. "It was 1963 and in those days Latin was a requirement and you couldn't get into a Seminary without it." Finally, Latin and other subjects under his belt, Fr Roy began his training to become a priest with the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart. During his Apostolic year he taught at Monivae College in Hamilton, Victoria and discovered he loved teaching. Ordained on May 24 1975 he returned to West Victoria to teach as the school' senior English master and in 1982 found himself back at his old school, Downlands College, but this time as one of the Senior Boarding Masters. "The kids used to wonder how I knew where to catch them smoking!" he grins.

By 1986, however, Fr Roy finally fulfilled his dream working in an overseas mission at Hagita High School in Milne Bay, Papua New Guinea. But within a short time he was back in Australia and principal of Downland College. His next role was as Vocations Director at the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart in Sydney then in 1997 he took a Sabbatical Year to Ireland before taking up a position in Fiji where the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart were building a Seminary. Then in 2000, he was appointed as Hospital Chaplain at the Randwick Campus.

"What is most important for a hospital chaplain is his compassion and humanity," he says. "Some people who may turn to him for comfort and help may not have been closely associated with the Church for many years and you need to connect with them in a way they feel comfortable. It is very much a ministerial role in a hospital setting and a necessary skill is the ability to just be with people, wherever they may be on their faith journey, and to work out how best to meet their spiritual needs. Doctrine and dogma take a backseat to compassion and understanding."